How Cincinnati Is Punching Above Its Weight in the Climate Fight

For years this midsize city has been a leader in cutting carbon pollution. Now it’s raising its game with solar, energy efficiency, and electric cars.

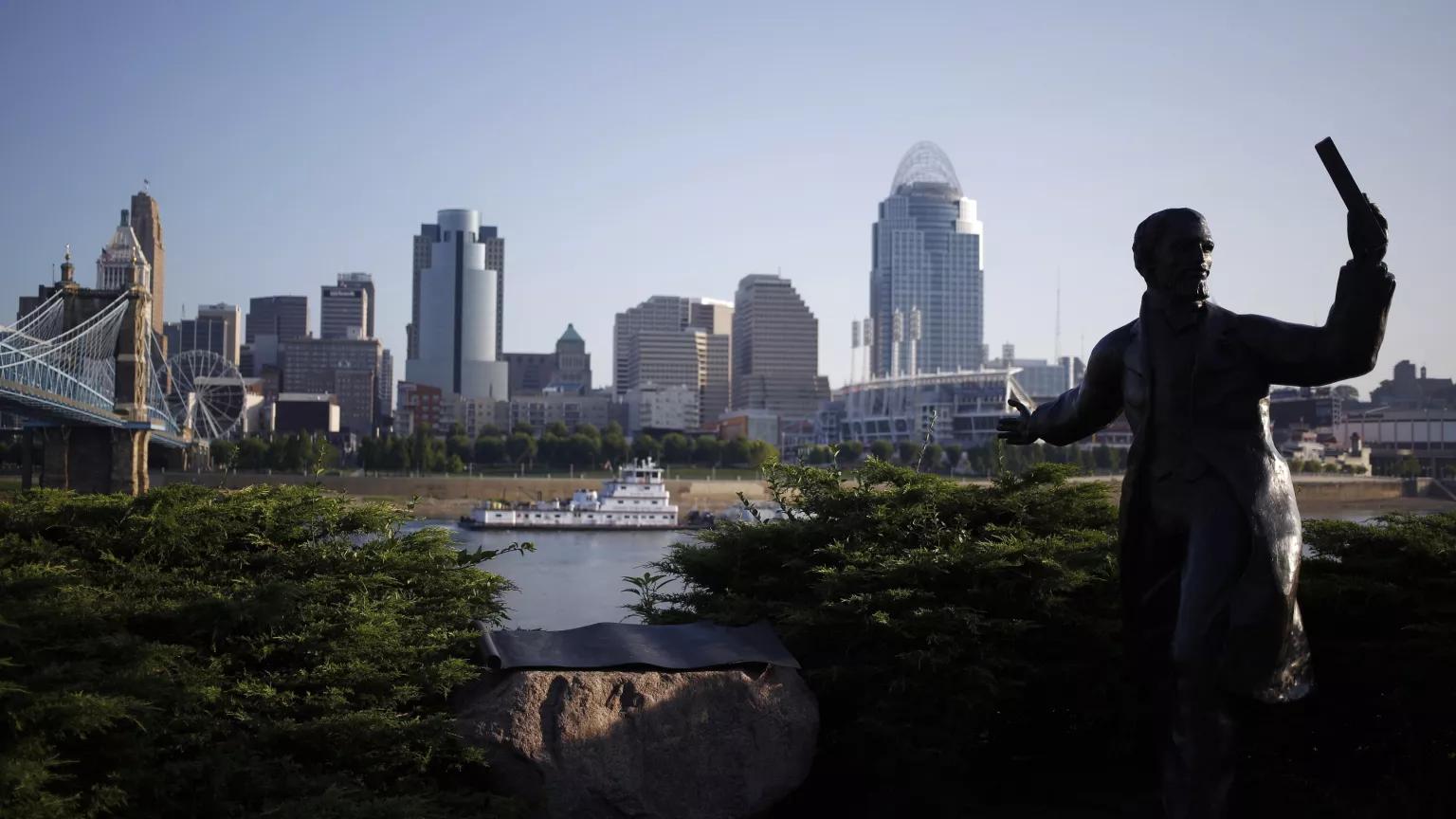

The Cincinnati skyline seen from the banks of the Ohio River

Photos by Luke Sharrett for NRDC

If asked, most Amercians likely wouldn’t guess that Cincinnati is one of the country’s top climate champions. At the intersection of Ohio, Kentucky, and Indiana, Cincinnati sits squarely in coal country. But the midsize metropolis has also been reducing its greenhouse gas emissions 2 percent each year since 2008, matching the decarbonizing rates of international climate leaders like Oslo and Paris.

“For generations, coal has been a primary source of energy and a primary economic driver here,” says Bill Scheyer, former city administrator for Erlanger, Kentucky, and current trustee of the nonprofit Green Umbrella, which works to maximize the environmental sustainability of Greater Cincinnati. “People in general were slow to let go of that, because it’s just been such a given part of their lives.”

But Green Umbrella has made incredible progress on that front since its founding in 1998. What began as a collection of volunteers who would meet in a local library to discuss ways to preserve green space has grown into a regional alliance that spans 10 counties in three states. Green Umbrella’s 200 member organizations and governments collaborate on everything from watershed preservation and reducing food waste to energy and transportation policies. Paired with ambitious climate planning at the city level, the group’s efforts have resulted in a cleaner, greener Cincinnati—from its grocery stores and banks to its police stations and zoo. And the Queen City is just getting started.

Cincinnati’s Lunken Municipal Airport, which is the site planned for the city’s 25-megawatt photovoltaic array

Small but Mighty

Minutes after President Donald Trump announced in 2017 that he would withdraw the United States from the Paris climate accord, Cincinnati Mayor John Cranley took to the steps of City Hall. There he told a crowd of reporters that Cincy would join the Compact of Mayors (now called the Global Covenant of Mayors for Climate & Energy), a coalition of now more than 10,000 cities and local governments aiming to collectively lower their carbon emissions by 1.3 billion tons per year by 2030. Days later, Cranley drove down Kellogg Avenue, “and I looked at Lunken Airport, and I looked at the Water Works,” and said to himself, “You know, why don’t we put up a bunch of solar panels—here, on this land we own?”

Within weeks, the mayor had committed the city to 100 percent renewable energy by 2035 and laid out a plan for a 25-megawatt photovoltaic array. With contracts currently under negotiation, the solar farm will power the Greater Cincinnati Water Works and the entire municipal government in what would be the country’s largest solar project owned and run by a city.

Last year the city also updated its Green Cincinnati Plan. Launched in 2008, the plan now includes 80 strategies for cutting carbon pollution to 80 percent below 2006 levels by 2050. And as one of 25 cities chosen for the American Cities Climate Challenge (ACCC)—a partnership between Bloomberg Philanthropies, NRDC, Delivery Associates, and several other organizations to reduce emissions in the buildings, energy, and transportation sectors—Cincinnati is furthering its commitments to renewable power generation and energy efficiency.

Carla Walker, the city’s climate advisor, who has been busy working to get more (and more affordable) electric vehicles on Cincy streets, says Cincinnati’s climate measures have made it a model for peer cities, such as Indianapolis and Columbus. With a population of 300,000, Cincinnati may be the second-smallest ACCC city, but when it comes to ambitious emissions cuts, it makes the top five. “We’re punching above our weight,” says Walker.

Districts of the Future

In fighting climate change, renewable power and energy efficiency work hand in hand. Cincinnati is among 22 American cities developing 2030 Districts, which are urban areas committed to slashing transportation emissions, energy use, and water consumption in half by 2030. So far, 25 Cincy property owners, developers, and commercial tenants have signed on, committing more than 20 million square feet—roughly the size of 25 Madison Square Gardens—to the 2030 goal.

One of Cincinnati’s crown jewels of efficiency is a police station on its west side. The District 3 Police Station, which reopened in 2015 on the site of a former car dealership, is the city’s first LEED Platinum building. Replete with a 329-kilowatt solar array, a geothermal heating system, and a rain garden, the $16 million building runs on its own energy—and it’s open 24 hours a day, every day of the year. This may be the most sustainable police station the country has ever seen. And in a city dealing with severe flooding issues and stormwater overflows, the native vegetation planted in the station’s new retention basin helps keep the site’s water in place. This makes Mary Jo Bazely, a volunteer who gardens and plants trees for the Cincinnati Parks Foundation, very proud. “There’s more green now. The water’s staying on site. It’s been remediated,” says Bazely before listing off several of the station’s energy conservation features that community members like herself made sure were included—right down to the outlets in the police lockers where officers can charge their cell phones and walkie-talkies with power from the sun shining outside.

But the net-zero police station is far from being the lone green jewel in this city. Tremaine Phillips, former director of Cincinnati 2030 District, can easily rattle off the achievements of several of the group’s partners.

Fifth Third Bank, headquartered in Cincy, is the first Fortune 500 company to purchase 100 percent of its electricity from renewable sources—in this case, a solar farm in North Carolina that “couldn’t have been built but for our contract,” says Scott Hassell, the bank’s director of environmental sustainability. The Kroger grocery chain, which is headquartered in Cincinnati and has nearly 2,800 stores across the United States, is committed to a Zero Hunger/Zero Waste program and has pledged to eliminate plastic bags by 2025. The Cincinnati Zoo, considered one of the nation’s most sustainable zoos, boasts the largest publicly accessible urban solar array in the country. And the headquarters of Procter & Gamble met its 2020 greenhouse emissions and water use reduction goals two years early (too bad the company remains bent on destroying the Canadian boreal, a forest critical to mitigating climate change) and has already achieved zero manufacturing waste at more than 80 percent of its sites nationwide. The list goes on.

On the Home Front

Since the 1970s, a sizable chunk—about 33 percent—of Cincinnati’s population has moved out, mostly to the suburbs. But Chris Heckman and his wife, Kristen Myers, recently planted themselves firmly in the city proper. “We wanted something different for our kids, something more sustainable,” says Chris, a designer and local environmental volunteer who spent years as a stay-at-home parent. The family of four, whose roots lie elsewhere in the Midwest, bought an 1870 home built in Over-the-Rhine (OTR), a rapidly gentrifying neighborhood just north of the business district. While some OTR streets host entrepreneurs sporting beards and Warby Parkers, other blocks are quiet canyons of vacant buildings.

The Heckman-Myers home had been one such vacant property. But with upgrades to its insulation, the addition of geothermal wells, rooftop solar panels, a Tesla Powerwall to store electricity, and a variety of other retrofits, the home is shooting for LEED Platinum certification. The family owns a car but usually takes public transit, including the Cincinnati streetcar, which runs in front of their house. (When Chris isn’t schlepping kids, he opts for a bike from the city’s bike-share program.) The Heckmans are eligible for federal tax refunds of 30 percent of what they paid for their solar and geothermal systems, and depending on the LEED level the house achieves, the household could be eligible for up to 15 years of city tax abatements, meaning they’d pay taxes only on the pre-improvement value of their property for those years.

“I’m proud that Cincinnati is a leader in pushing what’s possible with sustainability goals,” says Chris, “but we all live on the planet, and wherever we live, we’ll need to be improving our climate aspirations.”

Of course, not everyone can afford to get their home LEED certified. Half of Cincinnati’s children under the age of five live in poverty. In some neighborhoods, like Avondale, the median yearly household income is as low as $18,120. For this segment of the population, the share of their incomes devoted to energy bills is among the highest in the nation. The settlement of a recent lawsuit involving Duke Energy rates includes the utility paying $250,000 per year for the next six years to fund energy efficiency upgrades for low-income tenants.

Often overlooked in discussions of energy bills is the importance of trees. The shade they provide helps reduce the heat island effect, which lowers the need to crank up the A/C. This is especially important in lower-income neighborhoods, where many residents live without air-conditioning or have health issues that make them more heat-vulnerable. Cincinnati has 40 percent tree coverage, but this varies greatly among neighborhoods, with less-affluent ones having fewer trees. With a priority on tree-deficient areas, the city’s Street Tree Program spends roughly $2 million per year to plant trees along sidewalks, and its ReLeaf program so far has provided nearly 20,000 free trees for planting on private property throughout the city.

As the trees grow, so does Cincinnati’s resilience. Still, like many cities, Cincy has a long way to go before achieving its sustainability and equity goals. On this front, the Queen City is just getting started, but within the new Green Cincinnati Plan, each proposal includes details about how the sustainability measure will also increase equity. As before, Cincinnati is facing its climate challenges with eyes wide open—and will, one hopes, continue to impress.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

How You Can Stop Global Warming

A Consumer Guide to the Inflation Reduction Act

What Are the Solutions to Climate Change?