Lake Erie’s New Invasive Species May Be Tiny, But Its Ranks Run Deep

Here are billions of new reasons Congress shouldn’t go soft on ballast water.

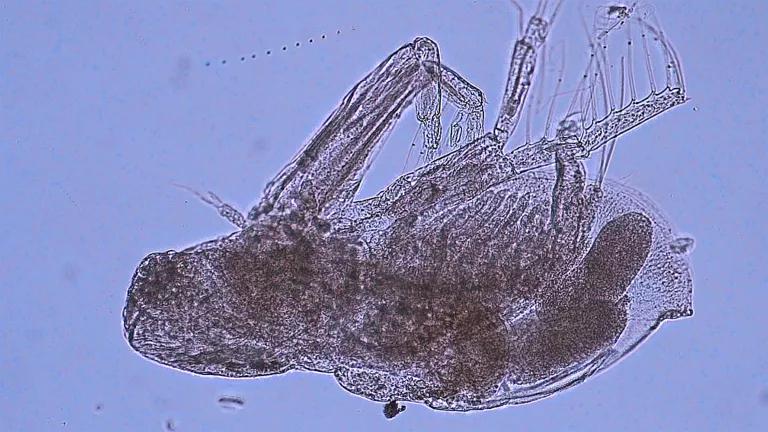

A microscope image of Diaphanosoma fluviatile

This summer scientists discovered that two more invasive species from faraway waters have settled into Lake Erie—already the reluctant home of the quagga mussel from Ukraine, the round goby from central Eurasia, and the Atlantic Ocean’s gnarly-mouthed sea lamprey.

The good news is that the newcomers are two types of zooplankton—microscopic organisms that form the base of aquatic food chains—and they aren’t likely to latch onto your calf the next time you take a dip in Lake Erie. The bad news is that scientists know hardly anything about these tiny animals and what destruction they may bring to the lake’s ecosystem and regional economy. The even worse news is that if Congress ever succeeds in easing ballast water restrictions—as the shipping industry has been trying to get it to do for years—more invasive species could soon be on their way to stay.

“Invasive species hurt the fishing industry, they hurt tourism, they hurt recreation, they devastate water quality,” says Rebecca Riley, legal director of NRDC’s Nature program. “The costs are high, and we’re all bearing that burden.”

The newly discovered Diaphanosoma fluviatile, a type of water flea, and Mesocyclops pehpeiensis, a copepod crustacean, likely got sucked into a ship’s hull, along with large amounts of water, somewhere in South America and Asia, respectively. This water acts as ballast to help keep a ship steady at sea when its hull would otherwise be empty. But as Riley explains, “The problem is, they pick the water up in one place and discharge it in another.”

This practice has transported some of the most notorious invasive stowaways to the Great Lakes, where they have wreaked havoc on native ecosystems. Parasitic sea lampreys, for instance, latch onto their hosts—lake sturgeon, brown trout, and other large fish—and suck their body fluids like leeches. Because Great Lakes fish have not coevolved with sea lampreys, they have few defenses against these lanky vampires and often die as a result. In fact, scientists estimate the lamprey explosion in the late 1940s reduced fish catches in the lakes from 15 million pounds preinvasion to just 300,000 pounds by the early 1960s.

This is why scientists aren’t exactly rolling out the welcome mat for Erie’s new water flea and crustacean. The finer points of their life cycles are unknown, but because zooplankton make up the base of aquatic food chains, these two tiny species could potentially pack a big punch.

When the spiny water flea (Bythotrephes longimanus), native to Europe and Asia, invaded Wisconsin’s Lake Mendota earlier this century, the entire lake went cloudy. The water fleas had gobbled up too many of Mendota’s other zooplankton, including species like Daphnia, which munches on algae. The spiny water flea helped prime the lake for toxic algal blooms, which have surfaced in each of the past two years. Not only are blooms like these potential fish killers, but they smell horrible and repel people who would normally fish, swim, and engage in other recreational lake activities. All in all, a 2016 study concluded it would take upwards of $140 million to get Lake Mendota to where it was before the spiny fleas showed up.

Erie knows a thing or two about algae, having in recent years suffered several of its own toxic blooms and subsequent drinking water disasters, though these blooms were caused by excessive agricultural runoff. Nevertheless, the mysterious new flea in town deserves our attention.

“There are many thousands of species of zooplankton globally and only a small fraction have been seriously studied,” says Reuben Keller, a freshwater ecologist at Loyola University Chicago. “When new species arrive, we usually have to wait to find what their impacts might be. By the time we discover those impacts, it is too late to do much to reduce them.”

Case in point: the zebra mussel. One minute there’s a new stripy bivalve catching our eye in the lake, and the next minute they are everywhere—literally. Between 1993 and 1999, this prolific bivalve cost the Great Lakes power industry an estimated $3.1 billion. The industry had to make the choice to either pay to remove the mussels from its structures and intake valves over and over and over again, or purchase pricey anti-mussel countermeasures such as sodium hypochlorite systems, which kill the mollusks outright, or anti-fouling paint that keeps them from latching onto certain surfaces. The former can cost around $60,000 per unit; the latter can run more than $80,000 per application (not counting labor, of course).

Keller says there are many ways a foreign species can find its way to the Great Lakes but very few safeguards in place to prevent it. This is why it’s so strange that, with so much money and so many livelihoods on the line, some congressional representatives have been looking to weaken the rules that we do have to keep invasives at bay.

The Clean Water Act currently requires the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to review ballast water safeguards every five years and determine whether to implement any new technologies—like ultraviolet lighting, chlorination, and other types of filtration systems—that could help. If so, and these improvements are deemed “economically achievable” (or not exorbitantly expensive), then the agency must make the standard stronger.

For years the shipping industry has been lobbying Congress to expunge ballast water from the Clean Water Act’s purview. One tactic legislators keep using, according to Riley, is trying to slip that gem of an edit into “must-pass legislation” such as the National Defense Authorization Act or the Coast Guard Bill.

In April, the last time the ballast regulations came up for a vote, the motion failed to pass by just four votes. So in addition to keeping a close watch on the doings of D. fluviatile and M. pehpeiensis, we’ll also need to keep an eye on Congress.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

Keeping an Eye on Tench, an Invasive Fish That’s Crept Into the Great Lakes

Can We Save the Midwest’s Only Rattlesnake?

How Fish Autopsies Help in the Fight Against the Invasive Asian Carp