When Art Captures the Wind and the Rain—and a Bit of Ourselves

“Weather Report” fills a Connecticut museum with the works of 25 artists who explore what’s happening in the atmosphere and, inextricably, to us.

Storm Prototype by Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle, 2007

Courtesy the artist and Rhona Hoffman Gallery, Chicago

The next time you turn on the Weather Channel or search an app for the weekend forecast, consider the role that you, the consumer, play in the weather report you seek. In the time it takes to read this paragraph, for example, the average person will breathe approximately four liters of air, a gaseous mix consisting of about 20 percent oxygen and 0.5 percent carbon dioxide. Yet when we exhale that same breath, according to Richard Klein, the exhibitions director of the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut, its gaseous composition changes to include 15 percent oxygen and 5 percent carbon dioxide. Our lungs and circulatory system take in what they need and expel what they don’t. Eventually, the air we breathe back into the atmosphere tens of thousands of times a day is absorbed by the leaves of plants and trees, which fall to the forest floor, yielding carbon-rich soil that nurtures our food.

In other words, we don’t just live in the earth’s ever-evolving atmosphere, otherwise known as the weather; it also lives in us. That’s one point of focus of “Weather Report,” a new exhibit that brings together works by 25 artists who share a preoccupation with the influence of wind, clouds, storms, drought, and other meteorological phenomena on the human experience. “Weather doesn’t only affect us physically,” says Klein. “Our immersion in the atmosphere and its various moods has a profound impact on our imaginations.”

Tondo by Nick Cave, 2018

Courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York

Inside the museum’s galleries in a small-town New England setting, “Weather Report” is a major atmospheric disturbance—of thoughts, materials, and artistic methods. Along with traditional representations of the esthetics of weather in painting and photography, the show presents sculptures, music, science-informed installations, and performance projects. The sampling of artists is also diverse, from internationally known Andy Goldsworthy and Nick Cave, whose large, fabric-covered Tondo overlaps Doppler radar images of a cyclone with brain scans of African-American youth suffering from PTSD because of gun violence, to Sara Bouchard, a university instructor and composer who arranges weather data collected in New York’s Central Park into lyrical musical sequences recorded on old-fashioned punch cards that are then played on a hand-cranked music box.

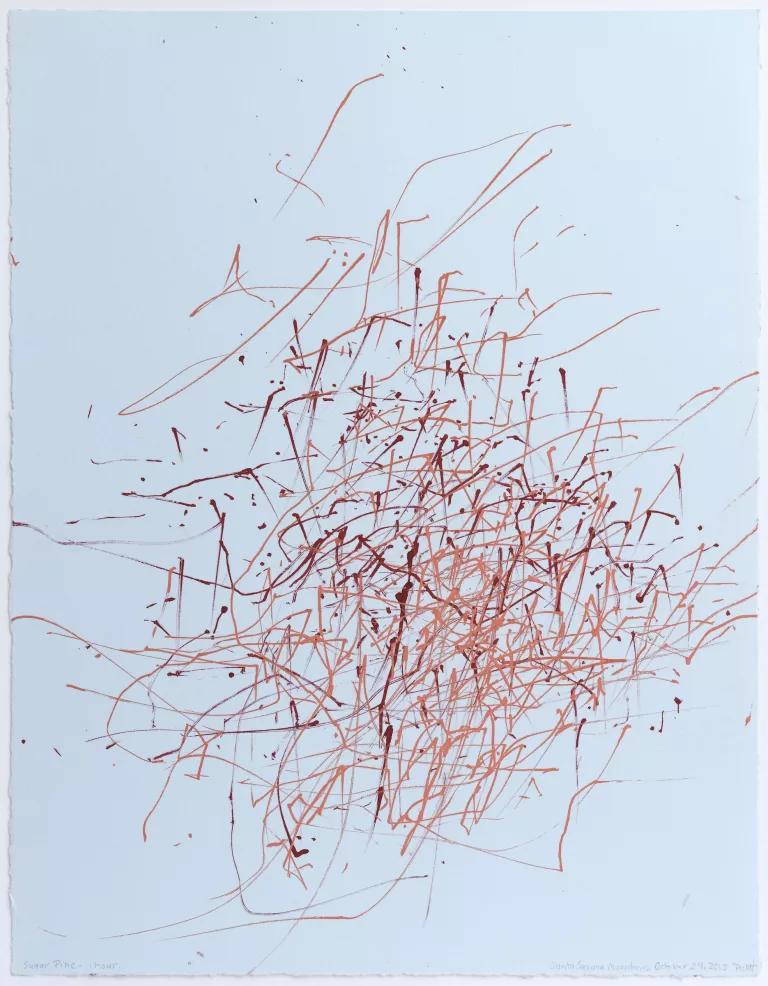

Ephemeral by nature, weather and the variable conditions that create it appear in formats both monumental and disturbingly intimate. California artist Pat Pickett, for example, experiments with delicate drawings that capture the wind’s movement through trees. She creates them by attaching colored markers to tree branches and positioning paper on a sturdy tripod next to them. The results—such as Sugar Pine—1 Hr. Santa Susana Mountains. October 29, 2015—have an almost journal-like quality, chronicling the raw reactions of a plant in a challenging environment.

Sugar Pine—1 Hr. Santa Susana Mountains, October 29, 2015, by Pat Pickett, 2015

Courtesy of the artist and the Drawing Room, East Hampton, New York

As the wind blows, the tree at the center of Sugar Pine sketches a complex mesh of short strokes. Pickett, whose practice combines the study of aerodynamics with an appreciation of the highly evolved mechanisms by which trees survive, says the drawings illustrate what a tree does “to save its life.” It chooses to bend rather than break. They also reveal the powerful force of wind, which is otherwise invisible.

Hanging nearby is one of the exhibition’s showstoppers, Storm Prototype by Iñigo Manglano-Ovalle. Suspended from the ceiling, a pair of huge metallic storm clouds, shiny but imposing, evoke the “terrible beauty” traditionally associated with representations of weather in Western art, but in the context of the global forces that shape society across political borders. Based on data from the Department of Atmospheric Sciences at the University of Illinois, the seemingly weightless forms are miniaturized scale models of an actual supercell thunderstorm that traveled over the Midwest in 2000.

Manglano-Ovalle has also made films of climatic events around the U.S.–Mexico border to highlight natural phenomena that occur over artificial but highly politicized boundaries. He became interested in weather systems like this one—which originated with El Niño in the Pacific Ocean thousands of miles to the south—as a metaphor for social, political, and economic climates as well as global migration, which is often connected to weather and climate conditions.

The Breath From Which the Clouds Are Formed by Ayume Ishii, 2015

Courtesy of the artist

Several other works in the exhibition take direct aim at the premise mentioned by Klein, that “by merely breathing, we participate in the atmosphere.” You see it expressed explicitly in Ayumi Ishii’s The Breath From Which the Clouds Are Formed, a series of 50 cloud and cloudlike images arranged in a grid. Half of the images are photographs of real cloud formations, while the rest are fluffy white impressions made by the warm breath of the artist on special heat-sensitive paper. She has literally contributed to the atmosphere, and she reminds us that, in the Anthropocene period, when human activity is the dominant destructive force on the planet, we all have.

“Weather Report” is on exhibit at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum in Ridgefield, Connecticut.

This article was originally published on onEarth, which is no longer in publication. onEarth was founded in 1979 as the Amicus Journal, an independent magazine of thought and opinion on the environment. All opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies or positions of NRDC. This article is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the article was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the article cannot be edited (beyond simple things such grammar); you can’t resell the article in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select articles individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our articles.

Looking for Climate Connections (and Berries) Through Traditional Indigenous Knowledge

How to Make an Effective Public Comment

From Dams to DAPL, the Army Corps’ Culture of Disdain for Indigenous Communities Must End