Overseas LNG Investment Undercuts U.S. Climate Credibility

A recent flurry of U.S. overseas LNG investments puts the Biden administration’s financing policies starkly at odds with the Paris Agreement’s warming goal.

Construction during an expansion of the Świnoujście LNG Terminal in Poland

With the United Nations climate change conference in Dubai (COP28) fast approaching, the global stocktake of progress toward the Paris Agreement’s goals will bring the Biden administration’s climate leadership credentials under greater scrutiny. While the United States has made foundational progress on the home front through the passage of landmark climate legislation in the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA), U.S. government policies and practices around overseas fossil fuel investment—and liquefied natural gas (LNG), in particular—undermine the country’s claims of global climate leadership and contradict the Biden administration’s commitments on overseas fossil fuel finance.

The recent flurry of U.S. investment in overseas LNG infrastructure is a glaring example of the Biden administration continuing to use taxpayer dollars to support infrastructure globally that is starkly at odds with the Paris Agreement’s warming cap of 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Immediate opportunities to change course

The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) negotiations on binding oil and gas export finance restrictions will serve as a litmus test for the Biden administration’s climate leadership intentions ahead of COP28. Supporting an OECD-wide fossil fuel finance exclusion policy would demonstrate much-needed follow-through on the administration's climate leadership aspirations, as well as its delivery on past commitments, including the COP26 Glasgow Climate Pact to end new direct public support for unabated fossil fuels in the energy sector.

And the administration can take an additional step before COP28 by publicly releasing updated guidance that restricts U.S. overseas financing of fossil fuels across all U.S. government financing agencies and across all types of financing. The Biden administration developed interim guidance that was never publicly released and included glaring loopholes in implementation.

Surge of U.S. LNG support overseas: DFC and EXIM

In recent years, LNG has solidified its place in U.S. international energy policy with $900 million of overseas public financing flowing toward procurement of U.S. LNG in 2023 alone. This concerted public sector investment is helping to draw private sector capital toward LNG projects across the globe by reducing the risk on projects that would be less attractive to private investors in the face of an impending transition away from fossil fuels. These investments also run the risk of locking the world into infrastructure that isn’t compatible with a 1.5-degree Celsius pathway.

U.S. development finance institutions and export credit agencies are helping to advance the expansion of LNG infrastructure, both through direct support of supply-side developments and demand generation for U.S. projects. In this way, the Biden administration is creating opportunities for further LNG expansion in instances where the private sector may not otherwise be inclined to do so. An examination of recent U.S. agency LNG transactions underscores these trends.

In 2023 to date, both the Export-Import Bank of the United States (EXIM) and the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) have provided financial support to secure demand for U.S. LNG exports. In June, DFC announced it would commit $500 million to guarantee Polish energy company Orlen’s loan obligations to Goldman Sachs for the purchase of U.S. LNG. This guarantee was announced six months after Orlen entered into a 20-year contract with U.S. LNG provider Sempra for the purchase of LNG from Sempra’s planned Port Arthur, Texas, liquefaction facility. Sempra’s contract with Orlen helped the Port Arthur Phase 1 project move forward and ultimately reach financial close in March of this year. The Port Arthur project will have a life span well past 2030, when the International Energy Agency (IEA) projects that fossil gas demand will need to decline by more than 63 percent below today’s levels by 2040 to be compatible with a 1.5-degree Celsius pathway.

EXIM similarly approved a transaction to support LNG procurement in June of this year, backing a $400 million line of credit for energy trader Trafigura to purchase U.S. LNG volumes, primarily to resell into European markets.

EXIM also has a recent history of direct support for LNG supply projects more broadly, investing in the Freeport LNG and Mozambique LNG liquefaction terminals in 2021 and 2019, respectively. Moreover, EXIM’s list of projects currently pending approval includes the Papua LNG Project, a proposed export terminal in Papua New Guinea that is facing significant civil society opposition. In addition to the deep climate concerns around furthering the expansion of LNG infrastructure globally, there are financial concerns about the potential return on investment, given the limited progress of project developers in securing contracts with prospective buyers for the LNG volumes produced by the Papua LNG facility. The Papua and Mozambique LNG projects expose the United States and American taxpayers to significant downside risk, given the projected structural reduction in global gas demand over the lifetime of these projects.

Climate credibility of U.S. LNG expansion

These transactions are often framed as support for European allies’ diversification away from Russian gas supplies, as being better for the climate than the alternative, and as being more aligned with a 1.5-degree Celsius pathway. However, these arguments fail to stand when the details of the project are held up to the sunlight. Remember, these projects typically only come online late in this decade, and all have a legacy lasting beyond 2030.

European gas demand is declining. In the face of the illegal Russian invasion of Ukraine, Europe had to rapidly change course on its supply of gas, given how dependent it was on Russian exports. Europe has both diversified its supply and dramatically shrunk its overall gas demand in response. According to the IEA, steps to reduce demand for fossil gas in Europe made up the majority of the European Union’s efforts to address its “missing gas supply” (see IEA Box 2.1). And this trend of shrinking gas demand in Europe will likely continue as the E.U. recently increased its renewable energy target and continues to take steps forward in energy efficiency (e.g., its rapid heat pump expansion). Any U.S. LNG project—such as the Trafigura or Sempra project—coming online later this decade will enter a European market of shrinking fossil gas demand.

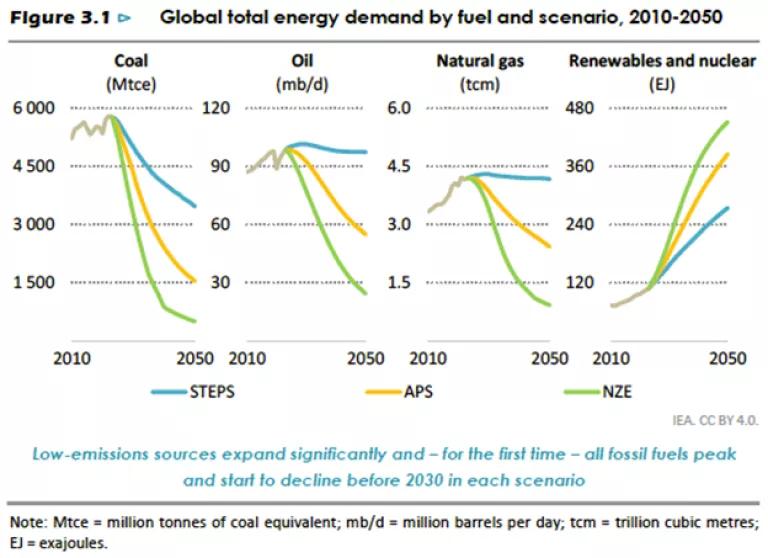

Global fossil gas demand will need to decline to meet our climate goals. The significant greenhouse gas emissions from these and other fossil fuel projects run counter to the Biden administration’s goal of climate leadership and efforts to meet our 1.5-degree Celsius goal. Any LNG project with a life span beyond 2030—e.g., the new Port Arthur facility, the Calcasieu Pass 2 LNG export facility in Louisiana, or the TotalEnergies purchase deal that extends to 2050—runs smacks against the trend that leading energy analysis says is necessary to meet our climate goals. As the IEA recently stated in its 2023 World Energy Outlook: “Since natural gas demand peaks in all WEO scenarios by 2030, there is little headroom remaining for either pipeline or LNG trade to grow beyond then.” And an even sharper decline in fossil gas is needed to meet a 1.5-degree Celsius trajectory, with the IEA projecting that fossil gas use will need to decline by 19 percent from 2022–2030 and by 47 percent more from 2035–2040 (see figure – NZE is its 1.5-degree Celsius pathway).

World Energy Outlook 2023, IEA

LNG’s poor life-cycle greenhouse gas emissions analysis

These LNG projects are also touted as “good for climate” since proponents argue that they are displacing hypothetical coal expansion, despite evidence that U.S. LNG export are competing with renewables, not coal. But new commentary from a credible expert on life-cycle emissions asserts that under all scenarios, increased LNG is significantly worse than coal. On short trips (e.g., from the United States to Europe), it is 24 percent worse than coal, and on long trips (e.g., to Asia), it is 200 percent worse.

Inklings of clean energy export promise

Recent deals, like EXIM’s $900 million solar power investment in Angola and similar solar financing in Honduras, demonstrate that opportunities to invest in clean energy exports at scale can be cultivated. DFC has also been able to invest in significant projects, including two $500 million solar manufacturing projects in India (here and here) and several recent electric vehicle projects.

With sufficient development work from expert staff within these organizations and a clearer change of direction within these agencies, we are confident that EXIM can do more than one large renewable project every two years and that DFC can continue to significantly ramp up its clean energy investments.

To demonstrate credible global climate leadership in its overseas energy investments, the Biden administration should:

- Fully implement and close loopholes in its “Interim International Energy Engagement Guidance” to restrict overseas fossil fuel finance across all federal agencies, including at DFC, EXIM, multilateral development banks, and through all U.S. government tools;

- Support dramatically scaled up renewable energy finance overseas instead of continued investment in expanding LNG and other fossil fuel infrastructure;

- Support an OECD-wide overseas fossil fuel finance exclusion policy to drive climate action at the global stage.