Equitable Building Decarbonization Across the Country: 2022

Policies and programs aimed at new construction and existing buildings continue to gain traction as communities and elected officials realize the feasibility and benefits of ambitious and equity-centered action.

Part of NRDC’s year-end series reviewing 2022 climate and clean energy developments

When most people think of the greatest climate offenders and the greatest climate opportunities, few have buildings at top of mind. But considering that the vast majority of our living and working takes place inside of buildings, it should come as no surprise that they are a crucial piece of the climate puzzle. In the United States, buildings account for nearly 40 percent of greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions. Fortunately, we saw growing momentum on equitable decarbonization in the buildings sector over the last year, at the local, state, and federal levels.

A significant number of local and state laws, standards, and building code updates were passed to require new buildings to be constructed all-electric or all-electric ready, even in places that were previously hesitant to act. This progress marks a significant step toward getting new buildings off of fossil fuels and powered instead by clean electricity as more of the grid transitions to renewables. We’ve also seen a steady pace of increased efficiency and electrification of existing buildings, with building (or building energy) performance standards (BPS or BEPS), increasingly gaining traction. Appliance standards—requiring the sale or installation of clean electric equipment for cooking, clothes drying, and water heating—have seen adoption as well. Cities and counties continue to lead, pushing for many of the most ambitious policy gains, often spurring action at the state level as feasibility and benefits of action become harder to ignore. The federal government also stepped up with historic legislation and funding to support efforts nationwide. And as more communities get involved in the push for building decarbonization, there is a growing awareness of the power of these initiatives to improve people’s lives by increasing affordability and decreasing energy burden while working in concert with efforts around energy and housing justice.

Three years into a global pandemic, the importance of having healthy, safe homes, schools, and workplaces has never felt more essential to our collective well-being. We rely on these spaces to provide personal haven and resilience. At the same time, the impacts of an increasingly volatile climate—devastating wildfires, more frequent and stronger hurricanes and tropical storms, ever-more-common 100-year flooding events, and summers with growing numbers of dangerous heat index days—are hitting closer and closer to home every year, displacing people from their homes and communities, or rendering the systems they have for keeping those homes safe and comfortable insufficient or too expensive to manage.

We are in the midst of a series of intersecting crises that all touch on buildings and the costs associated with living in them: high inflation, rising energy costs, climate devastation, and a continuing pandemic—fueling a new appreciation for buildings as a frontline in the fight not just for climate justice but for social and economic justice. Applied correctly, the tools we have for fighting climate change in our buildings can be leveraged to make people’s lives better.

New construction

Montgomery County, Maryland, passed legislation requiring new residential and commercial buildings to be all-electric (with some exceptions) and to be equipped with electric hot water systems and heat pumps for space heating and cooling instead of gas-fired appliances, including stoves. The new building standards kick in no later than December 31, 2026, with the option for the county executive to move more quickly for most building types. The county is one of the first in the mid-Atlantic to ban gas in most new buildings; Washington, D.C., previously banned gas in most new construction, starting in 2026.

The Chicago City Council passed the Energy Transformation Code, which exceeds the 2021 International Energy Conservation Code (IECC) and advances the city’s decarbonization commitments. One of its major requirements is for most new buildings to be built with the electrical capacity and wiring necessary to accommodate all-electric appliances for cooking, clothes drying, and water heating. At the state level, Illinois continues to work on a stretch code that, when finalized, will be more stringent than the Illinois base energy code and will allow municipalities who wish to adopt it to advance more quickly toward their energy efficiency and carbon emissions reduction goals.

In Kalamazoo, Michigan, Consumers Energy is conducting a pilot program providing Affordable All-Electric New Homes. The pilot showcases how high-quality, sustainable housing can be built to be made accessible to low- and moderate-income consumers. The homes are highly efficient, have all-electric heating, cooling, and cooking appliances, and are solar panel– and electric vehicle–ready. Bill information will be collected from residents in these homes to demonstrate utility bill savings versus less efficient or fossil-fueled homes.

Los Angeles passed a new buildings electrification code, mandating all-electric new building construction as the first major policy operative to result from its process, which is grounded in energy justice. A full summary of progress on buildings in Los Angeles can be found in our 2022 Sees LA Make Strides on Climate Justice blog post.

At the state level, the California Public Utilities Commission ended line extension allowances for new gas connections, removing a subsidy for gas system expansion. Additionally, the California Air Resources Board’s State Strategy for the State Implementation Plan, adopted in September 2022, established a zero-emission standard for new residential space and water-heating appliances starting in 2030. A full summary of progress on buildings in California can be found in our CA Clean Buildings Progress Report: 2022 blog post.

The Washington State Building Code Council (SBCC) adopted the strongest, most climate-friendly statewide building energy code for new construction. When the code goes into effect in July of next year, all new commercial and large multifamily buildings will be built with high-efficiency electric systems (heat pumps) for space and water heating and tighter envelopes, so less of that heat is wasted through leaks to the outside. The new residential building code requires that all space heating be provided by ultra-efficient electric heat pump systems that can run on 100 percent clean power (with limited exceptions for electric resistance and fossil fuel backup in very cold climates). It also requires that all single- and two-family homes and townhomes be outfitted with similarly efficient, clean heat pump water-heating systems, and increases ventilation requirements for gas stoves, improving indoor air quality and protecting residents’ health.

Colorado passed House Bill 1362, requiring cities and towns that update any part of their building code to adopt the 2021 IECC. Additionally, the law requires participating municipalities to include electric-ready provisions in their new codes to ensure that homes that are not all-electric today do not have to incur unnecessary costs in the future. It also requires participating municipalities to adopt a “zero carbon” code in 2030.

In New York, the Advanced Building Codes, Appliance and Equipment Efficiency Standards Act of 2022 was signed into law by Governor Kathy Hochul on July 5, 2022. The standards established by the new law will save 164,000 MWh (megawatt hours) of electricity—more than New York State used in 2020—and will save New York consumers $15 billion in the next 15 years, with $6 billion of those savings for low-income consumers. The bill also enables future building codes to align with the Climate Leadership and Community Protection Act (CLCPA), New York State’s landmark climate law passed in 2019, which shapes the state’s energy, environmental, and transportation policies for the next generation, which will enable the incorporation of greenhouse gas savings and lifetime savings from efficiency measures, creating healthier and more comfortable, climate-friendly homes into the future.

At the federal level, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) announced a proposed rulemaking to electrify new federal buildings and federal buildings undergoing major renovations. Beginning in 2025, these buildings will be required to reduce their on-site energy-related emissions by 90 percent, compared to 2003 levels. In 2030, full decarbonization of on-site emissions for new federal buildings and major renovations will be required. These measures will help achieve President Biden’s goal of net-zero emissions in all federal buildings by 2045. Learn more about federal progress on building codes in our 2022: A Banner Year for Building Decarbonization blog post.

Existing buildings

Montgomery County, Maryland, passed its Building Energy Performance Standard (BEPS), which will establish energy use reduction requirements for buildings larger than 25,000 square feet that ratchet down tp interim targets starting in 2028, reaching final targets starting in 2033. With support from the City Energy Project, a national initiative from NRDC and the Institute for Market Transformation (IMT), Montgomery Co. became the first county in the United States to pass a BPS policy, which builds on the county’s previously established Building Energy Benchmarking policy.

The same month, the state of Maryland passed the Climate Solutions Now Act, establishing a complementary BEPS (together with Montgomery County, these are the ninth and tenth such policies in the country) for buildings above 35,000 square feet, achieving a 20 percent reduction in direct emissions by 2030 and net-zero emissions by 2040. It also set a statewide GHG reduction goal of 60 percent by 2031 and net-zero by 2045, and required energy-efficient upgrades for hundreds of thousands of low-income residents, on whom an unfairly large share of the energy-cost burden falls.

Honolulu, supported by the American Cities Climate Challenge, passed the Better Buildings Benchmarking Program requiring annual benchmarking and transparency of energy and water use for commercial and multifamily buildings larger than 25,000 square feet and public buildings above 10,000 square feet, starting with the largest buildings in 2023. Roughly one-third of O`ahu’s total greenhouse gas emissions come from the building sector, and the city’s Climate Action Plan identified benchmarking as an important step in reaching its goal of net-negative emissions by 2045. The benchmarking program is expected to reduce the electricity consumption of large buildings by nearly 7 percent by 2030 and help curb greenhouse emissions on the island.

Boston launched a Green New Deal for its public school buildings, a $2 billion plan to retrofit and revitalize school facilities and to reimagine them as community hubs for climate resilience. The city envisions the plan as a way to accelerate decarbonization of its building sector while delivering urgent improvements to environmental health, justice, and safety for students, families, and educators. The 14 new school construction and major renovation projects will support citywide climate action while also building community resilience to extreme weather events.

In Michigan, two of the largest electric utilities, DTE and UPPCO, rolled out heat pump pilot programs. These pilots covered upgrading electric resistance heat in existing households and switching out propane furnaces with efficient, electric air source heat pumps in Michigan’s Upper Peninsula.

In Illinois, as part of the implementation of the Climate Equitable Jobs Act (CEJA), advocates including NRDC successfully helped to renegotiate the 2022-2025 energy efficiency portfolio plans for investor-owned electric utilities ComEd and Ameren Illinois to comply with the energy efficiency provisions in the new law. The new plans included significant, expanded investments in low-income energy efficiency programs for single-family and multi-family households ($113 million for ComEd and $36.9 million for Ameren) including first-ever offerings for efficient electrification retrofits for both utilities ($10 million for ComEd and $2.2 million for Ameren).

California committed $1.4 billion in funding for clean buildings. This includes $922 million to ensure the state moves its Equitable Building Decarbonization (EBD) goals forward, providing efficient electric appliances and other improvements to low-income families with a program model that engages community-based organizations and ensures protections for renters. There is also $270 million for Community Resilience Centers, which will upgrade or build vital gathering places (community centers, libraries, schools, etc.) with efficient electric technology, energy efficiency, renewables, and battery storage. The already successful TECH Clean California program to develop the market for heat pump technology across the state received an additional $145 million as well. Learn more in our CA Clean Buildings Progress Report: 2022 blog post.

New York passed the Utility Thermal Energy Network and Jobs Act, requiring investor-owned utilities in the state to propose pilot thermal energy network projects, connecting buildings via underground pipes to a joint thermal loop that’s fed by shared geothermal well fields and other heat sources. Used strategically, these systems can help provide large-scale decarbonization for communities.

At the federal level, the National Building Performance Standards Coalition, launched by President Biden and the Council on Environmental Quality in January of 2022, catalyzed a group of more than 30 local and state governments to commit to developing building performance standards by Earth Day, 2024. As of December 2022, the governments of the National BPS Coalition represent about a quarter of the buildings in the United States. Also in December of 2022, the Biden administration announced the first-ever Federal Building Performance Standard, setting an ambitious goal to cut energy use and electrify equipment and appliances in 30 percent of the building space owned by the federal government by 2030.

A growing focus on equity

For many, 2022—and its myriad social, economic, and environmental crises—brought the realization that buildings are where climate change and everyday life intersect, and that finding pathways to meeting energy needs without fossil fuels can and must be a tool for improving people’s lives.

A rapidly growing number of state and local governments across the country are acknowledging this and, more importantly, taking meaningful steps to develop, enact, and implement policies and programs that not only address climate but do so while centering equity and community needs.

Los Angeles launched its first Climate Equity LA engagement series, co-designed by city officials and community leaders to discuss equitable building decarbonization strategies. Discussions are oriented around energy and housing justice principles supported by a broad base of advocates, centering equity and community recommendations in the policy process.

In exploring a potential BPS, Portland, Oregon, followed a co-created, community-led engagement model to elevate the voices and decision-making power of BIPOC communities and close the racial justice gap. As a result, the city is pursuing “climate and health standards” to show that its building performance policy approach addresses more than just carbon emissions.

In Orlando, Florida, Poder Latinx worked with IMT to explore how a BPS policy could be leveraged to address the priorities of the Latinx community, summarized in a report of recommendations.

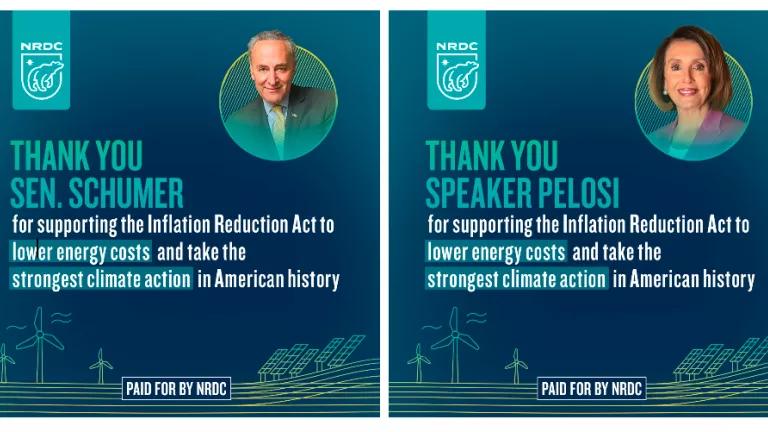

With the Inflation Reduction Act, the United States has passed the most significant climate legislation in its history, but reaching its full economic development and emissions reduction potential will require state and local governments to act quickly and ambitiously on implementation. And with the establishment of the Justice40 Initiative, there is an unprecedented opportunity to channel those potential benefits into the communities that are most vulnerable to climate change, and who have suffered the most from disinvestment and racial discrimination. However, whether or not those benefits materialize will depend on thoughtful and inclusive implementation at all levels of government. By building on the progress made in 2022 across cities and states and maximizing the potential of these landmark federal programs, we can make even more progress in 2023 and beyond to decarbonize buildings in a way that continues to address affordability and provide access to holistic, healthy, and affordable homes, schools, and workplaces.