Can the Shift to Clean Energy Be Both Fast and Fair?

A look at the promise and principles of a just transition and the impact of the recent debt ceiling deal and FAST-41.

The South32 Hermosa Project site in Santa Cruz County, Arizona.

Chris Mooney/South32

In our first post of this series—examining the nation’s energy transition and the need to center considerations of justice—we highlighted the work of the Climate Justice Alliance and its Just Transition Framework. The framework sets out a series of threshold questions to ensure projects in the clean energy transition also live up to the calls for a just energy transition.

Proposed projects should:

- Define and identify marginalized groups implicated by a project

- Do a holistic review of the region’s social, ancestral, and environmental history

- Assess the communication and involvement of representative community groups

- Candidly review existing inequities (e.g., economic, social) using regional data

- Build systems of accountability for equity work moving forward

NEPA—the National Environmental Policy Act—is intended to do just this. NEPA was signed into law on January 1st, 1970, to require federal agencies to determine the environmental impacts of their proposed actions before finalizing decisions. NEPA can cover a range of federal decisions from permit applications to federal land management actions. Moreover, its process leads agencies to review the environmental, economic, and social effects of a proposed action with the opportunity for a public comment period and review of its assessments. In an ideal world, NEPA would yield such quality community engagement that it would lead to the improvement of projects before they are built, thus minimizing impacts on nearby communities.

But when Congress raised the debt ceiling with the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023, it rewrote NEPA in critical ways. It is now an open question whether federal decisionmakers retain the necessary tools under NEPA that both advance the principles of a just energy transition, and ensure community buy-in and participation in decisions concerning publicly entrusted resources, federal permits, and other significant federal actions.

Here’s how Congress recently changed NEPA:

- Environmental reviews must abide by arbitrary, shortened review timelines

- Environmental reviews must now be kept within arbitrary page limits

- Project proponents have a right to petition to prepare environmental impact assessments and statements for their own projects

- Project proponents can apply to the courts to force agencies to complete environmental reviews by a set date

- A lead reviewing agency must be designated, regardless of the complexity of a project’s permitting needs

This matters for communities and those on the frontlines of potential energy transition impacts because NEPA’s environmental review process is often their only viable avenue to raise concerns about projects likely to affect their lives. It’s often solely NEPA's requirements that ensure communities are given legal notice of any proposed activities.

In general, faster timelines may limit opportunities for engagement and arbitrary page limits on environmental documents are certain to reduce transparency, the quality of the data provided, and, most vitally, the sharing of information critical for communities to adequately assess a proposal’s full scope of impacts.

Proposed Arizona Mine Offers a Look at Expedited Review in Action

The transportation sector has already begun exploring how to speed up environmental review without sacrificing fairness to communities or their opportunities for input. In 2015, the Fixing America’s Surface Transportation Act (FAST-41) created a new federal agency called the Permitting Council. Subsequent legislation and actions by the Permitting Council have broadened FAST-41 to cover eighteen economic sectors, including mining. Before the debt ceiling law took aim at NEPA, the Council had accepted the first hardrock mine for consideration under FAST-41's expedited review provisions. It’s a project proposed by South32 looking to extract and process zinc and manganese south of Tucson, Arizona known as the Hermosa Mine.

If all goes well, this could be an important case study in how America can move quickly to meet upstream supply chain demands for raw materials needed for things like high-capacity batteries and other clean energy technologies.

In the mining and critical minerals context, the challenges of striking a balance between moving expeditiously and taking concerns around justice and community impacts seriously are made more difficult by the General Mining Act of 1872. This infamous artifact from the 1800s is truly a piece of its time, ridden with a colonialist basis that enforces a disregard for Indigenous sovereignty and consent. In this earlier piece, we explain the origins of this Gold Rush-born law that continues to govern land use for mining across nearly a quarter of the United States.

On a very loose leash, extractive companies are free to inspect federally managed lands for significant mineral resources that would grant them the pass from agencies to extract hardrock minerals. The legislation allows mining to then override other uses local communities may need and want, including recreation, hunting, or the conservation of essential fresh water supplies. Although almost every Western state and Alaska charges a royalty or severance tax covering federally owned minerals, these minimal payments to states do little to remedy or alleviate the negative impacts of projects. Damage to underserved communities and intricate ecosystems will still happen even if the state receives some monetary compensation. And even though these states charge royalties or severance taxes, no royalties are paid to the federal government, which is often left on the hook to pay for eventual clean-up in the absence of other financial measures like adequate bonding. All this means taxpayers are often left with costly and actively polluting abandoned sites and few of the economic benefits from the profits mining companies accumulate during a mine’s operational life.

151 years of mining under this legal regime has had the following effects on the environment and human health:

- As of 2017, the BLM and EPA recorded at least 140,000 abandoned hardrock mine features, like tunnels and toxic waste piles, in the U.S.

- 67,000 of these abandoned mine features have been noted to pose safety hazards, and 22,500 may be causing environmental harm

- The 2015 Gold King Mine disaster in Colorado released about 3 million gallons of contaminated water and heavy metals into Cement Creek. Diné (Navajo) people close to the mine continue to deal with its effects on drinking water and farming

- The EPA estimated that mining is the culprit for the pollution of 40% of watershed headwaters in the Western region

- According to the 2021 Toxics Release Inventory, the metals mining industry is the single largest source of toxic pollution in the U.S., comprising 44% of all reported toxic releases that year

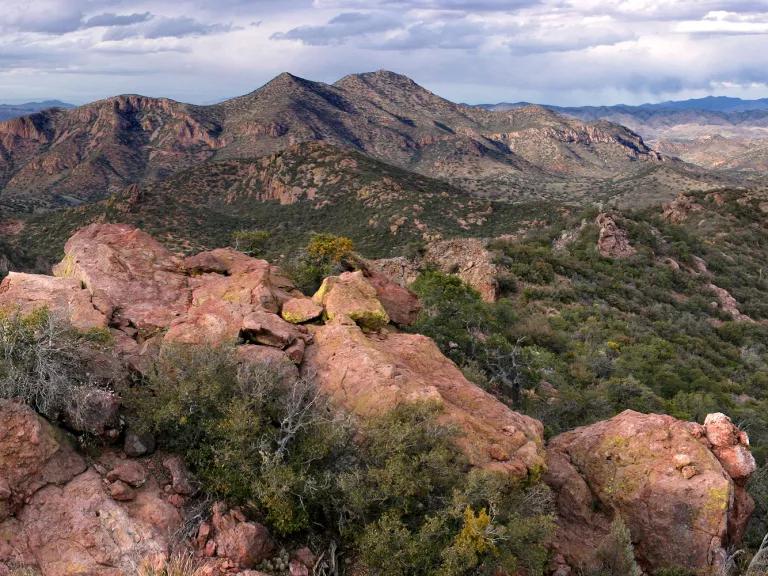

A view over the Patagonia Mountains in Southern Arizona.

Patrick Alexander

This brings us back to South32’s Hermosa Mine project. Community members have been vocal in opposition due to the feared impacts the mine could have on the local hydrology and the specter of long-term pollution. Simultaneously, the project is poised to be a significant source of manganese and zinc, both designated critical minerals for domestic renewable energy technology production. The project would spread across 30 mining claims with an area of 228 hectares (or nearly one square mile). The actual mining at the site will use what’s known as long-hole open-stoping to reach the mineral deposits deep underground. This process involves creating multiple tunnels at different angles to access the ore body.

A project of this scale will inevitably cause pollution of surrounding ecosystems, and nearby residents have expressed their discomfort at the impending loss of the pristine character of the landscape as this project begins to take shape. Some residents also worry about potential accidents and spills and their effects on the local environment. The Patagonia Area Resource Alliance (PARA) has called attention to the Patagonia Mountains and its wildlife corridor providing a home to jaguars and ocelots.

As of this writing, the good news is that the US Forest Service has also approved the local municipality, Patagonia, Arizona, to act as a “participating agency” following their request to be closely involved in the permitting process. This approval is promising, and a step in the right direction to ensure close engagement and communication with the local community. The discussions community members held amongst themselves have led to a favored project alternative for the proposed mine that could mitigate several of its adverse impacts on biodiversity and hydrological flow.

If acting agencies and South32 proactively respond to the community’s concerns, we hope to see action on their request for funding a hydrologist to study the potential hydrological impacts of their preferred alternative. Since the permitting process is still in its early stages, just and equitable actions—consisting of transparency, sharing information, gathering community input, and adjusting project design to address concerns—at the start will help shape the outcome of the Hermosa project in Santa Cruz County. Although meeting the community requests mentioned here will not produce approval from residents across the board, it can lead to better outcomes residents seek and may reduce the level of controversy the project would otherwise face.

With procedural improvements, the FAST-41 legislation could cut legitimate organizational time wasters without reducing critical time spent reviewing the positives and negatives of a project. The implementation of FAST-41 and its application to qualifying projects has been improving for project categories outside of mining in the last couple of years. In 2022, there was just one missed deadline reported by the Permitting Council. This efficiency demonstrates that cuts to timelines and the depth of detail contained in environmental review documents are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

At the same time, efficiency alone cannot be the goal of permitting processes. Deep and careful communication with the communities near proposed projects and collection of their opinions and concerns can help reduce delays caused by community opposition. To this end, the Permitting Dashboard holds the potential for being a strong tool to enhance transparency. However, measuring and confirming accessibility and awareness of the Dashboard and the information it contains must be part of the Permitting Council’s core work if the FAST-41 model is to be more widely and successfully adopted.

The town of Patagonia, Arizona.

billandkent via Flickr, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. https://www.flickr.com/photos/billandkent/419340789

To achieve these more positive outcomes in review and permitting process, the following areas should be kept in mind for the implementation of the FAST-41 legislation—and the revised provisions of NEPA—moving forward:

- Proper communication with Indigenous and other marginalized communities goes beyond an introductory meeting; information on the proposed project should be made accessible in both language and medium

- Research shows major reasons for delay in reviews and/or permitting often includes low agency funding, limited staff capacity, and staff turnover (i.e., “brain drain”)

- Organizational tools like a list of all needed information from applicants at the start of project review can prevent unnecessary delay

- A thorough, unrushed permitting process should be framed as positive since its results may help reduce controversy and prevent opposition from marginalized groups and impacted communities, assuming that thoroughness was, in part, due to greater effort spent engaging with those groups and communities

If the right balance between clarity in the permitting process and a thorough review of the environmental and social impacts is achieved by the range of stakeholders involved, some level of increased, responsible domestic critical mineral production may be within reach. But to do so requires taking lessons learned from the past century of resource extraction to heart. To decrease the probability for environmental and social harm to communities that we’ve seen in fossil fuel projects, for example, the just transition frameworks of equitable inclusion and support for marginalized communities must be kept front and center for projects meant to support the clean energy transition. The efficiency seen in FAST-41-managed projects may provide lessons in organizational efficiency that could allow not only appropriate levels of engagement with communities but also cut down on interagency bottlenecks that, in some cases, can unnecessarily slow environmental and permitting reviews.

Passage of the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023 will provide a second test case and one that will require agencies to act even more purposefully if they wish to gain community input and buy-in for projects under review. With the changes to NEPA contained in that bill, the imposition of arbitrary timelines and page limits creates a substantial risk that frontline communities will have fewer opportunities to engage in the review and permitting process. The handouts to project developers that give them greater control over environmental review writing and completion could also kneecap meaningful community engagement and inappropriately tip the scales in favor of project developers, regardless of community support. It will be up to agencies grappling with these changes to remember that the principles of Just Transition not only further equity and justice goals but have also been found to help overcome many of the most difficult obstacles in the permitting process because local community buy-in reduces controversy and may even lead to a level of acceptance for projects that might otherwise be lacking.