The Miller Center at the University of Virginia (full disclosure: my alma mater) rolled out its latest report, fittingly entitled “Are We There Yet? Selling America on Transportation” (pdf here). It’s based on a conversation they convened last fall, which in turn was a session following up on a 2010 conference on transportation policy. They invited 60 of us transportation wonks – including, for the first time, five former Transportation Secretaries -- to discuss the main challenge facing the federal program now: How to reconcile the demonstrated need for investment and policy reform, and the plethora of good proposals for doing so, with the staggering dearth of public demand and therefore political will to enact such ideas?

The report is slim and well-worth a close read since while some of it re-treads what’s known, there are several new insights inside, and the authors propose a laudable transportation campaign strategy.

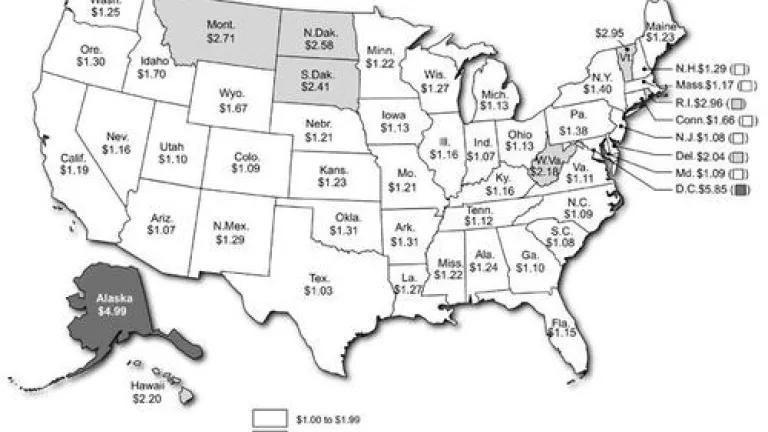

Regarding insights, for example, there’s a map on p. 17 that’s reproduced from a GAO report from last year:

This is a remarkable map, explaining several things. First, it shows why there has been no “donor-donee” fight this reauthorization cycle. The 1998 transportation bill was called the Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century, or TEA-21, and the “equity” stood not for income inequality but for this donor-donee question. This has been a perennial food fight in transportation – donor states, who contribute more than they get back from the transportation program via the federal gas tax, have always carped about this fact and argued that their rate-of-return should be higher. I kid you not, there were brawls over single-digit percentage differences in the guaranteed rate-of-return for states. As the Congressional Research Service has reported, these fights were routine going back at least to 1982 (pdf of their historical analysis here).

Lack of money has erased that debate entirely; every state is now in the “donee” column, taking this off the table. This is not all bad, since it was kind of a silly debate and along with parochial earmarks distracted Congress from bigger policy questions. And a second implication of this is that shoring up state transportation programs is now contributing to the federal deficit. The report reminds the reader that just since 2008 $61.2 billion worth of deficit spending has propped up the transportation program.

The report also usefully distills the sobering clash that has overcome renewal of transportation law:

Two imperatives have collided: on the one hand the imperative to invest in a transportation system that will continue to grow our nation’s economy, create jobs, and enhance U.S. competitiveness; on the other hand, the imperative to come to grips with the nation’s short- and long-term fiscal problems, including especially the federal treasury’s unsustainable and still growing level of debt. In short, it’s not that our political leaders don’t agree that transportation is important or that infrastructure investments are needed; rather they can’t agree on whether or how to fund those investments given the current budget situation.

This massive clash is exacerbated by other tensions noted in the report. A Rockefeller Foundation poll found that while 80 percent of voters agree that transportation improvements “will boost local economies and create millions of jobs” fully 71 percent of voters “oppose an increase in the federal gas tax with majorities likewise opposing a tax on foreign oil, the replacement of the gas tax with a per-mile-traveled fee, and the imposition of new tolls to increase federal transportation funding.” So we the voters want transportation investments yet oppose all the tools that enable such things.

The report notes that some of this can be attributed to public distrust of government, which isn’t helped when pinheaded bureaucrats burn up hundreds of thousands of dollars on a party. However, this is profoundly skewed and unfair reasoning. First of all, there’s a big difference between spending and investment. Senator Whitehouse (D-RI) spun an analogy to illustrate this at a hearing on transportation last July: If a family pays to repair a leaky roof, it’s an investment given the long-term benefits, but a trip to Disneyworld is on the other hand mere spending. The other thing to remember, as former Transportation Secretary Mineta noted recently, is that DOT has a pretty good track record when it comes to spending. The famed “bridge to nowhere,” after all, was a Congressional earmark. And such earmarks are now a thing of the past (another silver lining in this era of dramatic fiscal constraints), which the Miller Center report notes is something that should be publicized more to help rebuild confidence in transportation.

To break through the skepticism and gridlock, the report recommends a new communications strategy with four main components:

- A positive, forward-looking tone that frames the transportation debate around issues of economic growth, jobs, and U.S. competitiveness, combined with quality of life.

- A well-defined but flexible campaign plan that is keyed to the rhythms of an election year and to important events in the transportation calendar.

- A focus on building broader engagement through effective, targeted use of traditional media and social media.

- A concerted effort to link local transportation investment opportunities and benefits to national-level policy decisions.

This is a solid strategy, with two challenges. First, it will require resources to implement. Second, it needs to get off the ground quickly, particularly if transportation is to be an issue on Congressional and Presidential campaign trails (Building America’s Future already organized efforts to raise its profile in New Hampshire and South Carolina this year).

The bottom line is that the Miller Center is spot-on when it proposes a new communications strategy. Technical analysis of transportation problems? Got ‘em. Policy reform proposals? Got even more of those. What we have here is a failure to communicate. Time to get to work on that.