This post was co-authored with Noah Lerner

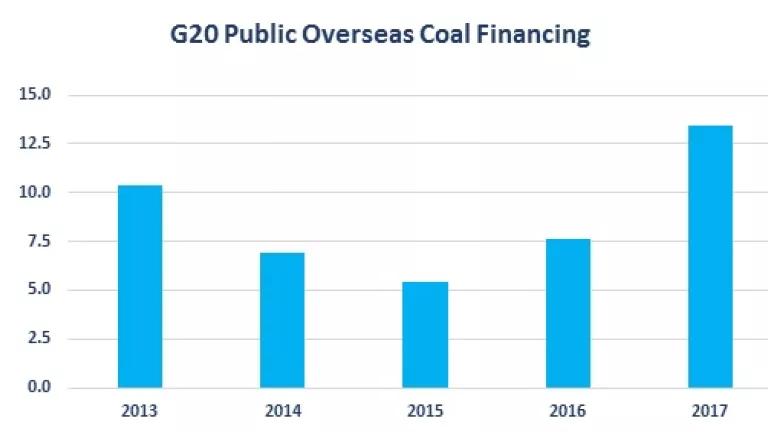

In 2017, financing from G20 governments for overseas coal projects reached a five-year high, totaling at least $13 billion in loans, credits, and guarantees. This financial support for coal projects directly undermines G20 climate commitments and ignores the reality that a rapid coal phase out is needed if the world is to reach the 1.5 degree temperature goal under the Paris Climate Agreement. This is the second year in a row that G20 public financing has increased for coal power projects in foreign countries.

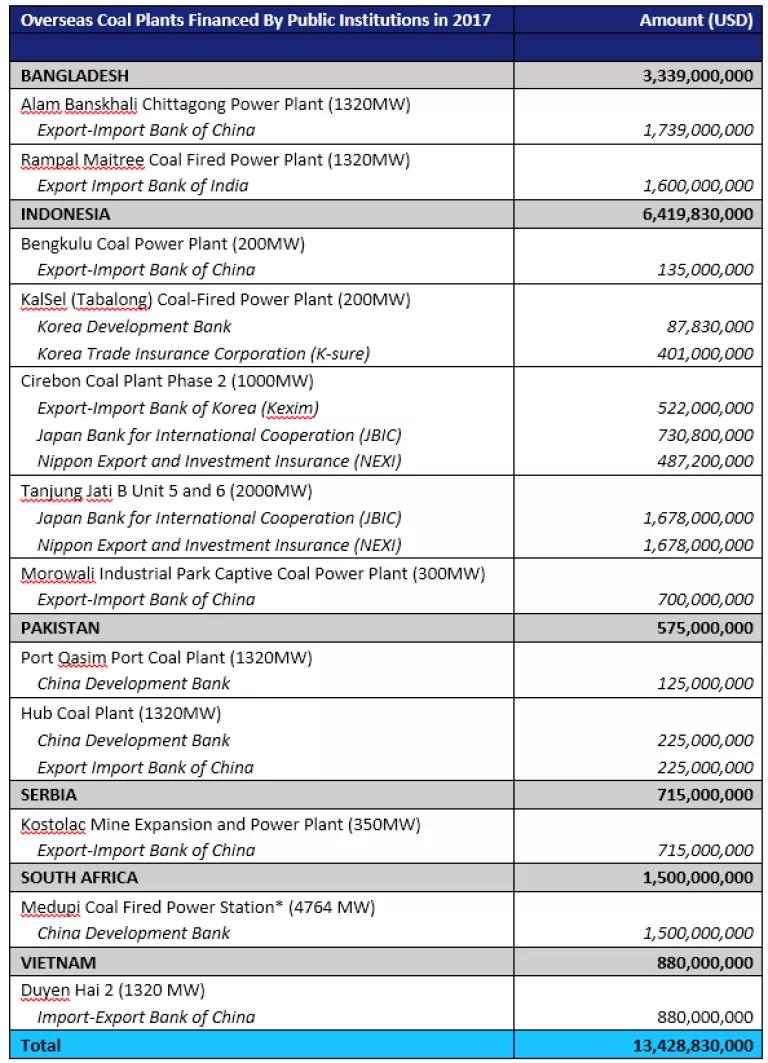

G20 public financing here refers to financial backing from government export credit agencies, like Japan Bank for International Cooperation, development banks, like China Development Bank, and government insurance entities, like Korea Trade Insurance Corporation. Public financial support is given to benefit domestic companies who are involved in projects abroad—for example, in 2017, Japan Bank of International Cooperation provided a $730 million dollar loan to enable Marubeni, a Japanese company, to develop the 1000 MW Cirebon 2 Coal Power Station in Indonesia. Public financial support can take the form of loans, guarantees, export and import credits, grants, and equity financing.

Asia’s Largest Economies Continue to Finance Overseas Coal

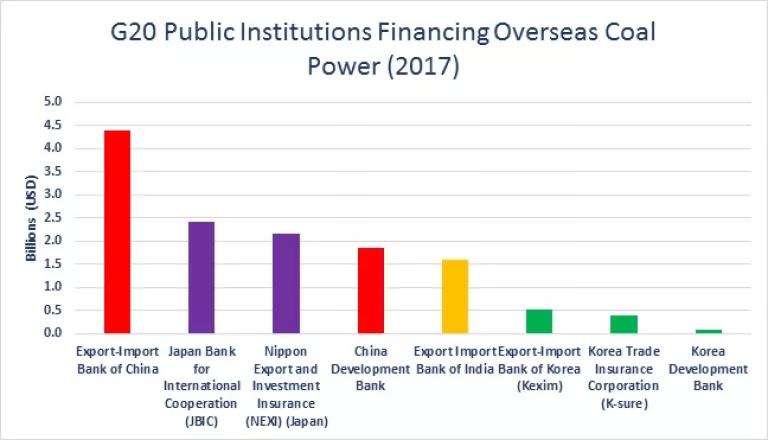

G20 public financing for overseas coal projects in 2017 was driven by financial institutions from four countries: China, Japan, India, and Korea.

It is important to note that, because some financial institutions such as those of Germany and China fail to disclose financing information, this may be an underestimation of total public coal financing.

Japan, China, and Korea have been major public financers of overseas coal power projects over the past few years. As our recent report, “Power Shift: Shifting G20 International Public Finance from Coal to Renewables” shows, from 2013-2016, public financing from these countries for overseas coal power projects has far outweighed public financing of overseas renewable energy projects.

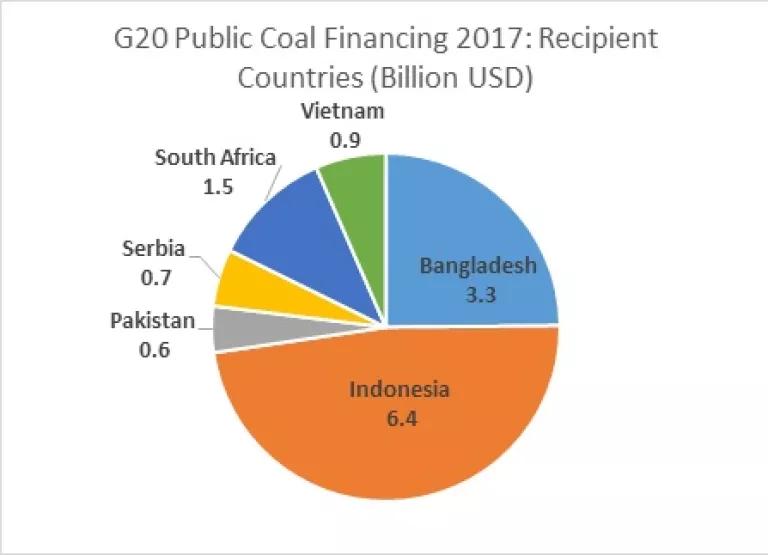

Main Recipient Countries: Indonesia and Bangladesh

The majority of G20 public financing for overseas coal projects in 2017 went to Indonesia (6.4 billion USD) and Bangladesh (3.3 billion USD). These two countries were also the largest recipients of G20 public coal financing in 2016, as summarized in our blog last year. This trend more broadly reflects the status of Southeast Asia and South Asia as the two regions most at risk of a major coal power buildup (see this overview of the remaining global coal power pipeline).

Funding the Dirtiest and Riskiest Energy Investments

While overseas public financing only accounts for a portion of total global financing for coal power projects, the support of government-led financial institutions often enables additional commercial and private financing by lowering investor risk.

In 2017, G20 public financial institutions financed at least 11 overseas coal power projects with a combined installed capacity of over 10.5 gigawatts, equivalent to Spain’s entire coal power capacity. And these projects were big—9 of them were over 1000 megawatts. To put that in context, to date, only two solar farms have been built with an installed capacity of 1000 megawatts or above.

* China Development Bank helped to refinance this project in 2017, but Medupi secured financing before 2011 to start construction.

Local Communities Lead the Fight Against Coal

Many of the publicly financed coal power projects that secured financing in 2017 have long been delayed by controversies and resistance. That there were not more coal power projects that secured financing in 2017 is in part a testimony to the impact of local grassroots and advocacy groups who have fought against coal power project development at each step of the process.

In Indonesia, the environmental permit of the Cirebon II coal power project was revoked in April 2017, just a day after financial documents were signed by the project’s Japanese and Korean financial backers. A separate proposed coal power project in Indonesia, the 2000 megawatt Indramayu Coal Power project, backed by Japan International Cooperation Agency, has also had its environmental permit revoked in response to a lawsuit by a local NGO. Coal power projects were dealt a further blow in October 2017, when Indonesia’s Energy Minister stated that Indonesia will not approve any new coal-fired power plants on the main island of Java, instead prioritizing renewables and gas.

Local communities are resisting not just the pollution, but also the bad economics of the coal industry. A coalition of Indonesian NGOs under the name, “Break Free from Coal,” is lobbying the Indonesian government to stop the development of nine planned coal power projects, worth $26 billion dollars, arguing that the addition of 13 gigawatts of coal power would cause a massive oversupply of electricity capacity, posing a significant economic burden to Indonesia’s taxpayers. In the Philippines, a similar study found that the nation’s proposed $21 billion dollar investments in 10 gigawatts of new coal power would saddle taxpayers and pose a serious risk to Philippine’s financial sector. In order to address the high price of coal, the Philippines government in December passed a significant increase in the coal tax, from the current US $0.20 per ton to $3 per ton in 2020, in order to drive investments in renewable sources of power that can provide cheaper, cleaner electricity than coal.

Communities are also fighting to save fragile ecosystems and historic cultural landmarks. The proposed 1050 MW Lamu Coal Power Station in Kenya would be built near the Lamu UNESCO world heritage site. The project had been in planning since 2013, and could receive public financial backing from the African Development Bank. However, the project’s progress has been slowed by local civil society groups, who are challenging the legality of the project’s environmental and social impact assessment. Local opposition has attracted global attention to the proposed Lamu Power Station; recently, even the European Union has weighed in, advising Kenya to drop the project.

Worldwide, there are dozens of other coal power projects that are being stopped by civil society groups and out-competed by cleaner energy alternatives. In Egypt, for example, several coal megaprojects proposed by Chinese and Japanese companies have been stalled indefinitely, while the country has moved forward on a series of solar projects.

According to EndCoal, from January to July 2017, there were as many gigawatts of coal plants retired as added (1,964 gigawatts to 1,965 gigawatts). More importantly, there were 249 GW of “canceled” projects in 2016, and 377 GW of “shelved” projects.

Public Financing Should Support the Clean Energy Revolution

The International Financial Corporation of the World Bank Group has said that $23 trillion dollars are needed in clean energy technology investment between now and 2030 if the world is to meet the goals under the Paris Climate Agreement. Public dollars should be going into clean, low-carbon investments that ensure long-term sustainable economic growth, not into high-polluting investments that threaten our planet’s future.

There are still over 1.2 billion people living in the world without access to stable electricity. However, the coal industry has propelled a selfish and dangerous myth that coal power is the answer to global energy poverty. This is not the case—new coal power plants cannot provide electricity to the majority of energy-poor communities who live far away from centralized grid infrastructure; instead, the CO2 and other pollution from coal plants only serve to exacerbate poverty. A recent report by the International Energy Agency showed that the path to 100 percent global energy access by 2030 will require mostly investments in off-grid solar and small hydro, with solar and hydro providing 78 percent of new energy access and coal only providing 7 percent of new energy access.

Public financing for coal, the most polluting and greenhouse gas-intensive form of energy, is a reckless use of limited public dollars, which come from taxpayer revenues and other government income. That’s why countries like the UK, Canada and France have already committed to restricting financing for coal power through the Powering Past Coal Alliance. On the other hand, laggards such as the United States and Japan have committed to building even more coal plants abroad (The US Trade and Development Agency, for example, just put out a call for coal projects in emerging markets.)

Even the major G20 public banks that are still financing coal have begun to push forward renewable energy projects—but we urge them to transition faster. Japan International Cooperation Agency provided $553 million dollars to Laguna Colorada Geothermal Power (100MW), the first-ever geothermal project in Bolivia, while the Nippon Export and Investment Insurance covered $47.2 million dollars of insurance for the 98 megawatt Huatacondo Photovoltaic Project in Chile. China’s Sinosure provided $145 million dollars in export buyer’s credit insurance to support JA Solar to export 300 megawatts of solar panel modules to Brazil, while the Export-Import Bank of China stands poised to finance the 300 megawatt Cauchari Solar Complex in Argentina, which will be Latin America’s largest solar park. Last November, China Development Bank also made news, debuting China’s first ever government-backed international green bond, raising 500 million USD and 1 billion EUR in funding to support green projects in Kazakhstan, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.

Financial Institutions Must Accelerate the Transition Away from Coal

In 2017, there was some movement by major financial institutions to shift away from coal and other fossil investments. A report from Unfriend Coal in November 2017, showed that major insurance companies had divested over $20 billion from the coal industry, while French insurance giant AXA made headlines by setting the financial industry’s strictest coal restrictions, quadrupling its divestment of coal after expanding its definition of companies involved in the coal industry. Already, several major commercial banks, including CreditAgricole, Nataxis, and Deutche Bank have pledged to restrict financing to coal power and coal mining projects. According to BankTrack, at least 19 major international commercial banks have placed at least partial restrictions on coal industry financing (see their complete list). In Korea, legislative proposals are gaining traction to limit public financing for coal power projects, as legislators question Korea’s public finance institutions about why taxpayer money is being used for risky and highly polluting coal projects in Indonesia and Vietnam.

It is time for all major financial institutions to stop financing coal and other fossil fuel investments, and to shift investments to clean energy and energy efficiency. We can see with our own eyes the air and water pollution, as well as disasters such as hurricanes and wildfires intensified by climate change—that result from our over-reliance on burning coal and other fossil fuels. G20 countries should be leading the way and investing public money in clean energy, not coal.

For additional information on G20 Public Financing from 2013-2016, see our report, Power Shift: Shifting G20 International Public Finance from Coal to Renewables