CARB Must Reform LCFS Program to Meet Climate Goals

CARB's Low-Carbon Fuel Standard currently funnels millions of dollars a year to polluting fuels. Will CARB listen to the community voices calling for change?

The Port of Long Beach in Southern California is home to the first of several heavy-duty electric truck charging depots in the state.

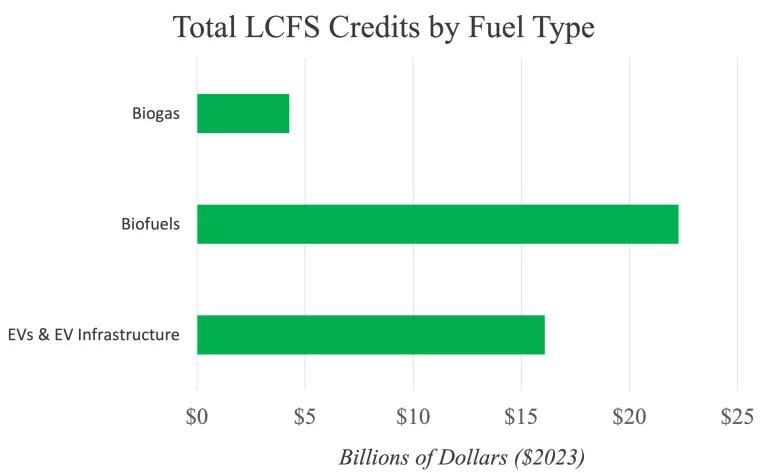

The California Air Resources Board (CARB) will soon update the Low Carbon Fuel Standard (LCFS) Program: one of California’s largest sources of funding for clean transportation. The state is transitioning to zero-emission vehicles to meet climate goals, with targets of 100 percent electric vehicle (EV) sales for passenger vehicles by 2035 and 100 percent zero-emission heavy-duty truck sales by 2036. Yet, between 2011 and 2022, the LCFS channeled more than $5.8 billion ($2023) towards factory farm gas and crop-based biofuels— polluting fuels that CARB’s own Scoping Plan finds are not significant, long-term decarbonization solutions for the transportation sector. CARB must reform the LCFS to bring California’s ambitious climate targets within reach.

What is the Low Carbon Fuel Standard?

Established in 2009, the LCFS Program aims to reduce the carbon intensity (CI) of California’s transportation fuel pool by at least 20% by 2030. The Program sets annual CI standards for transportation fuels, which decline over time. Fuels above the standard generate deficits, while fuels below the standard—such as EVs powered by clean electricity—generate credits.

As a transportation decarbonization program, the LCFS should support the most promising technologies aligned with California’s long-term climate and air quality goals. But in practice, flawed carbon intensity scoring has led to polluting fuels—including biogas and biofuels—receiving more overall LCFS credits than clean electric solutions.

LCFS funding by fuel type (2011-2022), based on data from UC Davis LCFS data visualization tool.

Source: NRDC

Environmental justice organizations have long called on CARB to change these practices. The clock is ticking for the Board to respond.

Factory Farm Gas Wins Big in the LCFS

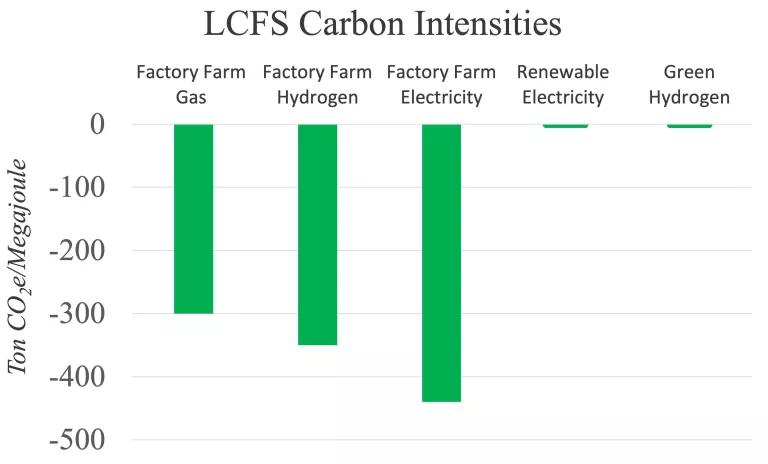

Factory farm gas—that is, biogas that is captured in digesters at big, polluting livestock operations—is a combustion fuel that receives millions of dollars in LCFS funding, at the expense of communities and the climate. Under the current scoring system, fuels derived from factory farm gas receive outsized CI scores that range from negative 300 to negative 400 tons CO2e/MJ, resulting in significant subsidies: Since the Program’s inception, factory farm gas has raked in more than $1.26 billion ($2023) from the LCFS.

Factory farm gas receives such a low CI score because the LCFS assumes that manure methane from factory farms would otherwise be released into the atmosphere if not “captured” in digesters, and it gives the transportation sector credit for cleaning up the pollution of the agricultural sector. Yet, to meet economy-wide climate targets, California cannot accept methane venting as a baseline. Instead, CARB must meaningfully address agricultural emissions in their own right – including enteric emissions from livestock, which are responsible for up to 30 percent of global methane emissions but are not addressed by any state programs today.

Factory farm gas has a negligible role to play in decarbonizing transportation, and, according to California legislative committee analysis, digesters may not be the most cost-effective strategy for reducing manure methane from farms. Yet, the LCFS’s avoided methane crediting wrongly assumes that the transportation sector should be responsible for making use of waste products from the livestock sector. This distorts the LCFS Program.

Outsized incentives for factory farm gas particularly benefit large, concentrated livestock facilities, which pollute the air and water of the communities who live near them. They also undermine the LCFS program’s ability to fund clean technologies, like EVs powered by renewable electricity. As shown below, the lowest possible CI score for renewable electricity is zero—placing it on an uneven playing field with factory farm gas and stifling the deployment of EVs and EV charging infrastructure.

Approximate carbon intensities under current LCFS CI scoring system, based on modeling from Stanford University's Climate & Energy Policy Program.

Source: NRDC

This flawed CI scoring also impacts the type of hydrogen incentivized by the LCFS. Under the current system, a refinery can produce polluting hydrogen from fossil gas, purchase LCFS credits for factory farm gas from anywhere in North America, and then sell their hydrogen on the market with a negative CI. Meanwhile, green hydrogen produced from solar electricity achieves a minimum CI of zero. This directly undercuts state efforts to scale the production of green hydrogen, while continuing to subsidize pollution that harms fence line communities most impacted by refinery pollution.

Proponents of the current scoring system for factory farm gas argue that the LCFS is taking care of emissions from the agricultural sector. But as a transportation fuels program, the LCFS should drive California towards an all-electric transportation future – not waste money on expensive factory farm gas digesters that have little to no role in the clean transportation future. Instead, CARB should adopt separate, dedicated policies to meaningfully address the air and climate emissions from factory farms—such as directly regulating emissions from the agricultural sector.

CARB Must Limit Crop-Based Biofuels to Avoid Disastrous Outcomes

The LCFS also supports biofuel production at potential significant cost to the climate, the food system, the environment, and communities living near refineries. Recently, two Bay Area refineries, both located in disadvantaged communities of color, were issued permits to convert to produce renewable diesel at a massive scale, with both operators justifying the conversion based on the LCFS. These conversions are consistent with the larger recent trend of biomass-based diesel (BBD) growing steeply as a share of California’s alternative fuels market, from 1% to 50% between 2011 and 2021. These refineries pollute nearby communities, and trucks that burn biodiesel pollute communities living near busy highways across California.

Producing biofuels at this scale also has huge land use and carbon impacts that are not accounted for in current LCFS CI calculations. Expanding production requires the clearing of new land to grow soy, corn, and other crop feedstocks. It also leads to an increase in palm oil production to backfill the oils that are diverted to biofuel production, leading to the destruction of rainforests in the Amazon and Indonesia that are vital to planetary health. CARB must place a cap on crop-based biofuels and update the flawed carbon intensity scoring for these fuels to avoid unintended harmful outcomes.

California’s Transportation Future is Zero-Emission

California is committed to achieving 100 percent electric vehicle (EV) sales for passenger vehicles by 2035 and 100 percent zero-emission heavy-duty truck sales by 2036, with EVs and EV infrastructure playing a key role in the transition to a clean transportation sector. CARB’s Scoping Plan finds that meeting California’s transportation goals will require the state to increase the number of EVs on the road by 30 times over the next 20 years, while CARB’s Advanced Clean Fleets rule requires the state to deploy approximately 1.7 million zero-emission trucks by 2050.

Addressing the carbon accounting flaws in the LCFS would boost the amount of funding available for EVs, in alignment with CARB’s own policies. For example, Stanford University’s Climate and Energy Policy Program finds that ending “avoided methane” crediting for factory farm gas in 2024 would more than double the amount of LCFS incentives that go towards EVs between now and 2030, from $15 billion to $34 billion.

In addition to correcting the flawed CI calculations for polluting fuels, CARB should increase the LCFS program’s focus on transportation electrification, particularly for low-income Californians. Utility programs funded by LCFS credits should dedicate resources to low-income households and communities, and the LCFS should expand incentives for medium- and heavy-duty EV charging and electric vessels, aircraft, and off-road equipment.

Andrew Roberts on Unsplash

The LCFS can be a tool for driving forward the transition to a cleaner, healthier, and safer transportation sector—but only if CARB acts to ensure that LCFS pathways are aligned with California’s climate and environmental justice priorities.

CARB will update the LCFS over the course of the next year. You can read NRDC’s letter urging CARB to reform the LCFS program here.