China Fights Back Against Airpocalypse: A new air pollution initiative that just might work!

There is something new, exciting, and very different that went into effect New Year’s Day in China to address that country’s terrible pollution problems that has not (to my knowledge) garnered much attention. It is a massive public reporting initiative. Specifically, the Chinese central government has just required roughly 15,000 of the country’s biggest factories to publicly report their air emissions and wastewater discharges continuously – (every hour for air emissions and every two hours for wastewater every day of the year) - on the internet. ( Measures for Self-monitoring ). The list of factories is here ( The List of National Key Company for Monitoring ) A few major provinces, most notably including Shandong, Zhejiang, and Hebei, jumped on this edict right away and have begun posting the information, and others hopefully are on their way. (See, for example, http://58.56.98.78:8801/webgis_wry/webgis/default.aspx (Shandong) and http://app.zjepb.gov.cn:8089/nbjcsj/ (Zhejiang)) .

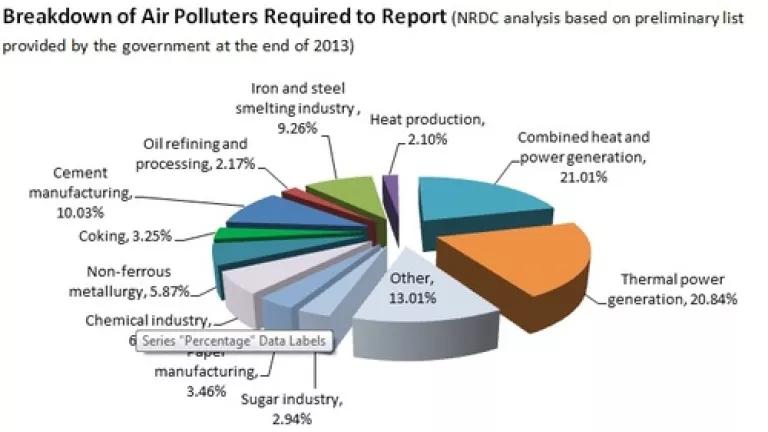

An NRDC analysis of the preliminary list of 15,000 (a little over 4000 of which will report their air emissions) shows that the most important types of factories in the most polluted places are on the hook to report. Power plants, cement kilns, smelters, and iron and steel mills are well represented, along with a few other of the usual suspects (chemical manufacturing, pulp and paper, etc). (See figures in Breakdown of Air Polluters for more analysis.)

Distribution of industries required to report their air pollution:

The Chinese Environmental NGO, Institute for Public and Environmental Affairs (IPE at http://www.ipe.org.cn/En/ ) will be releasing a report on January 14 with more detailed discussion of these developments.

This reporting initiative, which takes full advantage of the internet and the inter-connectedness of the modern world, puts China clearly in the lead on environmental reporting internationally. No country, to my knowledge, has anything like it.

I’m going to stick my neck WAY out here and say: this reporting initiative is the biggest thing China has done to address its pollution problems to date, and, based on our experience in the U.S., the most likely to succeed. Why? Never underestimate the power of information.

Those of us tracking environmental issues in China over many years are familiar with the usual government responses to the country’s heavy air pollution problem: typically well-crafted laws and edicts are issued by the central government that direct the country to reduce coal consumption, limit the number of cars on the road, shutter problematic steel mills, etc. However, on the ground, implementation and enforcement are then lax. Provincial and local government officials lack the capacity and/or political will to follow the directives, and business as usual tends to prevail. As one of my favorite expressions in China says: “The sky is high, and the emperor is far away” – from a proverb that has come to generally mean that central authorities have little influence over local affairs. (The expression is often used as a veiled reference to corruption.)

But the provision of real time public information on pollution emissions and discharges could change all of that.

While we have nothing like this real time monitoring data in America at the moment, our country has experienced the impact that far more limited reporting can make. The United States first headed down the public reporting road way back in 1986, with the creation of our Toxic Release Inventory (TRI), which is still in use today. It is a one-time annual event, and it is based on industry estimates where measurements are not in place. The TRI looks like – and in fact is – something that was developed and came of age in the mid to late 20th century. It, too, was initially a ‘sleeper” here, and few if any of us thought it would have much impact. But in less than a decade, TRI reduced releases of the hundreds of chemicals on the inventory by nearly 50% simply by publicly “outing” problem places. Scholars today consider it to be one of the most successful programs in the US EPA history. (Effectiveness of TRI ).

Why did simple disclosure drive environmental improvement here, even with much more limited access to the data back in the 80’s, and even in a mature environmental regulatory system of the United States at that time? Public information empowered ordinary people and NGOs to effectively pressure polluters to change. They used it to identify the biggest contributors to their local pollution problems, to check a facility’s emissions against permit records, and to assess the adequacy of existing permit limits – which informed their advocacy and focused their work. Government officials made good use of the data as well, because it enabled them to compare emissions of similar facilities across the country, to identify top priorities for clean production audits within their state or locality, and to create worst-first focused action plans. Perhaps most surprisingly of all, the information proved useful and influential to factory managers and CEO’s themselves in America; it enabled them to benchmark their performance against the competition and see where they were falling short. Often factories were shocked to see that they were the biggest emitter of a certain pollutant in their state or region, or even in the country, and this insight motivated them to take action, even where their emissions were legally allowed.

The simple embarrassment of being on the top of a public list of big polluters inspired industry to take action. No one would have thunk it.

And don’t forget: our TRI was born long before smart phones, social media, or even the internet! As I recall, EPA’s initial data disclosures were at first in hard copy print, and we had to wait for the Agency to issue a report and mail it to us. The real-time readings and instantaneous nature of discharge and emission data being provided in this program in China today -- and the inevitability that soon its citizens will be able to receive such salient information on their smart phones -- can only accelerate the impact disclosure like this will have.

Of course, it is early in this new game. There is still quite a long way to go before this new system is fully up and running. Many provinces, like Tianjin, have not yet commenced this reporting, and I sure hope they do not lag too far behind. We are also missing important types of monitoring data, particularly data on particulate matter emissions from many sources; such data is of course of key interest to the public health community. We hope that in the coming months, the program further matures and becomes more comprehensive and even more informative.

To date, Chinese citizens concerned about air quality have been limited just to taking steps to avoid exposure: buying face masks and air purifiers and leaving town when possible. This new public information program will enable them (as well as environmental officials) to address the pollution problems at their source.