COP27: World Leaders Must Raise Climate Ambition

As we move closer and closer to climate catastrophe, global climate action has never been more necessary.

The Red Sea Reef in Ras Muhammad National Park near Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt

As we move closer and closer to climate catastrophe, global climate action has never been more necessary.

World leaders will be meeting in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt, in November to try to accelerate the global response to the widening climate crisis at an extraordinary moment. Seldom has global climate action been more difficult. Never has it been more necessary.

President Joe Biden is working to restore U.S. climate leadership by cutting carbon pollution at home and pressing to increase climate assistance for vulnerable communities and countries abroad.

What’s needed in Sharm El-Sheikh is concerted action—especially from the United States and other countries that have done the most to cause the climate crisis—to advance equity, strengthen accountability, and raise global ambition.

Although the headwinds are strong, the case for climate action is far stronger, and never more so than now.

A landscape of cascading crises

The global economy is still struggling to recover from the COVID pandemic, with inflation, persistent supply chain disruptions, and economic recession bearing down on people and governments. Russia’s brutal war in Ukraine has caused cascading crises—security, humanitarian, energy and food—across the region and around the world.

At the same time, it’s been a year of no sanctuary from the mounting devastation of climate change.

Floods unlike any on record displaced or otherwise impacted some 33 million people in Pakistan in a matter of days. Record-breaking heat dropped water levels in the Yangtze River, the breadbasket to one in every five people on earth, and slowed water flow to a trickle in places. Hurricane Ian killed at least 114 people in Florida, the American West is baking through its worst drought in 1,200 years, and wildfires have burned enough U.S. land this year to cover the state of Vermont.

The world is reeling. Leadership is being tested. Emergency measures are falling short.

The climate talks in Sharm El-Sheikh can’t fix all of this. However, leaders there can and must make real progress, both to confront the rising toll of climate change and to address the landscape of widening crises. Far from being a reason to hit pause on climate solutions, the welter of global crises only strengthens the case for action now.

A camp for displaced people on the outskirts of Dollow, Somalia, which was on the verge of famine—a sign of the dire consequences of drought—in September 2022

Energy, inflation, food, and climate

What’s called the global energy crisis hasn’t impacted wind and solar power. Both are thriving. Russia has sparked a crisis in fossil fuels, pummeling fragile economies with price and supply shocks. The answer isn’t to deepen our dependence on coal, oil, and gas. The solution is to break free of these fuels, the perpetual cycles of disruption they bring, the riches they divert to belligerent petro-states, and the climate hazards and harms they cause.

Investing in renewable power is one of the best ways to diversify energy sources and promote energy security on a global scale. The Kremlin can't weaponize the wind and sun.

Inflation, too, is being fed by fossil fuels, as oil and gas prices get rolled into the production and shipment of goods, even as oil and gas industry profits soar—a staggering $4 trillion this year alone, which is double that of last year’s levels.

Increased wind and solar power will help bring prices down. And clean energy investment—on track this year to hit a record $815 billion worldwide—is driving global growth and job gains, a cushion against recession.

Food scarcity is made worse by climate change. Croplands are turning to desert in parts of China, Kenya, and even Kansas in the United States. Pakistan lost millions of acres of rice, cotton, and other crops this year when flooding put a third of the country under water. Across the Horn of Africa, the worst drought in 40 years has pressed 22 million people to the brink of starvation. And, since much of the world’s fertilizer is made from natural gas, price hikes for that fuel are driving up costs for farmers, forcing many to scale back, charge more, or both.

These and other climate impacts are falling disproportionately on vulnerable households, communities, and countries. That’s why climate progress in Sharm El-Sheikh must begin with climate equity.

Addressing a grave and self-evident injustice

It’s a grave and self-evident injustice that many of the countries paying the highest price for the climate crisis have done the least to cause it and lack the resources to cope with its consequences.

A handful of large emitters—China, the United States, Russia, and the European Union—together account for 63 percent of the climate-wrecking carbon pollution that’s accumulated in the earth’s atmosphere from the burning, over time, of coal, gas, and oil.

Ten countries that are most acutely vulnerable to climate hardship and hazard—Bangladesh, Pakistan, India and seven others—have together contributed 1 percent of the pollution. For the people of these countries to be forced to pay a price they can’t afford for a crisis they didn’t cause is patently unjust. The nations that produced the climate pollution, enriching themselves in the process, have an obligation to address this injustice.

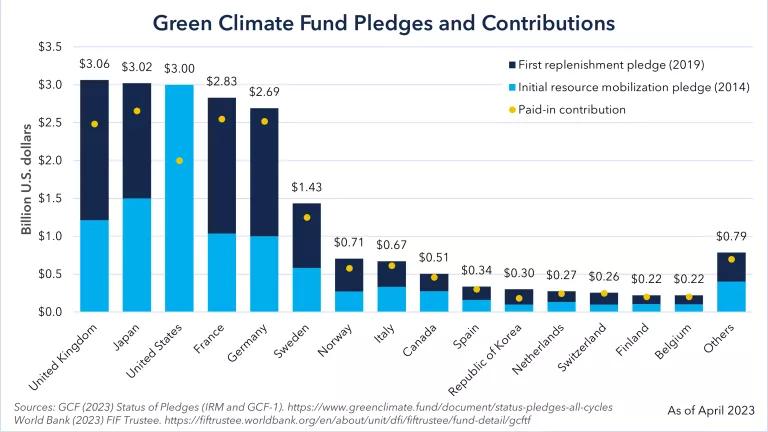

Wealthy nations pledged to mobilize $100 billion a year, by 2020, to help developing countries adapt to climate consequences and invest in clean energy. The target has yet to be met, with developed countries coming up $17 billion short in 2020.

The United States is largely to blame. President Biden’s call for $11 billion a year for this purpose would finally help to close the gap. That request is now before Congress, and legislators must rise to the moment.

The mounting costs of loss and damage

There are climate costs, though, that no amount of adaptation and clean energy investment can address. Frontline countries need help to address these high and rising costs.

Over just the past two decades, climate change has stripped away an estimated $525 billion in economic value from 55 low-income countries. That’s one-fifth of the total wealth created in these countries during that period, cutting a full percentage point, on average, off annual GDP growth.

Together, the governments of these countries were struggling to service a total of nearly $700 billion in external debt, even before the additional economic stress of the global COVID pandemic.

Countries are having to choose between health care and education for their children and servicing burdensome debt, while climate disasters they’ve done nothing to cause devastate their communities and bleed them of generational wealth. That’s not sustainable—and it’s not just.

What’s needed are financing arrangements that provide sustained relief to countries for climate loss and damage that have already occurred or are baked into the climate future. This is for countries that have lost arable land to soaring temperatures and rising seas; people who have watched clean water supplies vanish as glaciers melt; and communities struggling to survive in a vortex of raging storms, floods, and drought.

This important work won’t be completed in Sharm El-Sheikh, but there must be a concrete framework put on the table that sets short-term deadlines for establishing solutions. This isn’t charity. It’s about rich nations shouldering the responsibility for the loss and damage their actions have inflicted on others. It is, in every sense, a debt that large carbon-polluting nations owe to lower-income people around the world.

Victims of heavy flooding from monsoon rains in the Qambar Shahdadkot district of Sindh province, Pakistan

Fareed Khan/AP Photo

Delivering on promises already made

Next, these talks must focus on accountability—delivering on promises already made.

At the landmark Paris climate talks in 2015, global leaders pledged to limit global warming to well below 2 degrees Celsius (3.6 degrees Fahrenheit) and as close as possible to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit) below preindustrial levels. At global climate talks last November in Scotland, world leaders affirmed the 1.5-degree goal, noting that warming above that level would trigger catastrophic climate consequences worldwide.

Under current policies, however, the world is on track for warming of 2.8 degrees Celsius (5 degrees Fahrenheit), the United Nations reported in late October, concluding that there is, currently, no credible pathway to meeting the 1.5-degree goal.

That is unacceptable. World leaders, beginning with those representing China, India, the European Union, the United States, , and other large emitters, must deliver on the policies required to hold warming to the agreed-upon limit of 1.5 degrees Celsius.

Last November, President Biden went to climate talks in Scotland on the winds of a bold pledge: to cut U.S. greenhouse gas emissions by 50 to 52 percent by the end of the decade. He goes to Sharm El-Sheik in November with the strongest U.S. climate action in history to do precisely that.

His job now is to make sure the $369 billion in clean energy investment contained in the Inflation Reduction Act he signed into law in August is robustly implemented.

The federal agencies most responsible for that—the departments of Agriculture, Energy, Transportation, Treasury, and others—must make sure every dollar contributes to the carbon reductions, job creation, and equity gains the country so urgently needs.

This is strategic investment that will reach beyond U.S. shores, helping to drive innovation and economies of scale that create new solutions and drive down costs for everyone, as global clean energy investment reaches into the tens of trillions of dollars in the decades ahead.

Beyond that, Biden must use the authority he has under existing law to write rules and standards to help cut the carbon pollution from our cars, trucks, and dirty power plants; make our homes and workplaces more efficient; reduce leaks of climate-warming methane gas from oil and gas operations; and keep investors apprised of corporate climate risk.

The clean energy investment in the Inflation Reduction Act positions the country to cut its greenhouse gas emissions by 40 percent by 2030. The rules and standards listed above can raise that figure to about 47 percent. State and local actions can combine with these efforts to hit the target Biden set: emissions cuts of 50 to 52 percent below 2005 levels, by 2030.

That’s the kind of follow-through required of the United States and other large carbon-emitting countries to provide the accountability we need to confront the climate crisis.

We are seeing strong evidence on the ground that China will meet its target to reach peak carbon emissions by 2030 and, possibly, before then. China, though, is not without challenges, including a short-term increase in coal use, in part because severe drought reduced electricity production from large hydroelectric facilities this summer, just as record heat waves drove up demand for electricity to cool workplaces and homes.

China continues to lead the world in clean energy investment, totaling $266 billion last year, which is 43 percent of the world total. There’s more to be done, though, by China and all major emitters to meet its carbon reduction goals.

Similarly, India is on track to meet its two key goals—to reach 50 percent of its electricity generation capacity without fossil fuels by 2030, and to cut carbon emissions 45 percent by then as a share of economic output, compared to 2005 levels. This year, India enacted legislation that sets efficiency standards for residential buildings and establishes a domestic carbon credit market. In addition, India is expanding wind and solar power at one of the fastest rates in the world. Needed now: increased investment and technology to keep the forward progress moving.

From left: Massachusetts representative Jake Auchincloss, Massachusetts senators Ed Markey and Elizabeth Warren, Special Envoy for Climate John Kerry, and President Joe Biden, who warned about climate change during his speech at the former location of the Brayton Point Power Station in Somerset, Massachusetts

Brendan Smialowski/AFP via Getty Images

Raising climate ambition

Finally, world leaders need to raise climate ambition.

As the new U.N. report makes clear, current policies are falling well short of what’s needed to avert climate catastrophe. Globally, we’re on track for emissions cuts of between 5 and 10 percent by 2030, which is far short of what’s needed to avert full-on climate catastrophe within our lifetime.

The science is clear. We must cut global carbon pollution in half by 2030, and stop adding it to the atmosphere on net by 2050, in order to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 degrees Fahrenheit).

At that level, to be sure, the world will continue to experience climate disasters and ongoing damage and loss. We’re on track, though, for far worse. “Policies currently in place, without further strengthening, suggest a 2.8-degree Celsius hike,” the U.N. report states.

That would be catastrophic beyond our imagining.

At that level of warming, most of the earth’s coral reefs would perish from heat. Hurricanes would gain force beyond anything we’ve known. Sea rise would be measured not in inches but in feet. There would be species collapse en masse. Arctic ice and glaciers melted. Crippling heat waves and prolonged drought would become the norm. Life itself would become a constant struggle across much of the planet as people face an unending chain of destruction and risk that threatens to overwhelm the coping capacity of even the richest of nations, while leaving lower-income countries utterly ravaged.

We simply cannot live like that, nor force it upon our children. At Sharm El-Sheikh, world leaders must rally around the 1.5-degree Celsius limit they committed to in Paris in 2015 and reaffirmed last year in Glasgow. And they must commit to the policies and investments that will be required to hold the line on warming there.

The world’s largest carbon emitters—starting with the United States, the European Union, China, and India—must raise their carbon reduction targets and accelerate the shift to clean energy, low-emissions vehicles, and modern power grid and storage systems. And the rich nations must help other nations to do the same.

We must work, all of us, to protect and restore forests and wetlands, and strengthen their capacity to capture carbon from the atmosphere and lock it away in healthy soils. We must promote climate-smart agriculture. We must make our homes, workplaces, and cities more efficient, more livable, and more equitable. And we must protect and assist the world’s most vulnerable people from frontline climate hazards and harms.

Global talks on climate, like international meetings on anything, were never meant to be a cure-all. In the years since the breakthrough 2015 climate talks in Paris, though, these international climate talks have created enormous momentum for progress and change. We must build on that momentum in Sharm El-Sheikh now, more than ever.