Now Is the Time to Go All In on California Water Reuse

The state now has the country’s most robust, comprehensive water reuse regulations—and it must commit to investing in water reuse facilities for a more climate-resilient future.

Santa Monica's Sustainable Water Infrastructure Project advanced treatment water recycling plant captures stormwater, urban runoff, and wastewater for reuse.

City of Santa Monica

On December 18, the California State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) unanimously approved direct potable reuse (DPR) regulations. Wastewater treated to meet the new DPR regulations can be served directly to customers without a temporal, spatial, or mixing buffer. Now California has the most comprehensive water reuse regulations in the nation and, on paper, regulations that protect public health while providing the public, agriculture, and industry with a reliable source of water.

Because everyone bathes and flushes toilets, recycled water is more reliable than climate-vulnerable imported water and highly variable stormwater sources. And unsustainable groundwater management has led to decreased reliability in many groundwater basins; plus, locations like San Diego don’t have ample groundwater resources.

Water reuse in California has been modestly successful over the last few decades with the Orange County Water District producing more than 140,000 acre feet per year (AFY) of advanced treated water that is largely used for groundwater augmentation through its Indirect Potable Reuse (IPR) program.

Currently, California recycles approximately 750,000 AFY, far short of the SWRCB’s 2009 water reuse plan targets of 1.5 million AFY of water reuse by 2020 and 2.5 million AFY by 2030. Governor Gavin Newsom’s administration greatly reduced those targets as part of the California’s Water Supply Strategy: Adapting to a Hotter, Drier Future, with targets of 800,000 AFY of water reuse by 2030 and 1.8 million AFY by 2040. These targets were reduced for many reasons, including the lack of significant progress on major water reuse projects in the last 10 to 15 years. But with the passage of the DPR regulations in conjunction with existing IPR regulations for groundwater and surface water augmentation, as well as Title 22 water reuse regulations for largely non-potable water supply needs, the lack of comprehensive regulations can no longer be used as an excuse to maximize water reuse in the state.

However, even with the regulations in place, there are two major hurdles to overcome before California fully embraces its water reuse potential. The first issue is the public perception and media infatuation with the toilet-to-tap concept. For example, when then-councilperson Joel Wachs ran for Los Angeles mayor in 2001, a key part of his platform was opposition to water recycling. He used the toilet-to-tap expression to oppose water reuse as well as the recently completed East Valley Water Reclamation Project that was built to provide IPR water to the San Fernando Valley groundwater basin. Wachs lost in that election, but the damage was done. That completed project cost more than $55 million in the 1990s and was mothballed for decades because of the bad PR from Wach. To this day, Los Angeles only gets about 2 percent of its water supply from recycled water.

Learning from the history and the successful PR campaigns for Orange County Water District recycled water is critical for the water reuse transformation needed to provide the state with a new water supply that builds climate resilience. One way to build consumer confidence is through public outreach and education. Another need is better water-quality data, ideally in real time. Environmental groups—including NRDC, Heal the Bay, the California Coastkeeper Alliance, numerous waterkeepers, Defenders of Wildlife, and Clean Water Action—commented that to provide consumers with the confidence to embrace all water reuse including DPR, there needs to be a robust monitoring program for contaminants of emerging concern (CECs) as well as the use of flow cytometry machines to measure potential pathogens and pathogen indicators in real time.

The public is justifiably concerned about all the new chemicals and pharmaceuticals that can be found in sewage. A monitoring program that demonstrates that multi-staged advanced treatment including reverse osmosis and advanced oxidation/disinfection is preventing all passthrough of CECs in reclaimed water is essential. A few years of demonstrating that there is no significant CEC passthrough in IPR or DPR quality water will boost public support for water reuse. Flow cytometry measures small particles in liquid flow. Predominantly used in the medical field for decades, flow cytometry has been used in some European water reuse facilities as well as in numerous studies on wastewater treatment.

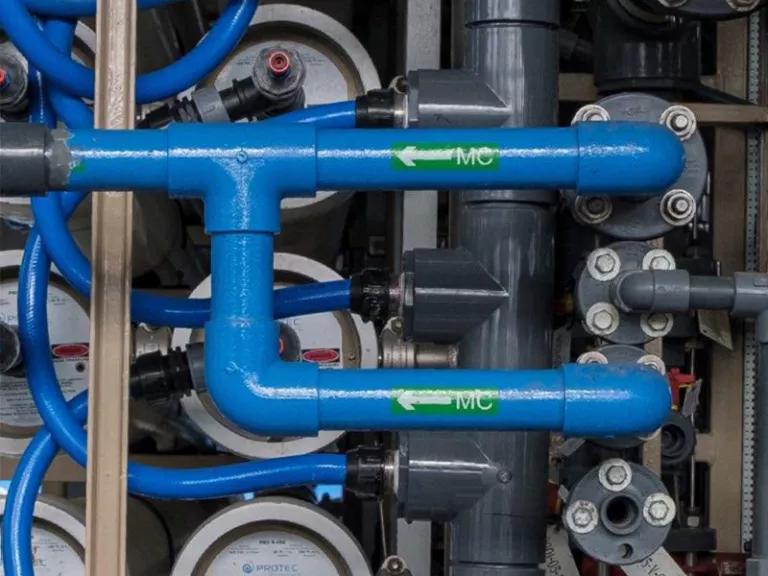

Pipes and reverse osmosis membranes from the Pure Water Southern California pilot advanced treat water recycling facility in Carson.

Metropolitan Water District of Southern California

DPR regulations only require real-time monitoring of total dissolved solids (an indicator of salts that could pass through reverse osmosis membranes), total organic carbon, temperature and pH. This is not adequate to provide the public with the confidence that every drop of water from a DPR water-recycling facility is pathogen-free. Operator error, inadequate maintenance or facility staffing, or even flaws in the wastewater treatment machinery can lead to CEC and/or pathogen passthrough in even the best designed facilities.

Although SWRCB staff emphasized the need for monitoring requirements for CECs and real-time monitoring for pathogen indicators, it did not include more monitoring requirements. The SWRCB board members discussed these issues at length but ended up approving a general requirement for staff to report back to the board in a year to discuss DPR program progress. This will likely include discussion on CEC and real-time pathogen indicator monitoring to provide greater consumer confidence and help ensure that the advanced water recycling facilities are always operating as designed.

Now that California has robust, comprehensive water reuse regulations that will protect public health if facilities comply with the DPR regulations, a major roadblock to water reuse has been removed. Consumer confidence is a barrier that can be overcome with a combination of better monitoring programs, transparent data, and a strong outreach and education program that reaches all potential recycled water users. However, until the state and federal government invest billions of dollars in water reuse in California, the major transformation the state needs will be stymied by the high cost of the water reuse projects and affordability issues, especially for low-income customers.

California has offered modest funding for water reuse over the last decade and the federal government has focused on low interest loans. The investments need to be at least one to two orders of magnitude more than they’ve been to date. For example, Pure Water San Diego, Pure Water Southern California (MWD and the LA County Sanitation Districts), and Operation Next (city of Los Angeles) can produce over 400,000 AFY of new water—nearly enough to provide the annual water needs for Los Angeles. However, the cost of these three projects and the extensive water distribution systems that go with it could be $20 billion or more. As expensive as that sounds, completion of the water reuse facilities will provide water supply reliability and climate and water resilience for Southern California: a growing and dire need.

Locally, Los Angeles has a local water goal of 70 percent by 2035 and the county has a goal of 80 percent local water by 2045, and we can’t meet these climate-driven sustainability goals without major state and federal investment in water reuse. Our climate and water future can’t fall exclusively on the shoulders of ratepayers, especially low-income ratepayers struggling with affordability issues.