California is in the midst of reinventing its energy infrastructure for a number of reasons: massive amounts of clean renewable energy (like solar and wind) are coming online; the state’s second largest nuclear power plant recently retired; and a whole slew of clunky old gas plants are in the process of closing. But that leaves the important question of: How will California replace the energy that was generated by the retired power plants?

First, the state needs to figure out how much energy we are going to need over the next decade. This is called the “energy forecast” and the Energy Commission helped answer that question yesterday when it updated its energy forecast with actual data for 2013. (Which it now updates every year to better coordinate with other state planning processes.) And the good news is: counting on energy savings is the smartest way to plan for our energy future.

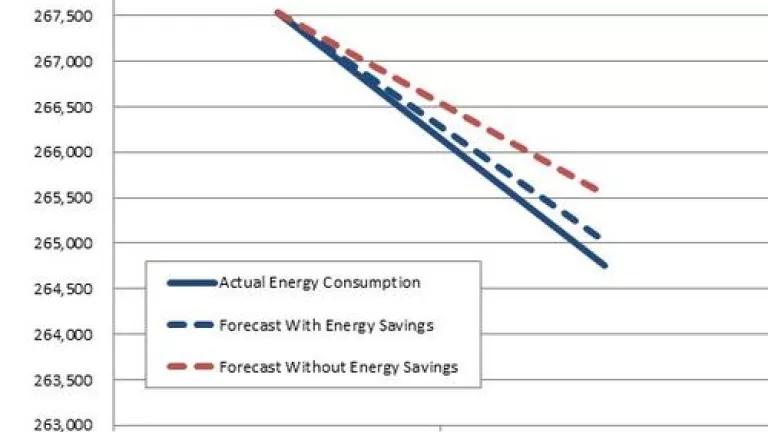

When the Energy Commission accounted for planned energy savings — and 2013 was the first year ever to have such a forecast — the forecast that included future energy savings was the best predictor of actual energy consumption. It was much better than the forecast that omitted those planned energy savings — and incomparably better than the historically implausible “high” forecast. Take a look for yourself, here are the official forecasts for 2013 compared to actual consumption in 2013, which was presented at yesterday’s meeting:

California Energy Commission 2013 Statewide Electricity Forecast

Compared to Actual Consumption

Source: California Energy Commission

Lesson learned: Counting the full amount of energy savings is a critical to getting the forecast right.

By including expected energy savings (from new utility efficiency programs, future building efficiency standards, and expected appliance efficiency standards), the commission came pretty close to getting it right. But they still overshot it. Given that forecasts will (inevitably) miss the mark, maybe the overshooting is just due to chance? In that case, looking at many forecasts over history, we should expect to see a balance of overshooting and undershooting. Plus, one year of data isn’t enough to know if the forecast is generally heading in the right direction — we need many years of data, because energy savings and other factors have a bigger impact over a longer period of time. So what do the forecasts look like over those many years?

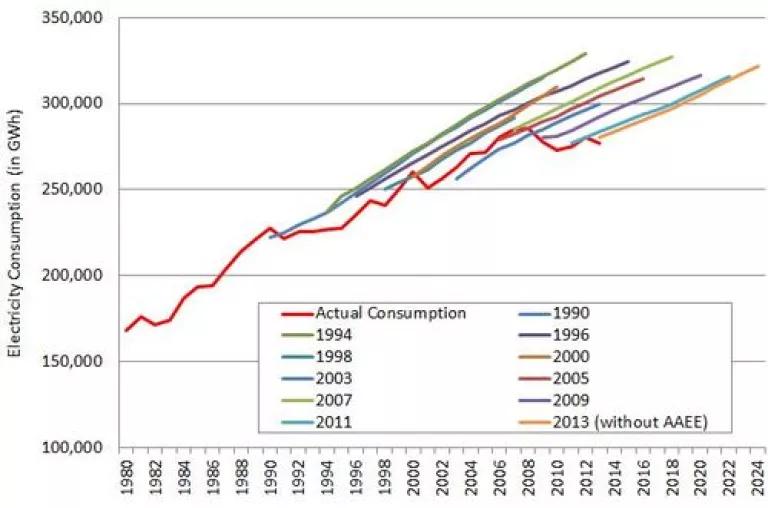

Every forecast since 1990 has overshot actual consumption in the long run. (Something I have testified to previously.) But not only are the end points over-estimating actual consumption, the overwhelming majority — we’re talking 90% — of yearly data points overshot it, too.

History of California Energy Commission Statewide Electricity Forecasts

Compared To Actual Consumption

Source: California Energy Commission

What does this mean for dirty power plants and the unhealthy pollution they leave in the air? Well, the California Public Utilities Commission allows the investor-owned utilities to build more power plants based on which version of the energy forecast the commission thinks is right. Depending on the forecast it chooses, California could build unnecessary power plants, wasting utility customers’ money. Or it could end up with too few — leading to reliability issues. In order to strike the right balance, the commission aims to use the most realistic energy forecast. After it gets the most realistic forecast, it then builds in plenty of reliability measures on top of the forecasted need (for the energy geeks reading this, that means authorizing adequate resources to meet planning and operating reserve margins).

But in the current process where the Public Utilities Commission is deciding whether to build new power plants, some people are claiming that we shouldn’t fully count on these projected energy savings in the forecast. Incredulous as it might seem, they are arguing that we should go back to the era of erroneous forecasts, back when we didn’t count on the planned energy savings. Not only that, they argue we should use an even higher (even more unrealistic) energy needs forecast than all those presented in the historical figure above (it’s called the “High Scenario”).

Now, the people making these arguments are the same people who make money on new fossil-fueled power plants, so their argument is not surprising. But it is critical for Californian’s pocketbooks and for their health (which suffers due to the dirty pollution coming out of fossil-fueled power plants) that the Commission does not decide to build more pollution-emitting power plants than it actually needs. And that means getting the forecast right.

While 2014 has been a good year of progress on energy forecasting due to the California Energy Commission’s first-ever forecast that includes future energy savings, let’s hope the Public Utilities Commission maintains this progress in 2015 by deciding to fully count on planned energy savings.