The UK Is Winning on Food Waste. Are We?

Now more than ever, as many people are trying to avoid unnecessary trips to the grocery store, food insecurity rates are growing by the day, and shortages of some foods loom, people are thinking about how to fully utilize all the food in their fridges and pantries.

Now more than ever, as many people are trying to avoid unnecessary trips to the grocery store, food insecurity rates are growing by the day, and shortages of some foods loom, people are thinking about how to fully utilize all the food in their fridges and pantries.

As indicated in the joint agency Winning on Reducing Food Waste Initiative, it’s critical to focus efforts on reducing the amount of food going to waste at the household level, because we have long known that households collectively are the biggest generators of food waste in the United States. If the US—and any city or state within it—wants to make meaningful reductions in the amount of food that is wasted, households are a critical piece of the puzzle.

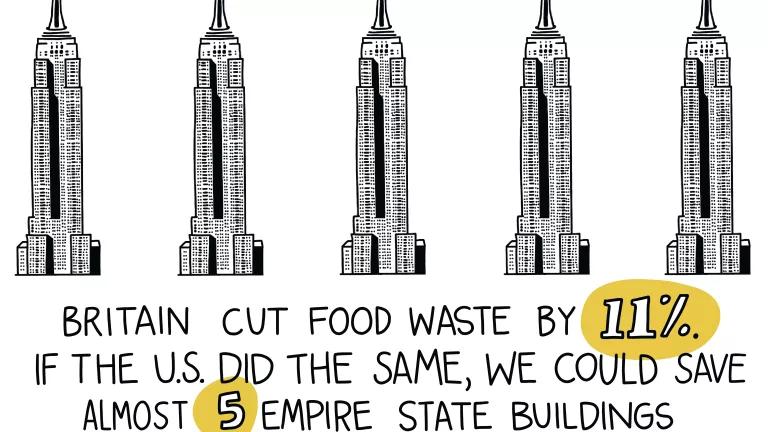

Britain cut household food waste per person by almost 11 percent in just three years. If the United States did the same, it would be enough to fill nearly 5 Empire State Buildings every year (having walked by the Empire State Building every day for 3 years, that’s a lot of food waste).1 But Americans are throwing out the same amount of food per capita as we have for the past 20 years.

How did Britain do it? Tackling household food waste made the big difference.

Good food is being thrown out, while many don’t have enough to eat. But when food is wasted, it’s not just about the food itself—wasting food also wastes all the resources that went into producing, storing, and transporting the food, like water, energy, and labor. In addition, food waste is a leading contributor to climate change.

A new study lays out how Britain cut household food waste. WRAP, the author of the study, cites three key reasons for the drop in UK household food waste generation:

1. Targeted public campaigns: Like wearing seat belts, getting everyone to change their behavior is a tricky challenge. To help consumers waste less food, Britain launched a targeted campaign: Love Food Hate Waste. Based on insights gained from research and surveys, the campaign promotes actions that could have the biggest impact by zeroing in on the food products wasted the most in Britain, and the populations that do the most wasting.

Every day in Britain, for example, people throw out 20 million slices of bread—mostly because it is stale. A new “Make Toast Not Waste” campaign encouraged consumers to freeze bread, then make toast directly from frozen slices.

2. Improved labeling: Confusion over food labels—stemming from multiple dates on the same package, inconsistent wording, and lack of education around the meanings—often causes consumers to throw out food prematurely. In the UK, roughly 20 percent of avoidable household food waste is due to label confusion. To confront this problem, WRAP worked with the British food industry to issue new labeling guidance in 2017, and updated it in 2019. The guidance includes specifications that date labels must be on the front of the package, “Use By” should appear only on food items that pose a potential food safety risk, and “Best Before” should be used in most other cases only to indicate peak quality. Adoption of these best practices is tracked through a regular survey of retailers. Survey results and additional research are used to continuously update the guidance with relevant labeling and packing instructions, such as removing labeling completely from most fresh produce.

3. Increased curbside organics collection: In 2018, the British government rolled out a weekly curbside organics collection for its residents in Wales, Northern Ireland and Scotland, soon to be universal in England. Even in the most food waste-conscious households, there will always be some food scraps that cannot be eaten, including inedible parts of food that are put to their best use if composted or anaerobically digested to transform organic waste into useful soil amendments. Making it easy for residents to recycle food scraps will help keep household food waste out of the landfill.

The United States, however, isn’t seeing this progress. In December 2019, the Environmental Protection Agency released its latest facts on municipal solid waste generation (with data through 2017). The data show that per capita food waste generation between 2015 and 2017 remained the same—4.76 pounds per person per week. If we want this number to go down, we must learn from Britain and dramatically increase our focus on residential food waste. Now is the time to get this right.

Here’s how the United States can catch up:

1. Target behavior change: NRDC’s campaign, Save the Food, spreads awareness about food waste, offering the public helpful, actionable tools and information. While this campaign has boosted awareness greatly, there is still need for individuals (as well as other players in the food system) to take ownership of the changes that will reduce their waste. We know that this can be tricky—the US has a huge population and diverse communities that may respond best to different messages. Residential food waste is usually the product of good intentions—wanting to provide healthy options and a variety of food, stocking enough food for emergencies, etc.—we don’t want to change the motivations, just the behaviors that lead to wasting food. And we don’t yet know enough about what interventions work—but it’s time to try more.

We need more programs to help guide Americans to prevent good food from going to waste. Efforts are underway across the US to figure this out—NRDC and the City of Denver are integrating wasted food prevention messages into outreach materials to Denver residents, and the National Academy of Sciences is undertaking research to deliver recommendations on tactics that could effectively get Americans to reduce food waste, among many others.

Drawing on lessons from the UK, we could also focus on the most wasted foods through a campaign. With coffee being 1 of the 6 most commonly wasted edible foods in NRDC’s study of households in three US cities, how about a campaign called “Make good coffee, not bitter waste”?

Testing the strategies and measuring results will require broad support and action from many.

2. Standardize date labels and educate consumers: In the United States, more than 80 percent of consumers report that they discard food prematurely due to confusion over date labels.

The problem is that date labels are not federally regulated, with the lone exception of infant formula. For the most part, dates on food labels indicate the manufacturer’s best guess as to when the product will be at peak quality—it does not indicate anything related to food safety. That means it’s up to states, cities and counties to come up with their own regulations on which food items must have date labels. Currently, 41 states plus the District of Columbia require date labels on at least some food items, though the type of item and rules differ. It’s complicated.

But there’s hope. In 2019, The Food Date Labeling Act was introduced, and if successful, would make date labels clear and consistent across the country. The act would limit date labels to “Best if Used By” to describe product quality, and “Use By” for the relatively small number of highly perishable products or those that may present food safety concerns. This standardized labeling approach would allow consumers to easily distinguish whether the date indicates quality or safety. Equally important, if the legislation passes, will be ensuring that consumers understand the new labeling system.

A coalition of partners, including NRDC, have been advocating for date label reform for years. In 2020, when we’ve already seen child food insecurity rates quadruple as a result of the coronavirus pandemic, we need to make sure no food is wasted due to confusion about its safety.

3. Get people to compost: Only 6.3 percent of the food waste generated in 2017 was composted. Most ended up in a landfill, where food and other organics create methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. During the COVID-19 pandemic, many cities have cut back on recycling and composting services to households. If we want to reduce the amount of food going to disposal, we need to ensure that cities restore and expand their organics recycling collection and processing services.

In the UK, producers of packaging are required to follow producer responsibility regulations, which ensure that they focus on reducing and recycling the materials they introduce into commerce that enter the municipal waste stream. In order to help relieve the burden on municipalities and taxpayers for financing waste systems, we need to bring producers into the loop (e.g. through producer responsibility laws) to share financial responsibility for recycling the products and packaging they introduce into commerce and to participate in reducing the amount and complexity of materials in our waste stream.

In the face of these challenges, support for small-scale, community composting, like this effort in Baltimore, must continue to grow. Through NRDC’s Food Matters project, we are working with cities around the US to boost these efforts.

Programs in the US to address food waste have been monumental, but we still have a long way to go. If we want to cut food waste going to landfills and incinerators in half by 2030 in the US, we must ramp up our attention to households. The UK has shown the world it’s possible. Let’s follow suit.

[1] Total US food waste generation in 2017 was 40,670,000 tons. The volume of the Empire State Building is 37 million cubic feet. Assuming 33.5lbs of food waste per cubic foot (range is 22-45lbs, for this purpose, we used the midpoint), a 7% reduction in total food waste generation in the US would fill the empire state building 4.6 times.