Tribal Traffic Fatalities Demand Federal Investment

Roughly 535 Indigenous people die every year from vehicle crashes, at a rate significantly higher than other racial/ethnic groups in the United States.

Photo by yesy belajar memotrek on Flickr

This is the first of a two-part blog post series on Tribal road safety and infrastructure solutions written by Tala Parker, 2022 Summer Schneider Fellow for Transportation at NRDC. View the second article here.

A man sets out from his house to the grocery store on foot. He carefully walks along the roadway as cars woosh by. It’s a journey that may end his life. A young family forbids their children from leaving the house to play outside for fear that they may be struck by a vehicle. A driver entering the Reservation becomes hyper-vigilant for pedestrians, fearing that she may not see them before it’s too late as they try to cross the intersection with no stop lights or crosswalks.

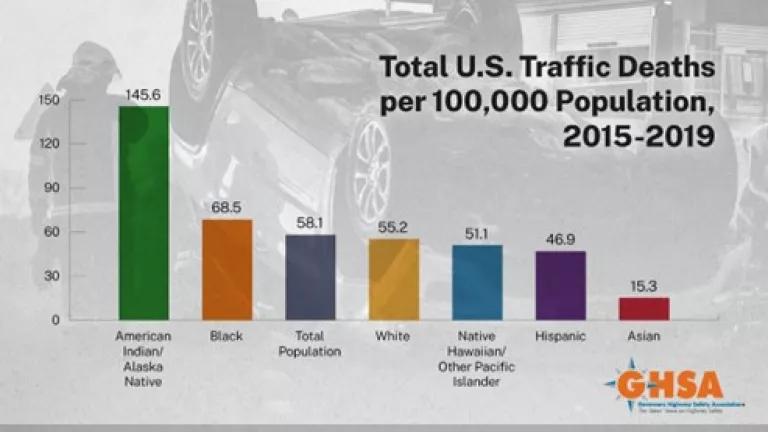

This is reality for many Indigenous people in the United States, who face the highest traffic fatality rates of any racial or ethnic group in the United States. Whether driving, walking, or biking, Indigenous people are the most at-risk population for vehicle-related injuries and deaths—and have been for some time. A 2004 report stated that the leading cause of death for Indigenous people between 10 and 64 years was a motor vehicle crash; the fourth leading cause of death was being hit by a car as a pedestrian. A 2018 study, citing federal data, reported that approximately 535 Indigenous people die every year from vehicle-related crashes. Smart Growth America’s annual “Dangerous by Design” report shows the continued rise of pedestrian-related fatalities during the pandemic due to more drivers speeding on less-trafficked roads, perpetuating existing disparities in traffic risks for Indigenous populations.

I want to pause here for a moment, because it can be hard to truly understand what it looks like for 535 people to die, especially if you are not directly impacted by one of those deaths. I invite you to sit with that number and allow yourself to feel outraged, horrified, and sad.

Analysis of Traffic Fatalities by Race and Ethnicity, Governors Highway Safety Association, 2021

Why are Indigenous people disproportionately killed by vehicles? The short answer is that transportation infrastructure is unsafe in places where they live and work. The first problem is the state of roadways on Tribal lands, which are often unpaved and undermine safety for all road users. In fact, 75 percent of Tribal roads are made of gravel or dirt. These roads can create unsteady driving conditions, especially for larger vehicles like school buses. Tribal Nations across the United States struggle to get their children from rural homes to schools in a timely and safe way, a problem exacerbated by these poor road conditions, which are in turn rooted in a history of disinvestment.

A second major contributor to elevated traffic fatality risks for Indigenous people is the lack of pedestrian infrastructure on reservation and Tribal area roads. It is common for these roads to lack sidewalks—in particular roads made of gravel or earth. People living on Reservations often “...avoid sending their children out to walk or bicycle because there is no safe shoulder or sidewalk for them to do that,” the authors of the 2018 study found. Without the requisite public sector investment in safe sidewalks, people are often forced to walk on narrow shoulders in close proximity to cars, where people are hard to see, especially at night.

Indigenous people are also less likely to own a vehicle than the average rural resident, in large part due to high poverty rates. One study found that “about 9% of households in Tribal areas do not have a vehicle, which is similar to the U.S. average but more than twice as high as the rate in other rural areas across the country.” Without cars, people more often depend on public transportation, biking, or walking. Yet many Tribes do not have adequate public transportation such as widespread bus service, so people have to walk to get to vital services such as grocery stores and shops as well as workplaces and hospitals. Because more people must walk to their destinations and do not have safe pedestrian infrastructure to use to get there, they are at higher risk for vehicle crashes.

Inadequate public transportation options paired with the lack of reliable household vehicle access can also exacerbate other harms, for example by serving as a motivator for higher-risk transportation choices like hitchhiking. The 2006 Highway of Tears Symposium Recommendations Report identified the combination of poverty and a lack of public transportation service as key contributing factors to a string of missing and murdered Indigenous women in British Columbia, Canada, for example.

Roughly 535 Indigenous people die every year from vehicle crashes—which is 535 too many. Pedestrian safety has become an increasingly important concern for Tribal residents and Tribal governments, and this pressing issue has even been acknowledged and emphasized by Transportation Secretary Pete Buttigieg: “Native Americans are more likely than any other group in our country to lose their lives in roadway crashes”.

The bipartisan infrastructure law has specifically allocated resources for Tribal infrastructure issues, which have the potential to alleviate transportation and other critical Tribal infrastructure challenges, including through investments in broadband infrastructure to reduce the digital divide. As we work to ensure that these historic investments align with national climate goals, we also need to ensure that these investments address historic harms in our most-impacted communities. In the next installment of this two-part blog series, we will examine the scale of the infrastructure law’s investment in Tribal transportation systems to gauge whether our government is doing enough to address this problem.