These Montanans Don’t Want an Industrial Slaughterhouse in Their Backyard

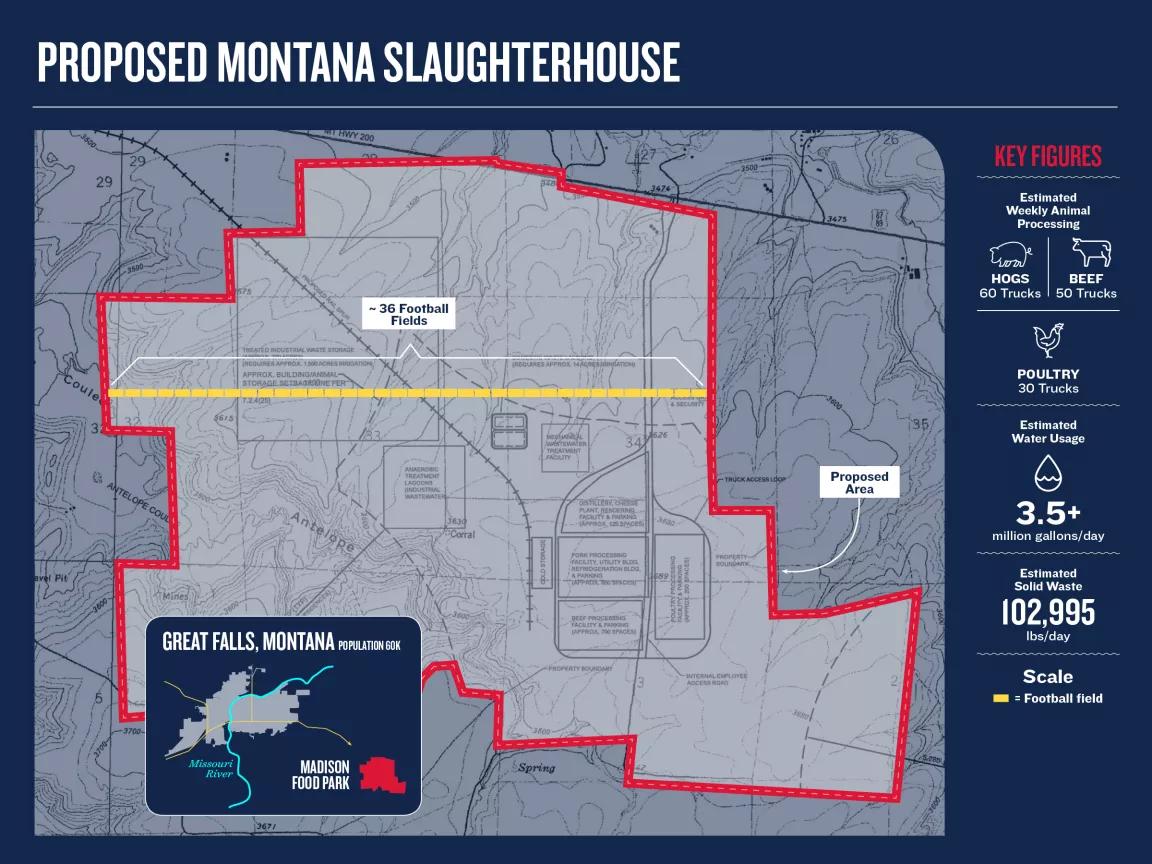

In the small city of Great Falls, residents push back against a Big Ag plant that would consume 3.5 million gallons of water—and produce 102,995 pounds of waste—per day.

Stacy Hermiller was worried about her family's health and her property value when she found out a meat-slaughtering facility was being planned near her home east of Great Falls.

Stacy Hermiller has deep roots in Big Sky Country. A fifth-generation Montana resident whose family has lived there since 1901, she fits the state’s outdoorsy profile, actively enjoying fly-fishing, hiking, backpacking, and all manner of wilderness pursuits.

In 2008, when Hermiller bought a 20-acre piece of property about eight miles southeast of Great Falls, she had a picture-perfect idea of the rustic life she’d build there. That was before she received the certified letter in the mail.

The letter described a proposed slaughterhouse in the works for the property next door. Hermiller’s neighbor across the highway didn’t receive such a letter; the county only notified those whose property shared a fence line with the project.

Curious, Hermiller looked up the plant’s plans, detailed on the county’s website. There, she discovered that the Canadian company Friesen Foods wanted to construct Madison Food Park—which would become the largest meat-processing plant in Montana—in her community, known mostly for its small-scale agricultural businesses and Air Force base and as a gateway to several state and national parks. Friesen would transform 3,000 acres (a tract about six times the size of Disneyland) into a “multi-species food-processing plant for cattle, pigs, and chickens and the further processing facilities for beef, pork, and poultry.”

Not only would the sheer size of the facility overwhelm Great Falls, a city of almost 60,000 residents, but it would also contribute a vast amount of pollution. For starters, it would produce more than 300 acres of treated industrial waste, to be disposed of in domestic waste lagoons. Across 260 days a year, its operators would process thousands of animals 24 hours a day in three eight-hour shifts, according to the project’s application. Every day, dozens of trucks would transport animals to the facility and carry meat away, along the two-lane U.S. Highway 89. The parking lot would accommodate 1,900 vehicles.

“I was horrified. It was literally in my backyard,” Hermiller says. The region was zoned for agriculture and didn’t offer an adequate parcel of industrially zoned land. So the county planning board had voted to change allowable uses for the land under a special-use permit law. Hermiller notes that Cascade County advised its commissioners to vote the changes through—and that they ended up approving them unanimously. “The meeting was public, but it was not well advertised, so no members of the public were present to debate or offer comment,” she says. As a result, when they first saw the plans, Hermiller and her neighbor were “dumbfounded and helpless. We just couldn’t believe what we were looking at.”

A physician’s assistant at an orthopedic surgeon’s office, Hermiller hadn’t been active in local politics. But spurred by concerns about how an industrial slaughterhouse could impact the local environment and quality of life in Great Falls, she banded together with neighbors to learn more about the proposed food company and get organized, forming Great Falls Area Concerned Citizens.

“Citizens are right to be wary,” says NRDC’s Valerie Baron, an attorney focusing on sustainable agriculture and antibiotics as well as health and food. Though Friesen touted the promise of new local jobs, she notes, “Many slaughterhouse jobs are among the most dangerous. The risk of workplace injury is high, but there is also a significant risk from pathogens.” Studies show that workers in slaughterhouses and factory farms are at risk from potentially deadly antibiotic-resistant bacteria, and Baron points out that workers can bring these bacteria home. Moreover, slaughterhouses can invite other environmental hazards, including an influx of heavy truck traffic, and can encourage other dangerous mega food-production facilities to move in.

Community meetings started with 60 or so residents in the fall of 2017. By the following spring, the Great Falls Area Concerned Citizens’ presentations, with guest speakers from the Socially Responsible Agriculture Project and elsewhere, were attracting up to 450 attendees, according to Hermiller.

Waters at Risk

Residents are drawn to Great Falls for the area’s natural beauty. What’s more, homes are cheap and the air quality is good. The city even made a Forbes “25 Best Places to Retire” list, in 2015.

Water in this part of north-central Montana is a defining feature. Residents can hike a trail that winds for 58 miles along the state’s longest river, the Missouri, which flows past Great Falls. Nearby are five waterfalls and one of the largest freshwater springs in the United States. Giant Springs (first recorded by Lewis and Clark in 1805) produces 156 million gallons of water per day, originating in an opening in the Madison aquifer in the nearby Little Belt Mountains. A wetland-rich wildlife refuge sits just north of Great Falls, and the Roe River, often called the “shortest river in the world,” flows between Giant Springs and the Missouri.

“The Missouri River is the heart of the Great Falls community and the surrounding area,” says Zack Strong, an NRDC attorney and wildlife advocate who grew up there. “We used to fish, swim, wade, paddle, and splash around with the dogs in the river throughout the year. Building the proposed slaughterhouse would put the Missouri at risk and jeopardize the local economy, wildlife, recreation, and residents’ quality of life. Allowing the river to become polluted would be devastating.”

Madison Food Park—so named for the aquifer it would pull from—would also rely heavily on the region’s water, consuming a total of 3.5 million gallons of water per day via three or four deep-water wells. Great Falls residents know this alone would spark conflict: Throughout Montana, agriculture interests and residents engage in “water wars” as they battle over access, notes Guy Alsentzer, executive director of the nonprofit Upper Missouri Waterkeeper. “There’s a saying in Montana: ‘Whiskey’s for drinking, and water’s for fighting,’ ” he says. Agriculture is also the single-largest source of nutrient and sediment pollution entering the waters of southwest and west-central Montana, according to the group.

In the original proposal, Friesen Foods estimated that 102,995 pounds of animal waste would be generated by the operation per day. It also anticipated that “99.6% of the solid and liquid waste produced” would be either recycled using anaerobic digestion technology; repurposed into agricultural commodities; or rendered into pet food, fertilizer, or other protein meal. The company, coincidentally, had previously focused on producing animal feed.

Alsentzer notes that despite the promises, the proposal was disturbingly lacking in specifics about how any of that recycling, repurposing, or rendering would be accomplished. “The entire facility’s waste management is going to be a big threat to groundwater,” he says. The proposed site is at the headwaters of Antelope Creek, and the nearby Sand Coulee Creek flows into the Missouri River.

In Montana, surface waters (including runoff or spills) are connected to the groundwater through a porous soil, and as anywhere, the groundwater interacts closely with local waterways. “You put any pollution into local groundwater and it probably affects nearby streams and rivers,” says Alsentzer.

Most large-scale agricultural facilities take lagoon waste—a “nasty soup of strained blood and guts,” as Alsentzer describes it—and spray it onto the property’s soil and grass as fertilizer (and simply as a way to get rid of it). “It can have minimal impact for small-scale slaughterhouses,” Alsentzer says, but not at the industrial level. “Whether the waste is stored as solids or liquids in open lagoons, the scope of likely water pollution is boggling.”

The waste can contain some pretty bad stuff: for starters, nitrogen and phosphorus, which, should they leach into waterways, disrupt the food chain by creating oxygen-sucking algae blooms that kill off aquatic populations. There’s also E. coli, antibiotics, and antivirals. “There’s an overall cumulative threat,” Alsentzer says, especially given that the Missouri River is less than 10 miles, as the crow flies, from the proposed slaughterhouse. “If there’s a percolation into the groundwater from the lagoons, how will they even monitor for it, over dozens and dozens of acres?”

The record speaks for itself. Three-quarters of large U.S. meat-processing plants that discharge wastewater directly into streams and rivers violated their pollution-control permits in the past two years by discharging bacteria, pathogens, nutrients, and other materials, according to a report from the Environmental Integrity Project (EIP), based on U.S. Environmental Protection Agency records.

Wait and Watch

In May 2018, without any official statement regarding its reasoning, Madison Food Park announced it would amend its application and requested more time to make the changes. “The widespread, vocal, consistent public opposition certainly played some role,” Alsentzer says.

There’s no deadline, so a new application could be submitted at any time. And Hermiller, who sold her property not long ago, suspects that Friesen will regroup and come back “bigger, stronger, and more effective.” But she doesn’t expect the community to back down from its fight against the Big Ag plant. “We don’t want to be complacent.”

“We have more cows than people in Montana,” Hermiller observes wryly. “I’m not against the slaughterhouse industry; I want responsible beef slaughterhouses. This is not responsible ranching, and it’s not what Montana was built on. We’re the ‘last best place on earth,’ ” she adds, stating Montana’s unofficial motto. “Let’s keep it that way.”

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

In Planning for Climate Change, Native Americans Draw on the Past

Biodiversity 101

Blackfeet Nation Is Taking Back the Food System