A new study released today shows that taking steps to significantly reduce carbon emissions as part of planning our future electric generation and transmission mix would cost about the same as ignoring the climate threat, while avoiding a whopping 33 billion tons of CO2 pollution along the way. Synapse Energy Economics has conducted an analysis showing that the price of the future generation and transmission infrastructure mix necessary to slash carbon pollution to 80 percent below “business-as-usual” levels by the year 2030 - through more energy efficiency and transmission to move renewable power sources like solar and wind - would be essentially the same as the costs of a mix designed without regard for carbon controls.

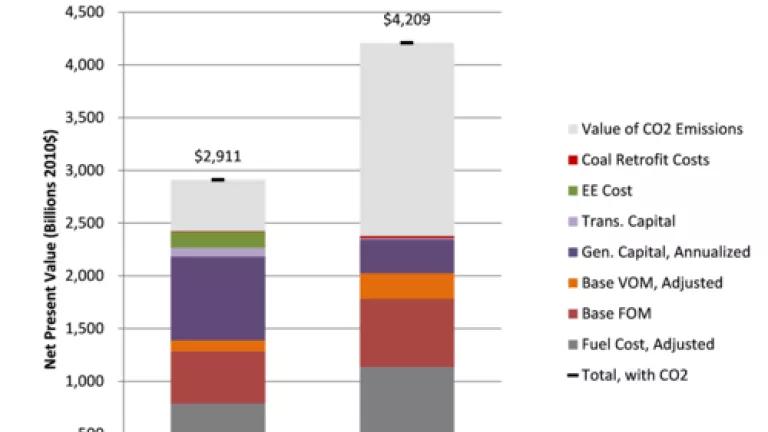

To be clear, improving our country’s power systems under either a so-called “business as usual” or “low-carbon” future, as we call them, will cost a lot – approximately $2.4 trillion. Of the two futures, however, only the low carbon future will avoid billions of tons of carbon pollution from power plants,- the biggest carbon polluters in the country.

And it gets better. If you actually account for the costs of carbon pollution in the modeling, the ‘low carbon future’ ends up more than $1 trillion cheaper than the business-as-usual future – quite a bargain.

With hefty cost and pollution savings like that it’s not so far-fetched for transmission planners to design grid improvements that will support the renewable energy and other clean resources necessary to fight climate change.

Synapse conducted its analysis on behalf of 27 public interest environmental groups involvedin a transmission planning effort known as the Eastern Interconnection Planning Collaborative, or “EIPC.”

What is EIPC and why does it matter?

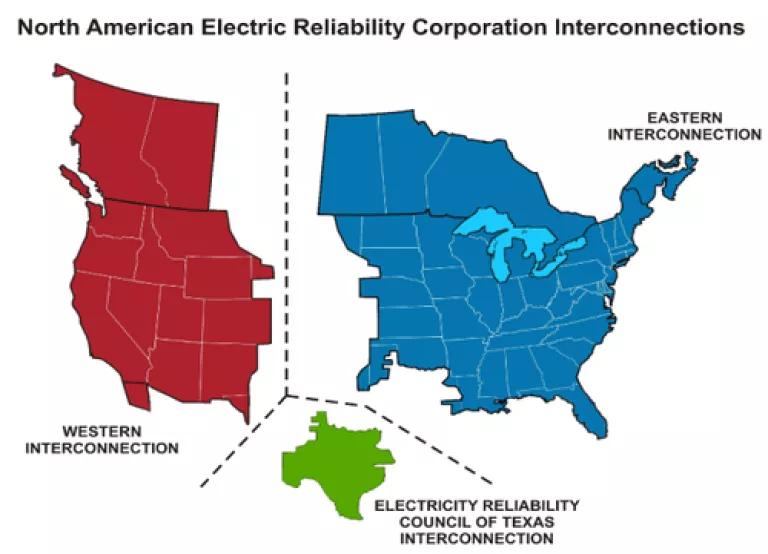

The EIPC was an almost three-year effort funded by the U.S. Department of Energy to study more efficient ways to plan for future transmission system needs throughout the Eastern Interconnection. The Eastern Interconnection is the transmission grid that electrically connects the 39 states, District of Columbia and 8 Canadian provinces on the Eastern side of North America.

Very simply put (or perhaps as simply as this esoteric process can be put), the EIPC process brought together a broad array of stakeholders – utilities, power generators, consumer advocates, environmental organizations, state regulators and others – from across the Eastern Interconnection. These stakeholders hired power system modeling experts to co

mbine the transmission plans from all the utilities’ across the Interconnection into one great big transmission system plan. (A transmission plan is a transmission-owning utility or region’s 10-20 year plan to upgrade existing transmission infrastructure and build new lines necessary to support expected demand in its area while maintaining reliability and, hopefully, keeping costs low.)

Once the plans were combined, the experts modeled over 80 different sets of ”policy futures” (things like federal clean energy policies or business-as-usual with sensitivities like high or low gas prices, and high economic growth or low economic growth) to determine what possible generation resource mixes would exist under different futures. Finally, after sometimes intense debate, the stakeholders chose for further modeling three of the energy futures, to determine the necessary transmission system build-out and related costs for each one. Although the EIPC effort produced a wealth of important and useful data, the EIPC Phase II report itself recognized limitations in the cost modeling aspects of the EIPC work. Instead of modeling the total costs of each of the three futures over time, EIPC looked only at a “snapshot” of each future’s O&M costs for one year, 2030, as well as the “overnight” capital costs of the futures (just last week, the New York Times pointed to EIPC’s cost modeling results).

The Synapse Findings

After the EIPC study process concluded, the environmental groups asked Synapse to take what we viewed as the next logical step – to use the inputs and results of the EIPC modeling to discover the total costs of the three energy futures through 2040 so that we could compare them in an “apples to apples” fashion (for you econ folks, a “present value revenue requirement” analysis). Although the Synapse analysis modeled all three futures, the key findings from our perspective involve the comparison of the low carbon and business-as-usual futures.

Synapse’s results are important and encouraging. The study means that, at least as applied across the eastern two-thirds of the United States, if we plan the transmission grid to combat climate change it will not cost more, overall, than just ignoring the climate threat. Instead, if we account for the price of carbon pollution, it will cost significantly less.

And that is an encouraging conclusion for the utilities, their customers, and our planet.