Since 2013, we have seen significant changes in China’s coal consumption trends, with coal beginning to peak and plateau in 2013 and fall by 2.9% in 2014 and 3.7% in 2015 in physical tons.

The latest energy consumption data for 2016 released by the National Bureau of Statistics at the end of February show that while China’s total energy consumption increased by 1.4% in 2016, coal’s share of total energy consumption actually fell from 64.0% in 2015 to 62.0% in 2016. Measured in physical tons, coal consumption fell by 4.7%, from about 3.97 billion tons to 3.78 billion tons, a drop of about 190 million tons. Measured in terms of energy content, which is what matters for CO2 emissions, China’s coal consumption fell by about 1.3%.

As a result, China’s energy and cement-related CO2 emissions in 2016 were basically flat, continuing a leveling off of its CO2 emissions since 2014. This plateauing of coal consumption provides an important opportunity for China and the world to peak global CO2 emissions at an earlier and lower level. The graph below, from analysis by Dr Jan Ivar Korsbakken and Dr Glen Peters at CICERO, shows the plateauing of China’s CO2 emissions, due to peaking and now falling coal consumption. The CICERO researchers estimate that based on the recent NBS data, CO2 emissions in China increased by about 0.5% in 2016.

The last few years mark an extremely significant change in China’s energy structure, economy, and carbon emissions. These changes were caused both by China’s changing economy—slower economic growth under China’s “new economic normal”—and by China’s proactive policies in the last decade to control coal consumption and grow wind, solar, and other renewable and low-carbon energy sources.

China’s First Ever Mandatory Target for the Share of Coal in Total Energy Consumption

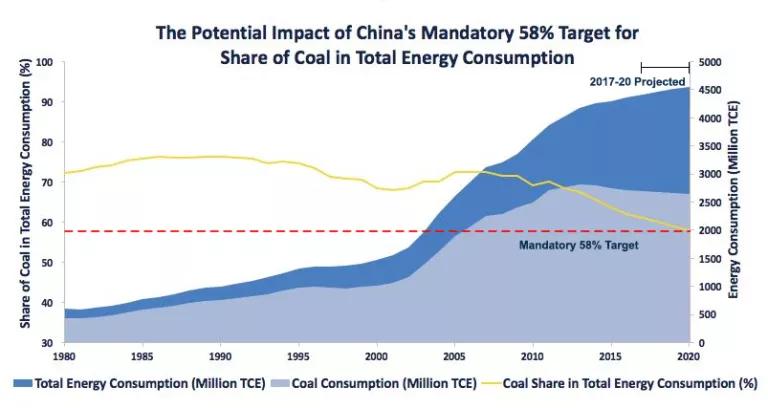

China has also recently strengthened its efforts to reduce the share of coal in its energy structure. The Thirteenth Five Year Energy Development Plan, issued by the National Development Reform Commission (NDRC) and the National Energy Agency (NEA) in December (Chinese here), establishes, for the first time, a mandatory target for decreasing the share of coal in total energy consumption. The plan aims to have China’s coal consumption account for no more than 58 percent of national energy consumption by 2020, a 6 percentage point reduction from the 64% share in 2015. As shown in the graph below, coal consumption from 1980 to 2013 has ranged from 67.4% to 76.2%, so reducing the share to 58% would mark a significant shift in China’s energy structure.

This 58 percent target is one of only five targets in the energy plan that are deemed “mandatory”, with the other four mandatory targets (all for 2020) being to:

- reduce energy intensity by 15%,

- reduce carbon intensity by 18%,

- increase the share of non-fossil energy to 15%, and

- reduce the average coal consumed supplying a kilowatt hour of electricity for coal-fired power plants to less than 310 grams of standard coal per kilowatt hour.

The decision to make the 58% target a mandatory one indicates that policymakers view this as an important “must achieve” target, and will be strengthening policies and measures to achieve the target.

As noted above, the share of coal in total energy consumption fell to 62% last year, the lowest it has ever been, and the NEA has indicated in its recent 2017 work plan (Chinese here) that it will aim to reduce the share to 60% this year. So it’s quite possible that China will over-achieve this target by 2020, as it has with energy intensity and carbon intensity targets in the past.

While China also set a total energy consumption cap target of 5.0 billion tons of coal equivalent for 2020, it is likely that the actual level will be lower, due to slowing demand growth. In that case, the mandatory 58% target for coal’s share in total energy consumption would mean that coal consumption as an absolute amount also continues to fall through 2020. For example, if total energy consumption reached 4.55 billion tons of coal equivalent (tce) by 2020, a 58% share for coal would translate into about 3.70 billion physical tons of coal.

Achieving the target to reduce the share of coal in total energy consumption to 58% or below will require contributions from a range of provinces and cities, especially those in key air pollution regions which already have the responsibility to reduce their absolute coal consumption, as well as in key coal-consuming sectors like the power sector (more on this below), iron and steel, and cement, as set forth in the China Coal Cap project’s recommendations for the 13th Five Year Plan. The China coal project recommendations found that reducing coal’s share to 55% and decreasing coal consumption to 3.5 billion tons by 2020 would be possible with more aggressive efficiency and coal replacement policies, and would bring significant health, social, and environmental benefits.

Reducing Coal Consumption in the Power Sector, Through Greater Integration of Renewables and Low Carbon Generation

China’s power sector is currently in a key transition phase, from a system in which coal power plays the dominant role to one in which it must increasingly give way to play a more balanced role with growing wind, solar and other low carbon generation sources. Coal power plants consumed 1.79 billion physical tons of coal in 2015, 45% of the total 3.97 billion tons of coal consumed that year.

As power demand growth slows under the new normal and the share of renewables and low carbon generation continues to grow, coal power plants are running for fewer and fewer hours and the risk of coal power plants becoming stranded assets becomes increasingly high.

In 2016, based on the latest figures from the China Electricity Council (see summary table at the end of this blog), China generated a total of 5,990 Terawatt hours (TWh), a 5.2% increase from 2015. Coal power generation represented the largest share, at 3,906 TWh, or 65.2% of total generation, a 1.3% year-on-year increase. Even with this increase, however, the average utilization of thermal power plants (mainly coal, with a small amount of gas-fired power) fell 199 hours, from 4,364 in 2015 to 4,165 in 2016, only a 47.5% utilization rate.

The next largest electricity source, hydropower, increased 6.2% year-on-year to 1,181 TWh, a 19.7% share of total generation; wind power grew 30.1% to 241 TWh (4.02% of total generation); nuclear power grew 24.4% to 213 TWh (3.56% of total generation); natural gas-fired power grew 12.7% to 188 TWh (3.14% of total generation); and solar power grew 72% to 66.2 TWh (1.11% of total generation).

Because of the new generation from hydro, wind, solar, natural gas, and nuclear power, the share of coal-fired power in total generation fell from 67.7% in 2015 to 65.2% in 2016. Moreover, of the 296 TWh of additional generation in 2016, 51.9 TWh, or 17.54%, was from coal power plants; even with high curtailment rates (discussed further below), low carbon generation sources made significant new contributions. Hydro accounted 23% of added power generation in 2016, while wind and solar accounted for 28%.

Because of the rapidly changing structure of electricity generation, there is a need to limit the growth of coal power plants to a more reasonable level and develop policies to improve integration and reduce curtailment of renewables.

The Thirteenth Five Year Energy Development Plan sets a target for coal-fired power capacity to increase from about 900 gigawatts (GW) in 2015 to up to 1100 GW in 2020. In January, China suspended 120 GW of coal power plants that were either planned or currently under construction, although another 140 GW of capacity is still under construction. The China Coal Cap Project recommends capping coal fired-power capacity at 990 GW by 2020 in order to avoid stranded assets and set the power sector on a greener path.

Addressing Renewable Energy Curtailment with Distributed Generation, Improved Transmission and Dispatch

One of the largest challenges for greening the power sector is the high rates of curtailment for wind and solar energy. In 2016, 17% of China’s wind power was curtailed (link in Chinese). This 49.7 TWh of wasted wind energy would have been enough to power the annual residential electricity use of almost ninety million Chinese residents. This is a record level of wind curtailment, up from 15% in 2015. Wind curtailment in the provinces with the most severe curtailment actually worsened last year – in Gansu province, wind curtailment increased from 39% in 2015 to 43% in 2016. In China’s western provinces of Gansu and Xinjiang, solar curtailment was also severe, reaching 39% and 52%, respectively, in the first months of 2016.

China's Thirteenth Five Year Power Sector Development Plan (Chinese here) has set a goal to bring renewable energy curtailment down to 5 percent by 2020. To achieve this goal, China will:

- Increase distributed renewable energy generation, and develop large-scale renewables closer to demand centers. The Thirteenth Five Year Energy Development Plan calls for 56% of new solar and 58% of new wind installation to be in eastern and central China.

- Focus on renewable energy utilization growth, not just capacity growth. The Thirteenth Five Year Energy Development Plan calls for a tripling in the amount of solar electricity used, setting high wind utilization targets as well.

- Allow for market forces to help optimize the grid system. Long-term administrative power agreements that cover the capital costs of coal-fired power plants have propped up uneconomic capacity and have allowed coal power to be dispatched before renewable resources. China will be initiating its national spot market in 2018, but the details of the market are still unclear. China has also announced that it will be initiating a green electricity certificate scheme, similar to the REC systems used in the US. This will provide additional revenue to wind and solar generation, especially as China reduces feed-in tariff subsidies.

- Plan for more transmission infrastructure investments alongside renewable energy investments (as highlighted in a Paulson Institute animation illustrating the promise of connecting the abundant wind resources of Hebei province to the increasing electricity demand in Beijing, spurred in part by the growing use of electric vehicles).

China continued to reduce its coal consumption in 2016, and its new mandatory target to reduce coal to 58% of total energy consumption by 2020 sets the stage for a fundamental transformation in its energy structure in the next few years. While many challenges remain, ongoing efforts to green the power sector, by limiting the role of coal power plants and boosting utilization of renewables, will be a key part of the solution to reducing emissions and decarbonizing the economy.

This post was co-authored with Princeton-in-Asia Fellow Noah Lerner.