Lithium Mining Must Not Dry Up the Atacama Desert

Our report offers eight recommendations for communities, governments, and the private sector throughout the lithium-ion battery supply chain to avoid further damage to this unique area and the people who live there.

"Bridge With No Water"

This blog post was co-authored by James J. A. Blair.

The world’s top climate scientists have agreed: humans are unequivocally causing global warming, and as a result, millions of people around the world are suffering. We must reduce our greenhouse gas emissions drastically – and soon – if we are to avoid the worst impacts of climate change. But global climate action should not sacrifice local ecosystems and communities that have lived in and shaped the landscapes containing critical materials for the energy transition.

Experts have also noted that many efforts to adapt to changing climate could actually make conditions worse for people and the planet. One example of this, called “maladaptation,” is mining of the critical minerals necessary for clean energy solutions like storage and electrified transportation. Indeed, these technologies have become central to energy transition policies to phase out fossil fuels, reduce air pollution, and mitigate greenhouse gas emissions. However, they rely on lithium-ion batteries, and their growing demand has led to a boom in destructive mining for critical materials, such as copper, nickel, graphite, manganese, cobalt, and of course lithium.

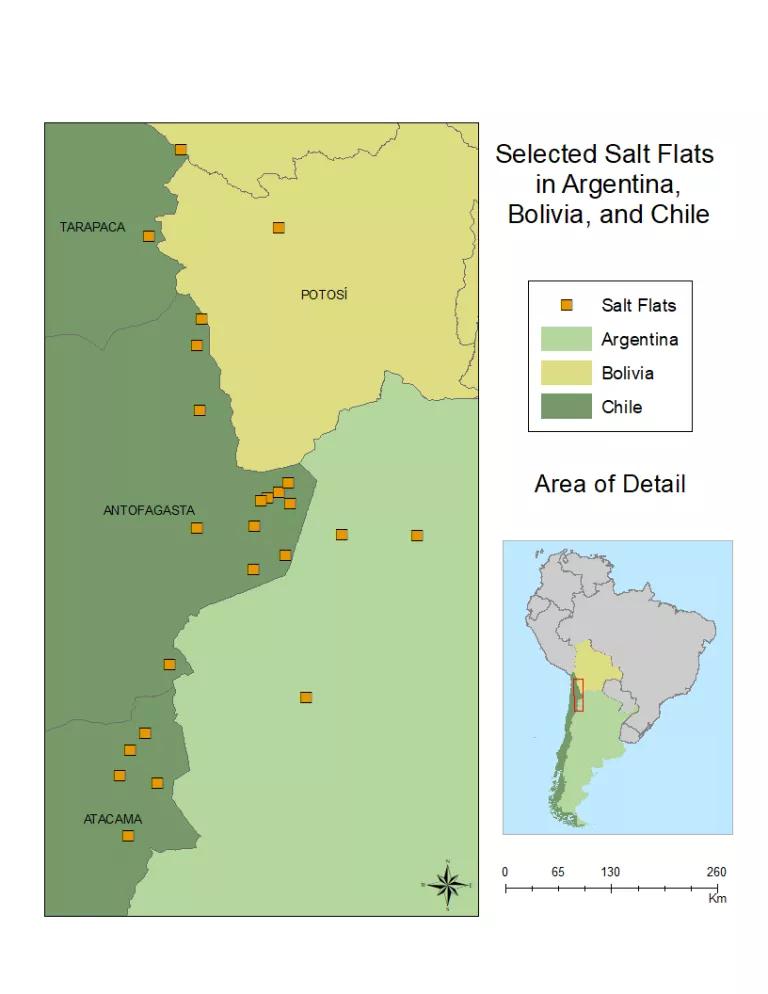

Our new report, Exhausted: How We Can Stop Lithium Mining from Depleting Water Resources, Draining Wetlands, and Harming Communities in South America, shines a light on the way lithium mining is worsening water scarcity among communities in the high, arid region that crosses the borders of Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile.

Selected Salt Flats in Argentina, Bolivia, and Chile

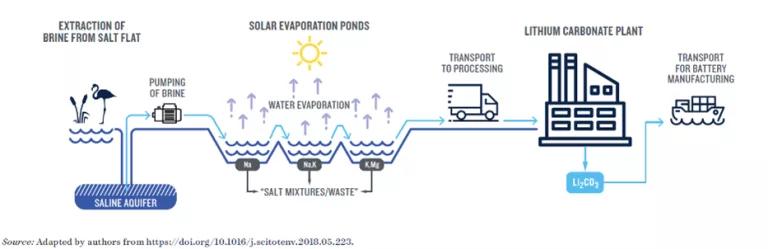

This region – the Puna de Atacama – has abundant salt flats (salares). Lithium is found in the brines that lie beneath those salt flats and is extracted using the evaporation method. At a rate of up to 1,700 liters per second, operators pump and distribute the salty subsurface water into massive ponds and let 95 percent of brine water evaporate over 18-24 months. According to Dr. Ingrid Garcés, a professor of chemical engineering at the University of Antofagasta, around 2 million liters of water evaporate for every ton of lithium produced.

Evaporation Pond Method of Obtaining Lithium From Brine

This extraction and evaporation of water is negatively impacting the nearby communities – many of whom have lived in the area for millennia. Atacameño/Lickanantay and other Indigenous Peoples have developed agro-pastoral and irrigation practices suitable to the extremely arid environment, cultivating crops and raising livestock based on local knowledge. The rapid expansion of lithium after decades of intensive copper mining is depleting their groundwater resources. This is being done with uneven and improper consultation or consent under the principles of the International Labor Organization Convention 169 or the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The Puna de Atacama is also home to protected wetlands and extraordinary wildlife. The area’s lagoon oases host three species of flamingos, as well as endemic animals and unique microorganisms at risk of extinction. Lithium mining has already been shown to reduce the local populations of two of these three species of flamingos in the Atacama salt flat, and scientists suggest the impacts could grow more widespread as lithium mining expands.

Flamingos at Laguna Chaxa, Atacama Desert, Chile

Flamingo at Laguna Chaxa, Atacama Desert, Chile

Our report, co-authored with experts and researchers at the Plurinational Observatory of Andean Salt Flats (OPSAL), California State Polytechnic University, Pomona, and the University of California, Santa Barbara, highlights six conflicts involving communities who have been impacted by the lithium industry. We offer eight recommendations for communities, governments, and the private sector throughout the lithium-ion battery supply chain to avoid further damage to the Puna de Atacama:

- Respect and ensure free, prior and informed consent for Indigenous and local communities.

- Prioritize and incorporate Indigenous knowledge and science of local ecosystems.

- Strengthen environmental standards for mining operations and monitor activities.

- Regulate and monitor the use of brines and make data about local water resources available and transparent.

- Encourage, invest in, and implement alternative ways to obtain lithium (e.g. reusing or recycling batteries; geothermal direct lithium extraction).

- Ensure that companies throughout the battery supply chain require better practices from their suppliers.

- Apply longer-term solutions that reduce the need for new batteries, such as public transit, biking and walking.

- Enforce a moratorium on brine evaporation through application of the precautionary principle.

Brine evaporation in the Puna de Atacama is not a just, responsible, or even an efficient way of sourcing materials needed to address the urgent climate crisis. Better solutions exist and should be implemented as soon as possible.

James J. A. Blair is Assistant Professor in the Department of Geography and Anthropology at California State Polytechnic University, Pomona (Cal Poly Pomona). Dr. Blair is a former International Advocate for NRDC and has continued to work with NRDC’s International Program as a consultant, focusing on water protection and renewable energy in Chile.