Antibiotic use in livestock going up, up, up

This morning, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) released the latest report on sales of antibiotics for livestock use, that is, for use in meat and poultry production in 2013. The news follows the trends of the last few years, showing yet another increase in the numbers. Some lowlights:

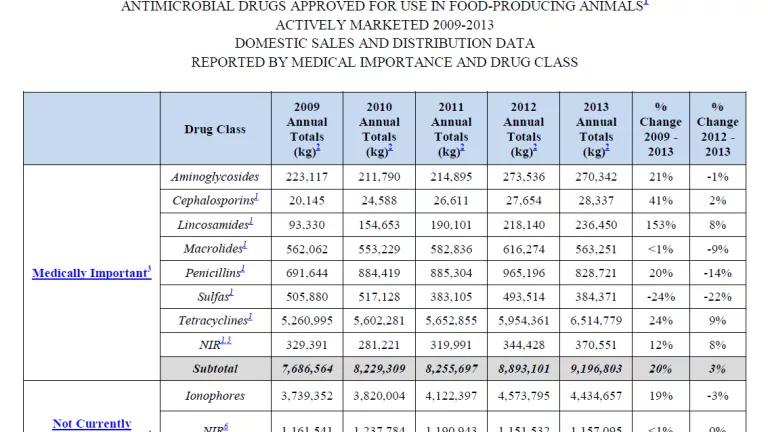

- Livestock antibiotic sales have gone up from about 16,115 tons in 2012 to a little over 16,300 tons in 2013, an increase of 1% (see Table 9).

- Use of antibiotic classes that are considered important in human medicine has increased even more, from about 9,800 tons to nearly 10,140 tons, an increase of 3% or 3 times the rate of the growth in overall livestock antibiotic use (see Table 10). Approximately 70% of medically important antibiotics sold in the US are sold for livestock use.

- About 95% of the medically important antibiotics sold are added to the food and water of animals, up slightly from 94% in 2012 (see Table 4). Since 2009, feed and water use has grown faster than any other kinds of uses, all of which have declined (see Table 11a).

Use of medically important antibiotics to produce meat and poultry is troubling because when the antibiotics are routinely given to herds and flocks of animals, some bacteria become resistant to the antibiotics. When these "superbugs" multiply and spread, they threaten people's health by contributing to the growing crisis of antibiotic resistance. Antibiotic-resistant infections can result in longer illnesses, more hospitalizations, the use of antibiotics with greater side-effects, and even death when treatments fail. Growing resistance also puts complicated medical procedures such as heart surgery, organ transplants, and chemotherapy in jeopardy, because they rely on the availability of effective antibiotics.

Overuse of antibiotics by both humans and in food animals contributes to the problem. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has been blunt about the seriousness of the threat, calling antibiotic resistance one of the five greatest health threats facing the nation.

The trend of increasing antibiotic use in meat and poultry production continues to throw into relief the inadequacy of the federal approach to antibiotic overuse in industrial meat and poultry production. Both the recent National Action Plan For Combating Antibiotic-Resistant Bacteria and the FDA's voluntary guidance, on which the National Action Plan relies, fail to stop the routine use of antibiotics in animal feed and water as a substitute for better animal husbandry. Even the pharmaceutical industry says that they don't expect FDA's guidance to make a significant dent in sales or use.

That's because FDA's guidance has a giant loophole. The FDA guidance seeks to stop the routine use of antibiotics in meat and poultry production to speed up animal growth but would not stop the overlapping routine uses of antibiotics to counter the disease risks that are exacerbated by crowded, stressful, and often unsanitary conditions. Because "growth promotion" and "disease prevention" uses overlap significantly, stopping only growth promotion uses would allow the continued routine use of antibiotics at low doses in the feed and water of large numbers of animals that are not sick. We need the federal government to do better with real action that stops meat and poultry producers from misusing these life-saving drugs, but no such action is on the horizon.

This is why we need leadership from the states. In California, Senator Jerry Hill has introduced a bill concerning the livestock use of antibiotics. That bill currently replicates the federal loophole. We are working closely with the Senator's office to close the loophole. Bills to stop the routine use of antibiotics in meat and poultry production have also been introduced in Maryland, Oregon, and Minnesota this year. In the absence of meaningful federal action, states need to step up and lead the way.