Montana’s Wolf Bounty Will Remain a “Fossil”

HB 279 was one of many bills proposed this session that all shared a single, scarcely veiled intention: kill more wolves.

A gray wolf stands at alert in the winter time.

Photo: CC0

A recent House Bill (HB 279) proposed to reimburse individuals for costs incurred while trapping wolves in Montana. The term “reimbursement,” in this case, was a glaring euphemism for “bounty,” which refers to a sum paid for killing or capturing something or someone. Modeled after a special interest group’s program in Idaho, this bill would have allowed monetary reimbursement for any number of unspecified costs (traps, vehicle fuel, whiskey…?) per wolf killed. Thanks to the groups and individuals who opposed it and the members of the Montana Legislature who voted it down, this bounty bill died on the Senate floor this week. HB 279 was one of many bills proposed this session that all shared a single, scarcely veiled intention: kill more wolves. At least for some, the proposal of HB 279 and other wolf killing bills raised awareness about how aggressively wolves are already managed. Current trends and scientific evidence show that we do not need more tools and incentives to trap and kill Montana’s wolves.

Montana hunters and trappers killed 315 wolves through public “harvest” in 2018—a new record. This represents between 30 and 40% of Montana’s total wolf population, but wolf mortality numbers don’t end there. Additional wolves are killed by wildlife management agencies because of livestock conflicts, struck by vehicles or trains and erased by poachers. In the last five years, an average of 60 wolves have been killed per year because of conflicts with livestock—in addition to public hunting and trapping. Wolves also succumb to natural causes, of course. Taking all forms of mortality together, it’s likely that nearly half of Montana’s wolf population perished in 2018.

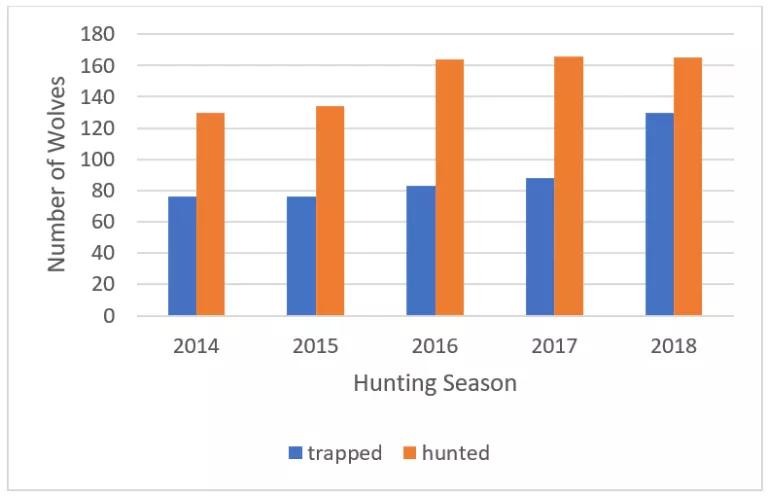

HB 279 would have helped to offset costs to trappers, but the number of wolves killed by trappers is already on the rise in Montana (see Figure 1), even though wolf populations have not grown over the last five years or so. In the most recent 2018-2019 season, trappers alone killed 130 wolves. That’s 42 more wolves killed by trappers this year than last year.

Wolves hunted and trapped in Montana 2014-2018

Montana wildlife management agencies employ individuals who are paid to trap wolves professionally, but the majority of trappers in the state choose to participate in wolf trapping as a hobby. A recent survey of trappers in the United States shows that trapping is considered a recreational activity in Montana, with the majority of respondents agreeing that trapping is not at all an important source of income to them. Just as any form of recreation (photography, hunting, rock climbing, etc.), individuals can choose to participate, or not, based on their values, enthusiasm, time, resources and other subjective factors.

Despite the stated intentions of HB 279 during recent legislative hearings, incentivizing wolf trapping is unlikely to significantly control livestock depredation. There is no credible evidence that the indiscriminate trapping of wolves yields real-world results in terms of reducing depredation, especially not in the long term. To the contrary, research indicates that indiscriminate removal of wolves through public “harvests” does not significantly reduce recurrent depredation, and removing wolves at random can even lead to increased conflicts. Also, according to the trapper survey mentioned above, only a small proportion of trapper’s efforts are targeted at “nuisance” wildlife, meaning most trapping is not done in response to livestock depredations or other conflicts. Overall, livestock losses due to wolves are extremely rare and have decreased in recent years, even as the wolf population has remained relatively stable in Montana.

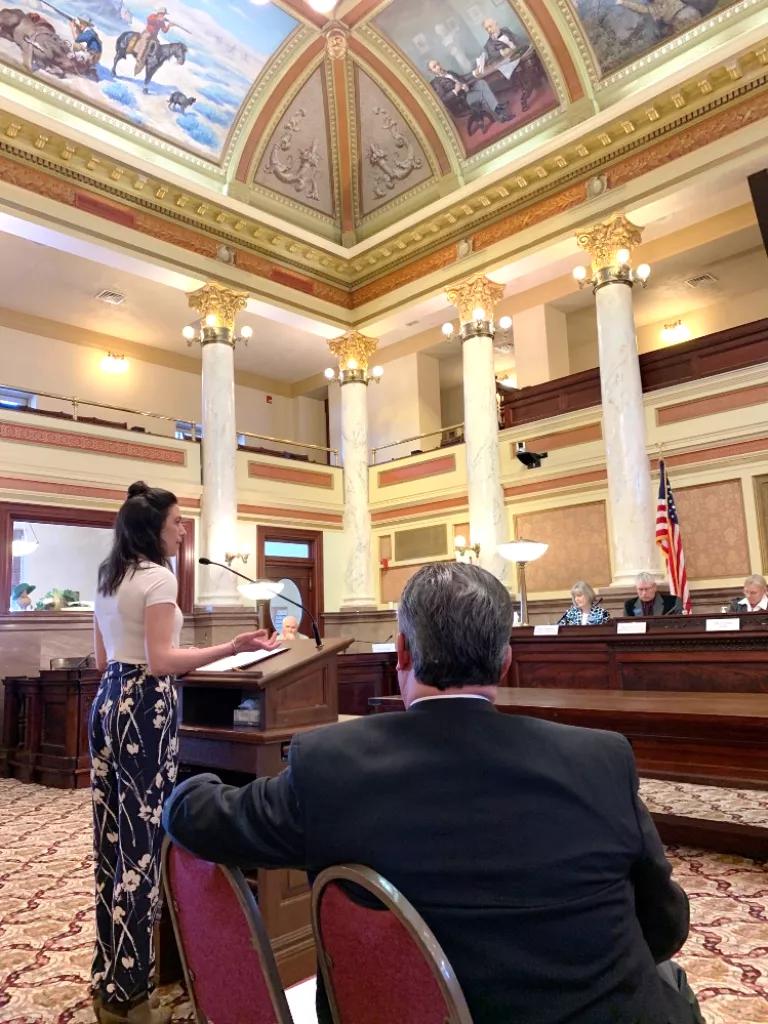

Jennifer (author) testifies on behalf of NRDC in opposition of HB 279 at the legislative hearing in Montana’s state capitol building, as the bill sponsor looks on from the audience.

In terms of protecting elk or other game animals, the predator-prey relationship is extraordinarily complex and incentivizing wolf trapping is simply too myopic an approach. Wolves can even boost the health of elk populations by controlling disease transmission through selective predation, though their beneficial services are often overlooked. Increasing wolf killing only serves to superficially appease frustrations and divert people’s attention away from the most significant impacts on elk distribution, which include habitat loss, hunting pressure and other factors that are primarily associated with human causes. HB 279, once again, implicated wolves as a voiceless scapegoat to excuse many of us from looking inward and confronting the myriad ways our own collective behavior is undercutting our most basic environmental needs and values.

We as a society have outgrown wolf bounty systems, because there are virtually no examples of bounties that have operated successfully in the long-run. Drawing on lessons from the wolf bounty programs of Canada, scientists have pointed out that bounties have failed to effectively reduce wolf populations, or to significantly increase game species. For these reasons, and because they are no longer publicly acceptable, bounties have been aptly referred to as a “legislative fossil.”[1] The failure of this bill confirms that there is no place for bounties in Montana’s wolf management.

[1] Theberge, J. B. (1973). Death of a legislative fossil: Ontario’s wolf and coyote bounty. Ont. Nat, 13, 32-37.