A New Reality: Climate Change and Lyme Disease in Canada

Blood-sucking horseflies, deer flies, mosquitoes, and ticks were an unavoidable part of my childhood in southern Canada. I still have a scar on my back from a hulking wood tick that managed to avoid detection for days before my mom pried it loose. But that wood tick, however gross, wasn’t a disease threat like blacklegged ticks are. Thanks to climate change, hard-to-spot blacklegged ticks are marching north of the U.S. border and spreading Lyme disease in their wake.

Black-legged ticks need four things to expand to a new area:

- Long-distance carriers, like migratory birds;

- Local non-human hosts for the ticks, like deer or mice;

- Suitable wooded or shrubby habitat for both the ticks and the hosts; and

- A minimum number of days with above-freezing temperatures, so the ticks have enough time to complete their life cycle.

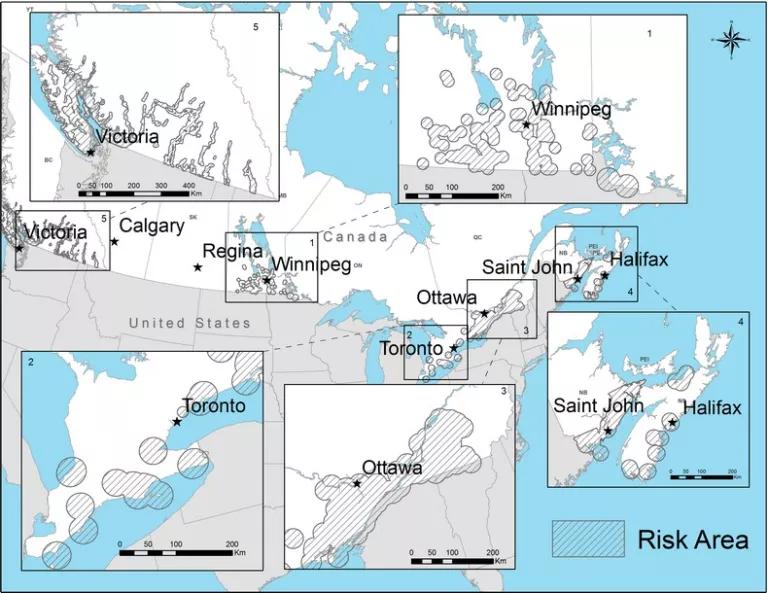

For decades, the only Canadian location that met the fourth criteria was Long Point Provincial Park in southern Ontario. That started to change in the early 2000s as southern Canada’s climate warmed. Now, black-legged ticks infected with the bacteria that cause Lyme disease are found in multiple areas of Ontario, Quebec, New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Manitoba. (British Columbia has a different species of tick that can carry Lyme-causing bacteria, but tends to get infected at lower rates.)

As a result, cases of Lyme disease have increased in Canada from 144 in 2009 to 917 in 2015. Most of that increase was due to a rise in locally-acquired infections, rather than travel-related infections.

Lyme disease is sometimes known as “the Great Imitator” because its symptoms can resemble anything from the flu to Alzheimer’s disease. That’s a problem, because the longer it takes to get treatment, the more severe the disease gets. I can attest that getting a prompt diagnosis is challenging even in the United States, which has a longer history of the disease and had 39 times more Lyme cases than Canada in 2015. Many Canadian doctors struggle to properly identify and treat a disease they’ve rarely or never seen in real life, leading to frustration among patients and even “medical tourism” outside the country.

The range of infected ticks in Canada will unfortunately continue to expand with or without action to address climate change. But the spread of ticks can be slowed, at least, by reducing the carbon pollution that’s warming our climate. Take New Brunswick, for example. Under continued high levels of carbon pollution, three quarters of the province could be occupied by black-legged ticks by 2080. With significant emission cuts, just half of New Brunswick could be affected.

Climate change has fundamentally altered the natural playgrounds I knew as a child. But there’s still time for us adults to cut back on carbon pollution and help other kids avoid that fate.