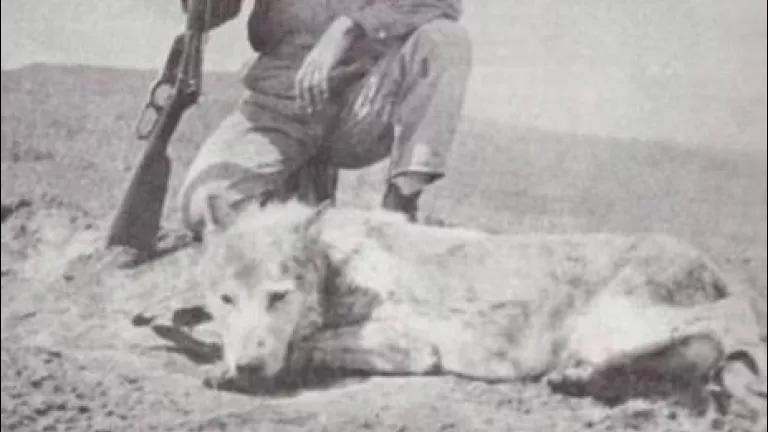

On Thanksgiving Day three hunters shot and killed a male grizzly in Grand Teton National Park. According to the Jackson Hole News and Guide, the three men were hunting in heavy timber along the east side of the Snake River between Schwabacher’s Landing and Teton Point Overlook, when the bear charged them. Investigating park officials discovered a cow elk carcass near where the shooting took place. The death was the 51st grizzly bear mortality in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem in 2012.

The hunters who shot the grizzly were participating in the park’s Elk Reduction Program—a hunting season made legal by the enabling legislation that authorized the park’s expansion in 1950.

I’m a hunter. Have been all my life. First helped my dad quarter and pack out an elk when I was three. There are many reasons why I hunt, and why I support and encourage others to hunt. It gets us outside, gets us back into the mountains, reconnects us with wild places and wild animals and wild weather. It’s great exercise. It brings families together. And there isn’t any healthier, environmentally friendly meat than wild game.

But there are places we shouldn’t be hunting, and Grand Teton National Park is one of them. For one, it poses a safety risk to the park’s many fall visitors—hunters and non-hunters alike. It places large numbers of people, many of whom are carrying rifles, in relatively confined areas, often with poor visibility. Hunters leave gut piles in hard-to-see places, which attract hungry, defensive, hard-to-see bears (often mothers with cubs). Last year, a hunter was attacked and injured by a grizzly in the same area as this year’s incident.

It is also bad for Yellowstone-area grizzlies, a subpopulation protected by the Endangered Species Act that relies on the intact, protected ecosystems within Grand Teton and Yellowstone parks to continue to recover to a sustainable population size. The bears are becoming habituated to finding and claiming hunters’ gut piles year after year—and learning to hear rifle shots as “dinner bells.” This can lead to conflicts between bears and hunters over carcasses; conflicts which, all too often, result in bear deaths.

Park officials and biologists say that the Elk Reduction Program (and, apparently, the risks it poses to humans and grizzlies) will be necessary as long as winter feeding on the nearby National Elk Refuge continues to result in large numbers of elk migrating north to the Park in the spring. But this rationale is disturbing because it justifies a bad practice with one that is even worse.

Every winter, the National Elk Refuge, along with Wyoming’s 22 other state-operated feedgrounds, provide hay and alfalfa pellets to more than 20,000 elk to improve winter survival rates, thereby maintaining an artificially high population. (Contrast this practice with, for example, Montana’s, which makes it a crime to provide supplemental feed attractants to game animals. See Montana Code Annotated section 87-6-216.)

Feedground operators and many Wyoming residents support the practice because of the revenue these elk herds generate for local communities through tourism and hunting. But feedgrounds foster unnaturally dense concentrations of elk, which results in a variety of problems, the most serious of which is increased infectious disease transmission. For example, 30% of the elk using Wyoming’s feedgrounds are infected with brucellosis. Elk in these unnatural conditions are also more susceptible to scabies, foot rot, and other afflictions.

Most concerning, though, is Chronic Wasting Disease (CWD), a highly contagious neurological disease that causes degeneration in the brain tissue of affected animals. Basically, it is the cervid (deer, elk, moose) equivalent of mad cow disease. It is a horrible disease, which causes animals to literally waste away and die within 1 to 4 months of exhibiting symptoms. Those symptoms include listlessness, emaciation, drooling, repetitive walking in a set pattern, and constant thirst. CWD is always fatal. And while CWD prevalence in free-ranging elk herds is only 1-3%, its prevalence in captive herds, whose densities more closely match those of feedground elk, has been recorded as high as 59%.

While it has not yet reached Wyoming’s feedgrounds, it has been documented in captive and free-ranging elk populations to the south and east. And it is heading northwest. It is transmitted through infectious agents called prions, which can spread either directly from infected animals, or indirectly from the soil (while animals are browsing). Prions enter the soil through blood, saliva, feces, urine, and even antler velvet. Once in the soil, prions can persist and remain infectious (and deadly) for years. The disease has a long incubation period of several months to years, meaning it can be transmitted widely throughout a herd before the first physical symptoms are detectable.

The point here is simple: feedgrounds are bad news—for people, elk, bears and others. So why haven’t they been stopped?

In 2008, a coalition of conservation groups filed suit in federal court to ask that the practice of feeding elk on federal land in Wyoming be phased out and ended within five years. Eventually, the case made it to the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals, where, in 2011, a panel of judges ruled that the practice must eventually come to an end. The court recognized that “[t]here is no doubt that unmitigated continuation of supplemental feeding would undermine the conservation purpose of the National Wildlife Refuge.” (Opinion, p. 10). The Court refused, however, to impose any deadline, deciding that a mandatory stop date was not necessary so long as the agencies involved were committed to eventually phasing out and ending the supplemental feeding—which the court believed they were.

Though the court’s language and decision were encouraging, the feeding programs will remain in place for the foreseeable future. And because the lawsuit only challenged feeding practices on federal lands, the court’s decision does not affect the remaining 22 state-operated feedgrounds.

In the name of elk and other wildlife, let’s hope that the agencies, operators and feedground supporters move forward as quickly as possible to end this unnecessary and counterproductive practice. Let’s hope they remember that the longer they wait, the closer CWD creeps toward northwestern Wyoming, the greater the odds that another fall visitor to Grand Teton National Park will be injured, and the higher the likelihood that another park grizzly, just trying to be a bear, will die.