The Fishing Industry on Acid

Ocean acidification will hit coastal communities like these the hardest.

The economy of New Bedford, Massachusetts, ground to a halt in the 1980s after a fleet of high-tech boats fished the region’s once-plentiful cod to exhaustion. Thirty years later, the city is experiencing a renaissance. Scallops have replaced cod, business is booming, and the local economy is riding the wave. Statewide, the value of the scallop catch has risen more than sixfold since 1993—part of the $1 billion–a–year U.S. shellfish industry.

“I would never have dreamed that things would be as good as they are,” a New Bedford scallop captain told The Boston Globe in 2013. “Ten years ago even, I would have never believed we’d be in this condition.”

What could possibly go wrong now? Plenty. A new study suggests that New Bedford is one of many U.S. coastal towns on the precipice of economic collapse—even if they don’t know it yet. The reason: ocean acidification.

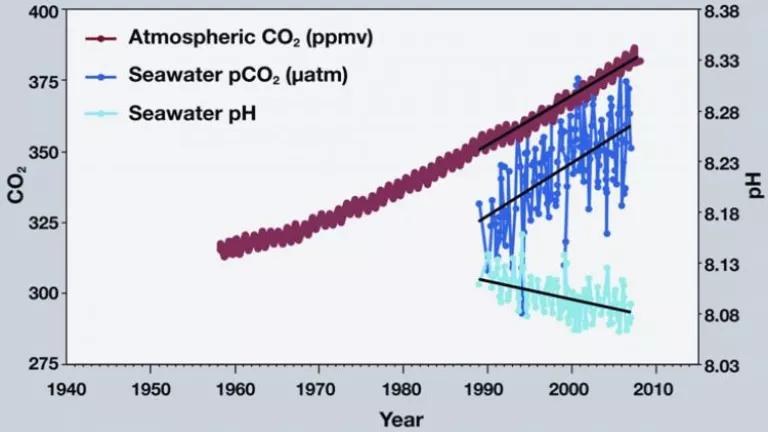

Acidifying oceans are a result of carbon pollution. As carbon dioxide levels in the atmosphere increase, more of that CO2 dissolves in seawater. The dissolved gas increases the acidity of ocean. Approximately a quarter of the CO2 emitted by humans ends up in the sea, and scientists estimate that the pollution is causing oceans to acidify faster than they have in 300 million years.

As this new report shows, ocean acidification threatens coastal communities in 15 U.S. states on both coasts. (Get fact sheets for specific threats to each of those states.)

The social and economic impacts of ocean acidification will not be evenly distributed, according to a new paper out today in Nature Climate Change. The study was led by Lisa Suatoni and Julie Ekstrom, scientists in the oceans program at NRDC (disclosure), along with collaborators from the University of California-Davis, the Ocean Conservancy, Duke University, and nine other institutions. “We mapped local factors that exacerbate ocean acidification,” says Suatoni, “and we found increased vulnerability in places like the Louisiana Bayou, Virginia, and New Bedford.”

Why would ocean acidification hit some areas harder than others? Water pollution is one factor. Rivers carry nutrient runoff—much of it in the form of manure from farms and sewage plants—into the Gulf of Mexico and the Chesapeake Bay, where that pollution feeds massive algal blooms. The bacteria feeding on the dead algae not only create dead zones by sucking up oxygen but also release large amounts of carbon dioxide as part of their metabolic process. Those CO2 molecules, combined with the carbon from the atmosphere, intensify ocean acidification in these areas. Think of them as acidification hot spots.

Economics can also make a place especially vulnerable to ocean acidification. This is where New Bedford comes in. The town is now almost completely reliant on scallops to sustain its economy, with the mollusks accounting for 80 percent of the city’s catch as of 2012. Ocean acidification puts those creatures, as well as oysters, clams, and other shelled mollusks, at risk.

How? Carbon dioxide reduces the number of calcium carbonate ions in seawater, which makes it difficult for marine life, such as lobsters, snails, and shrimp, to build calcium-based shells and exoskeletons. (“Imagine trying to build a house while someone keeps stealing your bricks,” writes journalist Elizabeth Kolbert in her book The Sixth Extinction.) When acidification becomes extreme, the water literally dissolves the animals’ shells.

This isn’t just a theory or a prediction: Marine biologists have already observed how carbon dioxide pollution can wipe out calcifying species. There are virtually no corals, for example, near carbon dioxide vents on the ocean floor. The same thing will happen to starfish, sea urchins, clams, oysters, and scallops in increasingly acidic areas. That wouldn’t just send shock waves up the food chain—it would also mean economic doom for places like New Bedford.

The acidification of the ocean won’t stop any time soon—the process is already far advanced, and the sea can’t neutralize the carbon dioxide nearly as fast as it is being absorbed. It will likely take thousands of years for the sea’s pH to return to normal. Governments around the world have shown little appetite for rapid carbon pollution reductions. But there are steps we could take right now to ease the burden on vulnerable communities—at least for a while.

Reducing nutrient pollution would be a good start. State and federal governments could enforce limits on how much waste can be released into our nation’s waterways. That would help slow acidification in places like the Chesapeake Bay and the Gulf of Mexico. The NRDC scientists also suggest diversifying fishing fleets and raising shellfish away from souring waters, as well as the development of early warning systems that will tell communities when their waters become corrosive.

Another potential strategy for the fishing industry is something called “facilitated evolution.” Natural genetic variation makes some scallops, oysters, and clams more tolerant of acidity than others. By selectively breeding those organisms, we might be able to keep some populations viable in a changing environment. Such mollusks might sound like Frankenfood, but they’re not—we’ve been selectively breeding animals and plants for millennia. It’s how we turned kale into cauliflower, and how we invented peaches, corn, and cows.

So perhaps it’s time to consider the scallop—New Bedford may depend on it.

This article was originally published on onEarth, which is no longer in publication. onEarth was founded in 1979 as the Amicus Journal, an independent magazine of thought and opinion on the environment. All opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies or positions of NRDC. This article is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the article was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the article cannot be edited (beyond simple things such grammar); you can’t resell the article in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select articles individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our articles.

Biodiversity 101

Demand for Sustainable Seafood—Gone Overboard?

Neonicotinoids 101: The Effects on Humans and Bees