Don't Mess with the Bull Moose

News flash: Our public lands already belong to “the people.” And we have a he-man Republican rancher to thank for it.

Given that the armed occupiers of the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge have holed themselves up in the facility’s visitor center for almost a week—and given that they’ve indicated their willingness to remain there indefinitely, according to the group’s spokesmen—perhaps they should take advantage of the many entertaining and educational diversions to be found in the visitor center’s gift shop.

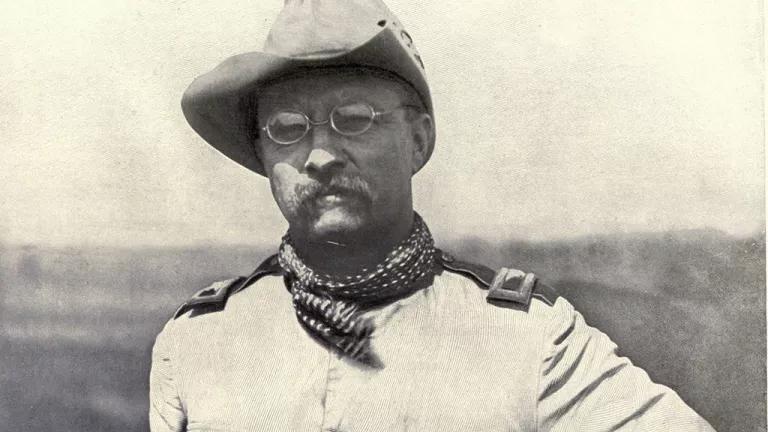

Should any biographies of Theodore Roosevelt happen to be on hand amid all those 2016 wall calendars and wooden bird whistles, the protesters might well enjoy reading about their fellow cattleman, arguably the manliest of manly-man Republican icons in our nation’s history: a lawman, a navy man, a cavalryman, and a hunting man, in addition to our 26th president. A man who once captured and stood guard over a band of boat thieves for nearly 40 hours until law enforcement arrived, reading Tolstoy to himself in order to stay awake. A man who once gave a 90-minute speech with a newly lodged bullet in his chest before going to the hospital.

During his presidency, Roosevelt created the Malheur National Wildlife Refuge in 1908, turning unclaimed government property into one of more than 50 “bird reservations.” In previous centuries, the stewards of this land were the Paiute people, who had been ordered to leave in the 1870s as more and more settlers came to the area. These vast tracts of pristine land, which had never been owned privately, would eventually become the physical foundation for our current, 150-million-acre National Wildlife Refuge System. In May of that same year, he called a number of the nation’s governors to the White House for a pivotal conference in which he eloquently articulated the case for placing large parcels of undeveloped rural land under federal protection.

His pitch to the assembled governors included this statement:

We have become great because of the lavish use of our resources, and we have just reason to be proud of our growth. But the time has come to inquire seriously what will happen when our forests are gone; when the coal, the iron, the oil, and the gas are exhausted; when the soils shall have been still further impoverished, and washed into the streams, polluting the rivers, denuding the fields, and obstructing navigation.

This rhetorical line of “inquiry” was in reality the policy rationale for a sweeping set of acts and executive orders that would, in the aggregate, end up protecting nearly 230 million acres of land comprising hundreds of national forests, bird and game preserves, national parks, and national monuments. It also informed the mandate of the fledgling U.S. Forest Service, which had been established only three years earlier under Teddy Roosevelt’s direction. By the end of his administration, America’s 26th president had placed more land under federal protection than every one of his 25 predecessors combined.

And he accomplished all this, remember, as a serious cattleman and Republican. The story of tensions between federal land managers and disgruntled western ranchers is nothing new; it’s been going on for centuries. To hear some folks tell it, the story pits a rapacious and inept Washington, D.C., bureaucracy against the common-sense wisdom of locals who have been working on (and living off) western lands for generations, and whose cultures and livelihoods are inextricably tied to its copious bounty and responsible stewardship.

In that telling, the story becomes a kind of populist romance, brimming with many beloved tropes that Americans have absorbed over the two and a half centuries we’ve been analyzing and celebrating our own exceptionalism. The rugged individualist standing up to the corrupt, effete machine. The soulful underdog, reluctantly but resolutely taking on the soulless establishment. The frontier spirit versus the dreaded “Washington mind-set.”

But it’s also so ridiculously reductive as to constitute a lie. And were he alive today, Teddy Roosevelt would be the first to call anti-government ranchers out on that lie. If he needed examples to illustrate and personalize his points, he could easily pull them from his own life experience. In his 1910 memoir, Hunting Trips of a Ranchman, he wrote grippingly and horrifyingly of how a combination of harsh weather, wildfires, and massive overgrazing rendered the ranchlands of the Dakota Badlands—including his own 5,000 acres—utterly worthless for raising cattle. At one point he relayed the image of starving cows climbing giant snowdrifts during the blizzard-filled winter of 1886–87, desperately trying to eat the small twigs off trees. In that unregulated libertarian “paradise,” at some point there was simply no edible grass left for the animals to graze on. After the thaw, their bodies were found lodged in the tree branches.

Experiences like that one shaped Teddy Roosevelt indelibly and made him fully appreciate the relationship between the words conserve, conservation, and conservative. But make no mistake: Were he alive today and directing our nation’s public-lands policy, he’d be fighting regularly with those on the political right and the left. Roosevelt’s vision for land management and conservation was rooted at least partially in his belief that public lands could, through responsible stewardship at the federal level, yield consumable resources perpetually over future generations. (It was a vision that frequently put him at odds with his friend and camping partner, the philosopher-naturalist John Muir.)

But in a way, that’s why it would be so great to have him back, even for just a little while, at this weird and unsettling moment in our national dialogue on land use. Those who would angrily demand that the land be “returned to the people” may actually think they’re defending a sacred conservative principle and upholding a noble populist tradition when they shake their fists and scream their slogans. But in reality, they’re doing no such thing. These lands are already with the American people—in the form of the representative government that we, the people, continually construct and reconstruct with our votes during national elections.

That’s where they must stay if they’re to remain ecologically healthy, accessible to the public, sustainable for future generations, and (yes) good for cattle grazing. We can continue to argue amongst ourselves, vigorously and vehemently, over what we think of as the best ways to manage these lands. Those arguments are certainly worth having. But we—meaning all of us—deserve to take part in them.

This article was originally published on onEarth, which is no longer in publication. onEarth was founded in 1979 as the Amicus Journal, an independent magazine of thought and opinion on the environment. All opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies or positions of NRDC. This article is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the article was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the article cannot be edited (beyond simple things such grammar); you can’t resell the article in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select articles individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our articles.

A Trailblazer for Tribal Sovereignty

Biodiversity 101

Five Indigenous Poets Explore Loss and Love of their Native Lands