The Long, Long Battle for the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

For decades, politicians have vacillated between protecting Alaska’s refuge as one of the last unspoiled places on earth and plundering it for oil.

Steve Hillebrand/USFWS

Before the creation of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in 1980, conservationists fought for many decades to protect these lands that sit relatively untouched at the northeastern edge of Alaska. And for just as long, oil and gas interests have been trying to drill the refuge’s coastal plain—an area that the Gwich’in people have called “the sacred place where life begins.”

The refuge’s 19.6 million acres are home to an abundance of wildlife—musk oxen, wolves, caribou, and polar bears—and are the summer breeding grounds for millions of birds that migrate here from six continents and all 50 states. Its lands and waterways are also vital to the Gwich’in and other local Indigenous communities who have relied on these rich ecosystems for millennia. The debate over what to do with this landscape has raged for nearly a century, but now, in the midst of a climate crisis that’s wreaking havoc at every latitude but warming the poles at astonishing rates, there’s broad consensus that drilling the Arctic for fossil fuels is beyond a terrible idea.

President Joe Biden has temporarily halted oil and gas activity in the coastal plain, but the moratorium falls short of permanent protection of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Only Congress can do that. And if the political history of the refuge is any indication, the fight is far from over. Here’s a quick recap.

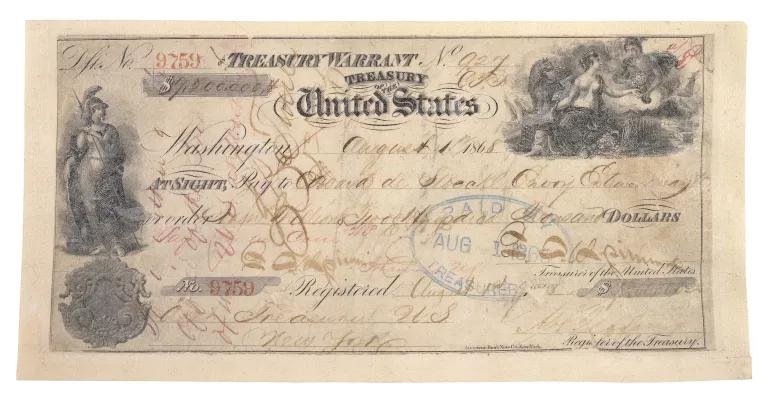

The check used to purchase almost 600,000 square miles of land from the Russian government

March 30, 1867

The United States buys Alaska (previously known as “Russian America”) for $7.2 million. Even then, many politicians saw dollar signs in the snow. At the time, the New York Tribune wrote: “[Alaska] includes a great number of islands, and is of the highest importance as a naval depot, and for strategic purposes. It is a valuable fur country, and embraces a vast section of territory, the possession of which will influence in our favor the vast trade of the Pacific…The fisheries are very extensive, but the principal commercial wealth of the country is in its fur trade, which would, henceforth, be altogether controlled by American merchants.”

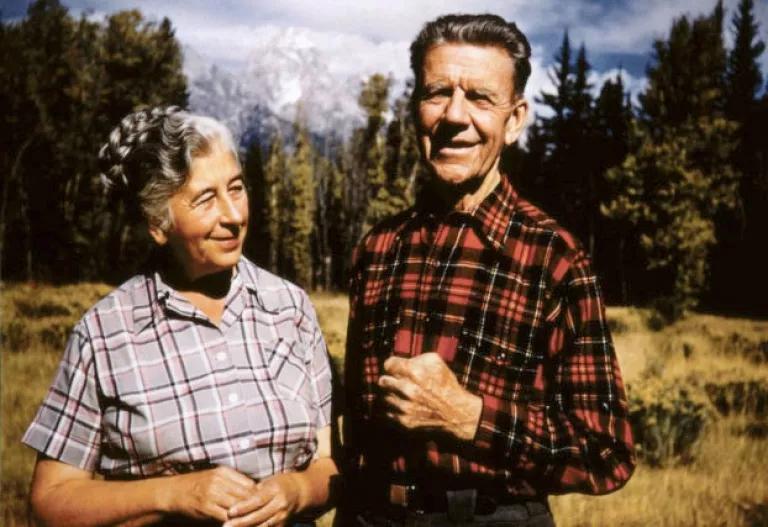

Mardy and Olaus Murie on their ranch near Moose, Wyoming, 1953

Credit: Steve Hillebrand/USFWS

Summer 1956

The Wilderness Society’s president, Olaus Murie, and his wife, Mardy, conduct an expedition to Alaska’s Brooks Range with biologists George Schaller and Robert Krear. After months of surveying the land and studying the region’s wildlife, the Muries began pushing for federal protections of the Alaskan Arctic. The couple was later instrumental in the passing of the 1964 Wilderness Act.

North of Atigun Pass, looking into the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

Lisa Hupp/USFWS

December 6, 1960

Public Land Order (PLO) 2214 establishes the National Arctic Wildlife Range. Industry and environmental interests had been feuding over the fate of the region since the late 1920s, when conservationist Robert Marshall began campaigning to set aside northern Alaska as permanently wild. People like George L. Collins and Lowell Sumner of the National Park Service argued that the best use of the land was purely for wilderness and recreation, but both military and business leaders wanted the land for oil and gas exploration. (In his 1961 cautionary farewell speech about the burgeoning “military-industrial complex,” President Dwight Eisenhower warned against “plundering…the precious resources of tomorrow.” Perhaps the conflict in northeastern Alaska was on his mind.) In PLO 2214, Secretary of the Interior Fred Seaton set aside 8.9 million acres in northeast Alaska. The order, issued one year after Alaska became a state, withdrew the area from “all forms of appropriation under the public land laws, including the mining but not the mineral leasing laws.” Because mineral leasing includes fossil fuels, that order kicked the oil can down the road.

President Jimmy Carter after signing the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, in Washington, D.C.

Jimmy Carter Presidential Library

December 2, 1980

President Jimmy Carter signs the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act, expanding the range to 19.3 million acres and renaming it the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. The law mandated wildlife studies and an oil and gas assessment of the coastal plain. In a compromise with the lame duck president, the law noted that no exploratory drilling or production could occur without further congressional action. That provision, giving Congress the power to decide, is what turned the fate of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge into a decades-long saga.

The coastal plain between the Dalton Highway and the Arctic Refuge

Lisa Hupp/USFWS

April 20, 1987

Secretary of the Interior Donald Hodel recommends that Congress open the coastal plain to oil and gas development. The U.S. Department of the Interior estimated a 19 percent chance of finding economically recoverable oil, and, if found, the mean amount would be 3.23 billion barrels (a 200-day supply of oil at the time of the congressional report’s publication). At the time, however, only one exploratory well had been drilled in 1985 by Chevron and BP, and the companies didn’t publicly state what, if anything, they discovered. (ARCO did find oil 16 miles offshore in federal waters.)

Cleanup following the Exxon Valdez disaster at Quayle Beach on Smith Island in Prince William Sound, Alaska, August 7, 1989

Alaska Resources Library & Information Services (ARLIS)

March 24, 1989

The Exxon Valdez runs aground, spilling at least 11 million gallons of crude oil into Prince William Sound. The cleanup demonstrated the difficulties of remedying a major oil spill in Alaskan waters, which are considerably tamer than those of the Arctic, and the extreme limitations of available technology. Crews used high-pressure, hot-water washers to blast oil off of rocks along the shore, a tactic that badly damaged plants and animals, with long-lasting impacts. The crude killed more than 250,000 seabirds, and sea otter populations took 25 years to return to pre-spill levels. Herring and other fish still have not recovered. Eight days prior to the disaster, a Senate committee had approved oil production on the coastal plain, but the spill increased scrutiny on Arctic National Wildlife Refuge drilling.

President Bill Clinton with (from left) Senate Majority Leader Bob Dole, Vice President Al Gore, and House Speaker Newt Gingrich during a budget meeting, 1995

Clinton Presidential Library and Museum

December 6, 1995

President Bill Clinton vetoes the Balanced Budget Act. As the shock of the Exxon disaster faded, pro-oil legislators attempted to open the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to drilling by bypassing conservation-minded filibusters. After Republicans took control of Congress in 1994, they passed an appropriations bill that could not be filibustered. President Clinton, however, vetoed the bill, dealing a blow to House Speaker Newt Gingrich’s “Contract with America.” Protecting the refuge was on President Clinton’s list of 82 (!) reasons for the veto, along with his objections to over-aggressive tax cuts and threats to Social Security and Medicare. This was the closest oil companies had gotten to the coastal plain thus far.

Alaska senator Ted Stevens with Vice President Dick Cheney, September 2005

Office of Senator Ted Stevens

December 21, 2005

A filibuster blocks the opening of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to drilling. The year after President George W. Bush’s re-election was the high-water mark of his attempts to allow the oil industry to exploit the refuge’s coastal plain. As Congress attempted a decade earlier, Republicans included a provision in a budget bill, only to be thwarted by stiff resistance from approximately 20 lawmakers in their own party who refused to support drilling in the refuge. Desperate to deliver on promised spending cuts, Alaska Senator Ted Stevens tried a risky gambit by moving the provision out of the budget bill and into the Defense spending bill. It proved a tactical error, because the Defense bill was vulnerable to filibuster, and that’s just what happened. An infuriated Stevens railed at his colleagues, “We know this Arctic. You don't know the Arctic at all,” before vowing to open the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge “however long” it took. When Stevens left office in 2009, he was the longest-serving Republican in Senate history, but he never managed to get drills into the refuge.

Canning River on the coastal plain in the Arctic Refuge

Lisa Hupp/USFWS

March 13, 2008

The year before he leaves office, Stevens, along with fellow Alaska Senator Lisa Murkowski, tries a different tack, introducing a bill that would open the coastal plain to drilling only if the price of oil should remain at $125 per barrel or above for five consecutive days. Murkowski even sweetened the pot by dedicating the royalty revenues to the Low Income Home Energy Assistance Program and child nutrition. Although oil prices exceeded that threshold shortly after the bill’s introduction, peaking at more than $136, Murkowski’s colleagues weren’t interested in her contingency wheeling and dealing.

The Porcupine caribou herd crossing a river in the Arctic Refuge

Gary Braasch/National Wildlife Federation, CC BY-NC-ND 4.0

January 25, 2015

Shortly after the introduction of two bills to the House and Senate that would designate the coastal plain as wilderness, the Department of the Interior recommends designating 12 million more acres of the refuge, including the coastal plain, as wilderness. The DOI started planning to manage the lands as such, and President Barak Obama called on the then-Republican-led Congress to move forward with the designation to make those protections permanent.

The House of Representatives wing at the Capitol in Washington, D.C.

Joel Carillet/iStock

February 26, 2016

The House of Representatives votes on the Arctic Refuge Wilderness bill. While the legislation did not pass it, this was the first time Congress had ever voted on a wilderness bill for the refuge.

The Brooks Range in the Arctic Refuge

Cathy Hart/Alaska Stock via Alamy

December 20, 2017

In a 180-degree reversal from the Obama administration’s proposed protections for the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, the Trump administration puts forward a $1.5 trillion tax bill that would, for the first time ever, open the area to oil and gas drilling. Despite the fact that the numbers of the tax plan—which skewed heavily toward benefiting the wealthy and padding the profits of polluters—didn’t add up, it passed with full Republican support and set in motion the most critical threat to the refuge yet.

A polar bear mother and her cub in the Arctic Refuge

Steven Kazlowski

September 12, 2019

The Trump administration releases its final environmental impact statement (EIS) for an oil and gas leasing program in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge—what NRDC staff attorney Garett Rose calls “a slapdash attempt to skirt the environmental laws it purports to satisfy.” The National Environmental Policy Act requires the EIS to consider the impact drilling would have on wildlife and Indigenous communities as well as alternative approaches that would minimize damage to the land, but the EIS did neither. Just as with the “half-baked” draft statement, Rose said the EIS showed that the administration was simply trying to fast-track drilling—a goal Trump adopted after he learned of other Republican presidents’ failed attempts to drill the refuge.

Snow-covered tracks left by a 3-D seismic survey conducted in the winter of 2017–18 on public lands along the Arctic Refuge’s western boundary

M. Nolan/Ecological Society of America, CC BY 4.0

August 17, 2020

The Department of Interior officially opens 1.5 million acres of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge’s coastal plain to the oil and gas industry. The unprecedented move threatened to imperil the Gwich’in people and other Indigenous communities, while exacerbating both the climate and biodiversity crises. “Sloppy and unpredictable” was how Bernadette Demientieff, executive director of the Gwich’in Steering Committee, characterized the decision and the final environmental impact statement that informed it. “The federal government did not meaningfully engage with us, and they left out Gwich'in communities in Alaska and Canada. As a result, people that will be negatively affected were never given a voice.”

Neetsa’ii Gwich’in leader Sarah James (center) from Arctic Village, Alaska, marching in Washington, D.C.

Yeimaya via Flickr, CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0

August 24, 2020

Indigenous and environmental groups sue the Trump administration for its decision to open the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge to oil and gas drilling. The two lawsuits—one brought by the Gwich’in Steering Committee, along with national and Alaska-based groups, and a second brought by NRDC and other national environmental groups—argued that the administration’s leasing plan violated several federal laws, including the National Environmental Policy Act, the Endangered Species Act, the National Wildlife Refuge System Administration Act, and the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act.

The Brooks Range in the Arctic Refuge

iStock

January 6, 2021

The federal government holds its first-ever oil and gas lease sale for the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. Only three bidders showed up. The sale generated $14.4 million in bids—a far cry from the $1.8 billion that the Trump administration estimated the lease sales would bring in over their 10-year span in order to offset the 2017 tax plan. The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act requires a second lease sale by the end of 2024, and only Congress can definitively prevent this by amending or repealing the leasing provision in the 2017 law.

A muskox grazing in the Arctic Refuge

Katrina Liebich/USFWS

January 20, 2021

President Biden, on his first day in office, issues several pro-climate executive orders, including one that places a moratorium on oil and gas drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. In its explanation for the moratorium, the Biden administration cited the “legal deficiencies underlying” the previous administration’s leasing program in the refuge, “including the inadequacy of the environmental review required by the National Environmental Policy Act.”

A river flowing north from the Brooks Range across the coastal plain in the Arctic Refuge

Lisa Hupp/USFWS

February 4, 2021

Congress reintroduces the Arctic Refuge Protection Act to restore protections to, and prevent oil and gas development in, the coastal plain. (The House of Representatives had passed a previous iteration of the act in September 2019, marking the first time the House took action to protect the refuge.) “These bills are critical to protecting the Arctic Refuge from industrialization forever,” Rose said after the reintroduction. “These measures recognize—and neutralize—the unacceptable threat that the 2017 tax bill posed to this ecological crown jewel.”

The Hulahula River in the Arctic Refuge

Alexis Bonogofsky/USFWS

June 1, 2021

The Interior Department formally suspends oil and gas drilling leases in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge until the finalization of its environmental review of the leases—a process that will include a legal review of the Trump administration’s decision to grant the leases in the first place. Chief Dana Tizya-Tramm of the Vuntut Gwitchin First Nation expressed his appreciation for the news but knows the fight is far from over, saying, "Our work will not stop until our lands are permanently protected through legislation.”

September 6, 2023

The Biden administration formally canceled the last remaining Trump-era leases for oil and gas drilling in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge that it had suspended two years prior. The decision affected seven leases, which covered 365,000 acres of the Coastal Plain. NRDC President and CEO Manish Bapna praised the move, noting: “It’s long past time to stop sacrificing irreplaceable wildlife habitat and Indigenous lands to deepen our dependence on the fossil fuels driving the climate crisis. This puts our future first. It protects the realms of birthing caribou and migratory birds. It safeguards the lands that the Gwich’in people rely on for their livelihood.”

This story was originally published on June 8, 2022 and has been updated with new information and links.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

Alaska’s Tongass National Forest Gets the Protections It Deserves

Crushing Alaska’s Pebble Mine

Alaska Natives Lead a Unified Resistance to the Pebble Mine