The Uinta Basin Railway Would Be a Bigger Carbon Bomb Than Willow

The project could sabotage U.S. climate goals, send oil-filled trains along the Colorado River, and pollute the air from Utah to the Gulf Coast.

The 88-mile Uinta Basin Railway—which would connect to common carrier lines like the one shown here near Price, Utah—would carry crude oil through tribal lands and a national forest.

Rick Bowmer/AP Photo

UPDATE: On January 17, 2024, the U.S. Forest Service rescinded its approval of a permit that would allow the proposed Uinta Basin Railway to cut through a roadless area in Utah’s Ashley National Forest. While the decision dealt another serious blow to the project, the agency may reverse it yet again if proponents address the inadequacies within the railway’s environmental impact statement.

The oil lying beneath the Uinta Basin isn’t your typical black gold. It can be black, but also yellow and waxy, and to transport it from this remote corner of northeastern Utah, the oddball crude requires heated tankers—otherwise, it would solidify into the consistency of shoe polish. So, for the past 80 years or so, despite high demand for oil and the basin’s large reserve, business here has been relatively slow, with most of the oil being sent only to specialized refineries in nearby Salt Lake City.

But over the past decade, seven counties in the state have been looking to cash in on the Uinta’s reserves. The Seven County Infrastructure Coalition proposed building a new railway that would make the basin’s oil available to large numbers of new customers by sending the oil to refineries on the Gulf Coast.

All in all, this fossil fuel project is a terrible idea for the usual reasons: new and unnecessary risks to local watersheds, public health, and the global climate. These include derailments that could spark wildfires or dump crude into the Colorado River; worsened air pollution within Gulf communities; and an insane amount of carbon emissions at a time when the federal government is trying to dramatically slash greenhouse gas emissions over the next six years to rein in the climate crisis.

On a positive note: In August, a federal judge voided a permit needed for the railway’s construction, citing a failure of the Surface Transportation Board (STB) to adequately analyze the project’s potential environmental impacts. The U.S. Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia then upheld that decision earlier this month.

It’s a huge win, one that could delay the Uinta Basin Railway (UBR) for years, but NRDC senior advocate Josh Axelrod cautions, “The threat persists—the proposal is still out there.” The coalition is also busy with other efforts to ramp up the amount of crude oil coming out of Utah.

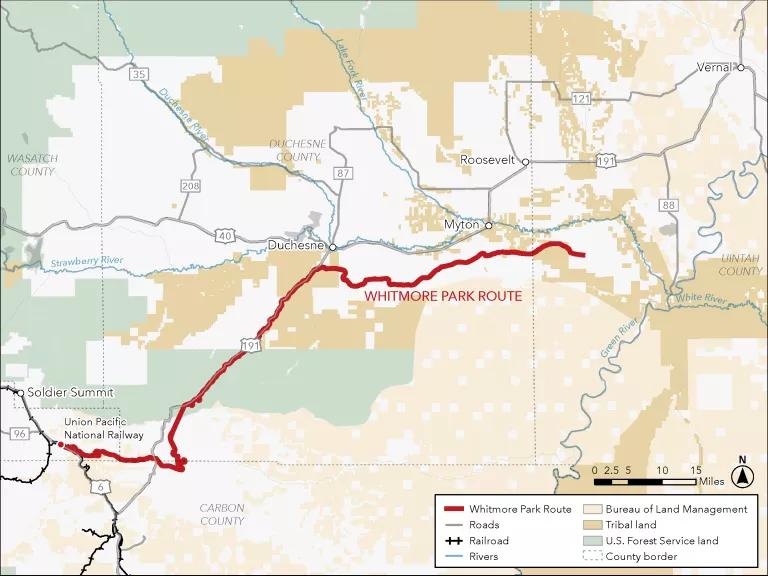

The Whitmore Park Route is the final pathway for the proposed Uinta Basin Railway.

https://uintabasinrailway.com/

What is the Uinta Basin Railway?

The proposed railway would run 88 miles between the Uinta Basin and Kyune, Utah, where it would meet Union Pacific’s national railway system. This connection would allow oil trains to transport Uinta Basin crude through Colorado, and alongside the Colorado River for hundreds of miles, as they make their way south and east to refineries in Texas and Louisiana.

With the railway in place, the Uinta Basin’s oil industry could potentially quadruple its current output, adding up to 350,000 barrels per day in new crude oil extraction. For comparison, the Willow drilling project on Alaska’s North Slope—the one that sparked international outrage (and ongoing legal challenges) when the Biden administration approved it earlier this year—would produce 180,000 oil barrels per day at its peak. In the end, the Uinta Basin Railway could unleash a whopping 53 million metric tons (or 58.5 million tons) of carbon pollution into the atmosphere each year.

The proposed Uinta Basin Railway would allow two-mile-long oil trains to travel alongside the Colorado River, putting the waterway at risk.

Prisma by Dukas Presse-Agentur GmbH/Alamy

Oil trains: a disaster waiting to happen

The UBR would send up to 10 trains along the Colorado River every day, each stretching 2 miles long and carrying 100 tanker cars of heated crude through narrow canyons and along steep mountainsides. Even the STB’s substandard environmental impact statement (EIS) acknowledged that such an increase in rail traffic could bring a derailment every single year. With so many depending on a river that’s already struggling under the weight of prolonged drought and regular overdraws, an oil disaster on the Colorado River is simply not a risk worth taking.

It cannot be overstated how important the Colorado River is to this corner of the country. In an increasingly parched West, the river provides drinking water to 40 million people, from Wyoming to Mexico. The waterway also supports $15 billion in U.S. agriculture and $150 million in hydropower, and more than two dozen tribes rely on the Colorado to sustain their ways of life.

“A spill from a massive oil train would affect everything downstream and have catastrophic, lingering effects,” says Hattie Johnson of American Whitewater, a nonprofit working to protect rivers and the recreation industries they support. “It's a beautiful, remote section of river that provides an incredible experience, so just the impact of the train traffic itself would be concerning,” she says, adding that, in 2022, the stretch of river the trains would imperil generated $36 million through commercial rafting alone.

Port Arthur, Texas, home to a dense concentration of oil refineries, is one of the country's most polluted regions.

LM Otero/AP Photo

Communities at the end of the line

Via the railway, at least 85 percent of Uinta Basin crude oil would be headed for the Gulf Coast, an all-too-popular destination for the fossil fuel industry and other big polluters. Low-income areas and communities of color—such as those within Louisiana’s “Cancer Alley” and Port Arthur, Texas, home to one of the world’s largest oil refinery complexes—have been grappling with astronomically high levels of air pollution for decades. Pointing out the disproportionate and cumulative health and economic burdens they already shoulder, residents have urged the Biden administration to reject the railway.

“Enough is enough. We refuse to be sacrificed any further,” says John Beard Jr., executive director of the Port Arthur Community Action Network, a local environmental justice group. Beard, a former refinery worker, says that his community will no longer trade its health and its children’s future so that companies can make billions in profit. “We don’t want it. We don’t need it,” he says of the Utah crude. “We're going to keep fighting tooth and nail to prevent this from happening. We’re going to fight until we win.”

The proposed Uinta Basin Railway would cut through a roadless area in the Ashley National Forest.

Getty

Stopping the Uinta Basin expansion for good

While the denial of the STB’s permit dealt a blow to the railway’s timeline, environmentalists continue to mobilize against the Uinta Basin’s expansion on other fronts. For one, they’re urging the U.S. Forest Service to change its mind on allowing the railway to cut through a federally protected roadless area in Ashley National Forest. Roadless areas remain roadless for a reason. According to the Roadless Rule, these public forestlands “possess social and ecological values and characteristics that are becoming scarce in our nation’s increasingly developed landscape.” Such values include sources of freshwater, vital habitat for rare plant and animal species, and significant recreational, research, and educational opportunities. The Forest Service’s 2022 decision to allow the project that would involve building five bridges and blast three large tunnels in a roadless area was based on the very same EIS that a federal court deemed inadequate.

“The Forest Service could kill this by just saying we're not going to give you a right of way,” says Ted Zukoski, a senior attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity (CBD), the environmental group leading the lawsuit against the railway. “Now is the time for the Biden administration to live up to its words and make sure that this project can't go forward. Now is the chance for them to get it right.”

Yet, even if the Uinta Basin Railway finally hits a dead end, Utah’s oil drillers are already planning a partial workaround. This comes in the form of a separate proposal to truck more crude out of the Uinta Basin through the Wildcat Loadout facility, an oil train terminal near Price, Utah, that also connects with the national rail network. Right now, about 100 tanker trucks head down U.S. 191 each day from the Uinta Basin to Wildcat. The trucks drive through the arid mountainscape carrying 30,000 barrels of oil, but under the new plan—which would increase the terminal’s storage and loading capacity—there’d be another 260 of them hauling 100,000 barrels per day. The result would be one oil-filled tanker truck passing by every four minutes, all day, every day.

Since the Wildcat facility is located on federal land, the decision of whether it can expand its operations lies in the hands of the Bureau of Land Management. So environmental groups, including the CBD and NRDC, are urging the agency to conduct a comprehensive environmental review through a robust EIS. As of now, the ultimate fates of both the railway and the trucking proposal remain unknown, but one thing is certain: The pro-drilling set is determined to get more oil out of Utah.

“We'll continue to respond to ever-changing proposals that'll come up,” says Johnson. “We’re by no means done. There’s plenty of work to do.”

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

LNG is a dangerous substance that can lead to fires so hot they burn people up to a mile away.

Tell the Department of Transportation to ban bomb trains with no exceptions!

Five Ways the GOP-Led Congress Plans to Attack the Environment

How to Become a Community Scientist

The Clean Air Act 101