Water Is Life—from Standing Rock to Oaxaca’s Mixtecan Highlands

A geographer sees a familiar pattern of government-backed energy projects devastating Indigenous communities and violating tribal sovereignty.

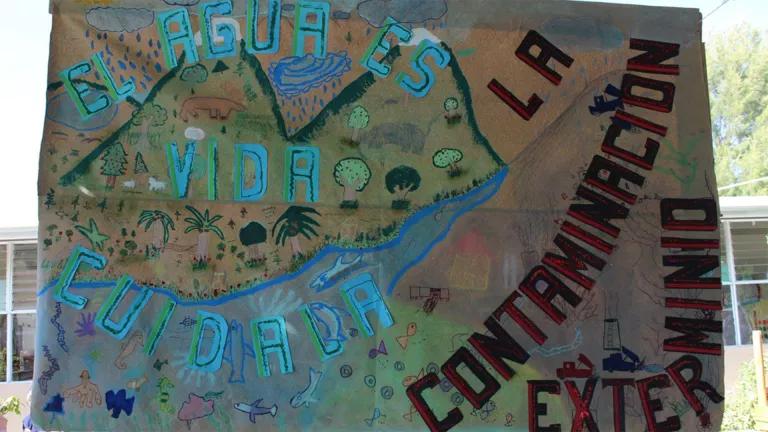

At the entrance of a 2018 science fair in my home state of Oaxaca in southern Mexico, a banner made of brown butcher paper swayed above me. With markers and crayons, the primary school students had depicted two worlds colliding: one, a lush mountain and a river teeming with plants and animals; the other, a barren landscape scarred and contaminated by industry. The poster offered a remedy, the extermination of pollution, along with a simple statement: El agua es vida.

Water is life.

I had heard this before. I stood and stared, immobile, mapping connections in my mind. I descend from the Ñuu Savi, which means “people of rain” in the Indigenous Mixtecan language. As a critical geographer in training, I’ve been studying how power dynamics intersect with the human and nonhuman forces that have shaped our environmental landscapes throughout time. And I’ve grown familiar with a pattern of threats to water resources and tribal sovereignty occurring across many Indigenous lands, including my own.

Agua es vida, water is life, and in Lakota—one of two dialects spoken by the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe of South Dakota—mni wiconi. Since 2016, the tribe has been fighting to protect its main water source from the Dakota Access Pipeline (DAPL). The pipeline has been shuttling around 500,000 barrels of Bakken crude oil beneath the Missouri River at Lake Oahe daily since 2017, and despite the abysmal safety record of its owner, Energy Transfer LP, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (the Corps) has so far allowed the pipeline’s operation to continue. Most recently, in a draft environmental impact statement, the Corps listed a number of possible outcomes for the pipeline, but most of them would basically permit business-as-usual operations for the oil and gas industry.

When the management of lakes, rivers, and dams is taken out of the hands of a land’s original caretakers, it is an immense environmental injustice. More than 2,000 miles stand between South Dakota and Oaxaca, but in both places, the Indigenous communities depend on important hydrological basins that are threatened by ill-conceived developmental projects. Mni wiconi is the plea that binds us together. So I dove deeper into the #NoDAPL case to understand the parallels we face.

A poster reading Agua es Vida—water is life—hangs at the entrance of a 2018 primary school science fair in Oaxaca, Mexico. The banner depicts a lush mountain and a river with plants and animals opposite a barren landscape scarred by industry.

Courtesy of Elybeth Alcantar, 2018

El agua es vida

Similar to the Corps’s dam projects on the Missouri River that created Lake Oahe in the last century, dam construction in Mexico also led to the displacement of huge numbers of people, most of them Indigenous. By 2006, those displaced by large dams in my home country reached a staggering 185,000 people.

Very few rivers and tributaries run through the arid Mixtecan highlands of northwestern Oaxaca, and yet there are still government-backed hydroelectric projects, like the Tamazulapam Dam, and reservoirs attempting to control the natural flows. Operating under permits from the Mexican Energy Regulatory Commission, some projects forced the relocations of Indigenous communities and disrupted the rivers and ecosystems they depend upon. These are just some of the environmental injustices at play in Oaxaca, where at least 66 sites have been identified for potential future hydroelectric projects. Since 2007, a fight against a dam slated for the Verde River has galvanized several Indigenous and Afro-Mexican communities on the state’s Pacific Coast. Tragically, in recent years, six of the anti-dam activists here have been murdered.

When the safety of a water source is compromised, the health of everything that relies on that water is as well. In addition to concerns about drinking water and irrigation for crops, a DAPL oil disaster would threaten the ecosystems within and along the Missouri River and its tributaries, which support endangered species, such as the pallid sturgeon, northern long-eared bat, scaleshell mussel, and piping plover. And while 51 of the 67 fish species that swim these rivers are rare or on the decline, several others provide food and livelihoods for the tribe, as does a nearby pasture for the Standing Rock bison program.

After an interview with AFP explaining his tribe's opposition to the Dakota Access Pipeline, Ron His Horse Is Thunder, a spokesman for the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, walks along a bank of the Cannonball River, which connects with the Missouri River and is the source of the tribe's drinking water, on September 4, 2016.

Robyn Beck/AFP/Getty Images

La contaminación exterminio

There’s little reason to wonder why the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration (PHMSA) considers the site of the pipeline’s crossing at the Cannonball River, and the two miles downriver, a High Consequence Area (HCA). For hazardous liquid pipelines, PHMSA defines HCAs as populated areas, drinking water sources, and places with unusually sensitive ecological resources. In a letter to the Corps in May, Janet Alkire, chairwoman of the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe, detailed why Energy Transfer cannot be trusted with keeping such areas safe. Between 2016 and 2020, she wrote, pipelines owned by Energy Transfer (which span the country and total nearly 125,000 miles) spilled more than a million gallons of oil. During this time, 21 of the company’s oil spills happened within HCAs.

The tribe’s water rights—as provided by the Fort Laramie treaties of 1851 and 1868—cover the Missouri River Basin’s tributaries and groundwater. Should the DAPL rupture, the tribe would be a first responder. Yet so far, the Corps has failed to provide adequate data, including worst-case scenario reports, to the tribe and other frontline communities. Such a lack of transparency hamstrings the tribe’s emergency response plans, putting the local ecosystem and water supply at increased risk. Without this information, the tribe cannot properly prepare for and make quick, sound decisions in the event of an oil disaster. Making matters even more precarious, the Corps has been keeping water levels in Lake Oahe too low for boats to access the pipeline’s shutoff valves in the case of an emergency.

“The Corps of Engineers has drained the Oahe reservoir,” writes Alkire, “causing our drinking water system to impose shortages, damaging our irrigation intakes, destroying fish and wildlife habitat, damaging the homes and properties of tribal members, and rendering oil cleanup to be virtually impossible, if there were to be an oil spill today.”

For Indigenous Peoples across North America (and beyond), our input, our demands, and our cries of “water is life” have been ignored. How can we be respected as sovereign nations when the rivers that run through our traditional homelands and territories are managed solely by federal agencies? True transparency would see Indigenous communities at the forefront of any environmental reviews, assessments, and decisions concerning the resources within their territories. True environmental justice would never deem our lands, health, and lives expendable in the first place.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

The Unlikely Takedown of Keystone XL

10 Threats from the Canadian Tar Sands Industry

When You Poison Our Lands, You Poison Us