News from Montreal Protocol: Our Ozone & Climate Guardian

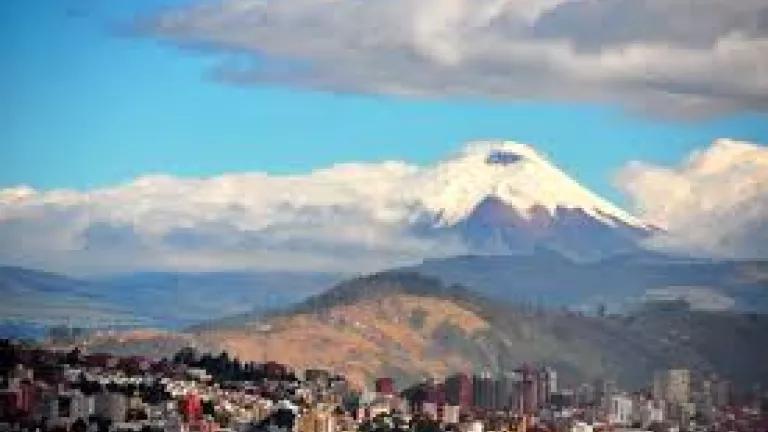

The splendid vistas, high altitude, and thin air of Quito, Ecuador, were a fitting venue for the annual meeting of the world’s most successful treaty to protect our atmosphere, the Montreal Protocol.

Every country on earth belongs to the Montreal Protocol, the 30-year-old treaty that safeguards the ozone layer and curbs the most powerful climate-changing pollutants. In Quito, delegates from more than 100 parties heard from scientists that the ozone layer is beginning to recover. They considered countries’ progress—and problems—in phasing out chlorofluorocarbons (CFCs) and other ozone-depleting chemicals.

The parties also continued preparations to phase down another set of climate pollutants called hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) under the 2016 Kigali Amendment, which comes into force this January. They took an important step to emphasize energy efficiency in the HFC phase-down—potentially doubling the climate benefit of eliminating HFCs. And they put a potential new threat to the ozone layer—a form of geoengineering—on the treaty’s radar screen.

Ozone Layer on the Mend, Less Warming too.

The world’s top atmospheric scientists reported that the stratospheric ozone layer, which shields the earth’s surface from dangerous ultraviolet radiation, is recovering from the grievous harm done by ozone-depleting chemicals. The 2018 Scientific Assessment of Ozone Depletion finds that with the phase out of those chemicals the Antarctic ozone hole is recovering and is on track to close in the 2060s. Ozone levels over heavily populated mid-latitude regions of the northern hemisphere will return to 1980 levels by the 2030s, and by the 2050s over the same latitudes in the southern hemisphere.

Eliminating CFCs and other ozone depleters has also reduced the threat of climate change, because these chemicals double as powerful heat-trapping pollutants.

This is the finest legacy of the Montreal Protocol. In the 1970s, scientists discovered that CFCs and related chemicals—emitted from aerosol cans, refrigeration and air-conditioning systems, insulating foams, solvent cleaning, and fire-protection systems—were destroying the ozone layer. The Montreal Protocol, agreed in 1987, phased out the production and use of the worst of these chemicals worldwide by 2010, and other ozone-depleting substances are on track for phase-out by 2030.

Threat from Illegal CFCs

But alongside the good news, scientists presented further evidence of illegal production of CFC-11 in eastern Asia. All global production of CFC-11 was banned under the Protocol by 2010. But the Scientific Assessment confirms findings earlier this year by scientists with the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA). Despite the ban, it is estimated that some 10,000 tons of newly manufactured CFC-11 are being released each year from that region.

These excess emissions were originally detected in plumes of air emanating from east Asia by monitors at the Mauna Loa observatory in Hawaii. Monitoring sites in Japan and South Korea have now corroborate the findings. There are also signs of excess emissions of carbon tetrachloride, another ozone-depleter from which CFCs are made.

Scientists estimate that if these CFC-11 emissions were to continue indefinitely, they would delay the ozone layer’s recovery by seven years over mid-latitude population centers, and by 20 years over Antarctica, resulting in millions of additional skin cancers, cataracts, and more.

China remains in the spotlight as the most likely source of these emissions. The Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA) reported findings (here and here) of illicit CFC-11 in Chinese-made insulating foams.

The Chinese delegation reported that authorities have stepped-up inspection and enforcement efforts, finding several factories illegally making foam insulation with CFC-11 and shuttering at least one illegal CFC-11 production plant. But the amount found at that site—about 30 tons—is far short of the estimated 10,000 tons of excess emissions each year.

China needs to continue and deepen its investigation and enforcement activities, and to share data more transparently. A start could be to publish atmospheric monitoring data from stations within China, which together with data from other monitoring stations could further pinpoint the location of emissions.

Urban scale monitoring could, like a chemical bloodhound, help authorities find facilities where CFC-11 insulation is being made and used, and that could lead them to illegal chemical production facilities. Additional air monitoring and enforcement efforts are also needed to find and shut down illegal production and use.

It’s to the credit of global atmospheric monitoring institutions that the excess CFC-11 emissions were detected. Now countries must use all of the Montreal treaty’s tools to respond. The parties adopted a decision setting multiple steps in motion, first by calling on the scientific and technical bodies of the Montreal Protocol to do more to pinpoint potential sources. The decision calls on all countries to share any data they have on CFC emissions and to contribute to the scientific and technological efforts to identify and neutralize the emissions sources.

The decision also reiterates the importance of each country continuing to meet its obligations to phase out CFCs under the Protocol and funding agreements, and presses each country to promptly and transparently report any noncompliance that might be contributing to the increase of CFC-11 emissions.

HFC Phase-Down Starts January 1.

The Kigali Amendment, the treaty’s landmark pact to phase down HFCs worldwide, will enter into force January 1, 2019. More than 60 countries have ratified the agreement, far more than the 20 needed for a timely start, and many more reported that they will join soon.

The United States said last year that it was considering ratification. Industry organizations continue to urge the Trump administration to send the Kigali Amendment to the Senate where genuinely bipartisan support exists for approving ratification.

HFCs are super pollutants that have thousands of times more heat-trapping power than carbon dioxide. The Scientific Assessment found that the phase-down could avoid 0.3-0.5 degrees C of further warming. This is an essential step in global efforts to hold overall warming to 1.5 degrees C, and avoid the catastrophic impacts that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change projects will accompany greater warming.

In Quito, the Montreal treaty parties took several steps to encourage greater energy efficiency while converting away from HFCs—steps that potentially could double the climate protection payoff of replacing the HFCs themselves by reducing power demand and the associated carbon dioxide emissions.

As one key step, the parties directed their funding arm (the Multilateral Fund (MLF)) to explore co-funding and other arrangements to promote energy efficiency with the Global Environment Facility, the World Bank, and other funding institutions. The parties also agreed to allow countries to use certain MLF funds to promote energy efficiency, for example by adopting minimum energy performance standards (MEPS), a crucial building block in national programs to reduce appliance energy use and decrease the need for harmful electricity generation.

Protecting the Ozone Layer from New Dangers

One idea for slowing global warming—called “solar radiation management”—involves injecting substances into the stratosphere to reflect some of the sun’s rays before they heat the lower atmosphere. But putting sulfates or other particles into the stratosphere could further deplete the ozone layer—a risk identified in the IPCC’s 1.5°C report.

Protecting the ozone layer even from well-intentioned schemes to combat warming is emphatically the province of the Montreal Protocol. So a group of countries proposed that the Protocol’s scientific assessment panel report on the potential impact of these solar radiation management techniques. Delegations will discuss next year how the Protocol, as the guardian of the stratosphere, should evaluate the risks these techniques pose, and determine whether such activities should be allowed.

Solid achievements. More to do.