New Data: Animal vs. Human Antibiotic Use Remains Lopsided

Our analysis shows 44% more medically important drugs are destined for cattle and swine than for human medical use.

By David Wallinga and Avinash Kar, NRDC, and Eili Klein, Center on Disease Dynamics, Economics & Policy

Tragically, our nation’s response to COVID-19 shows what happens when public health isn’t protected, science and scientists are not trusted, and the nation’s preparedness is not prioritized.

For decades, U.S. policymakers have been aware of the rising threat from infections caused by antibiotic resistant bacteria (aka superbugs). Superbugs already infect more than 2.8 million people each year in the United States, contributing to between 35,000 and 162,000 deaths.

And yet the same policymakers continue to fail to take meaningful action to protect the public (as noted in NRDC’s blog, To Protect the Future, Protect Antibiotics). In the absence of such action, the rates of illness and death could continue to rise, eventually generating economic impacts that on a global scale might look similar to what we now are seeing with COVID-19.

The antibiotic resistance crisis is driven in large part by ongoing antibiotic misuse and overuse. Unnecessary antibiotic use, whether in hospitals or pharmacies, on farms or feedlots, contributes to the proliferation and spread of resistant bacteria and genes. That’s why the tracking and reporting of antibiotic resistance and antibiotic use, wherever it occurs, is particularly important.

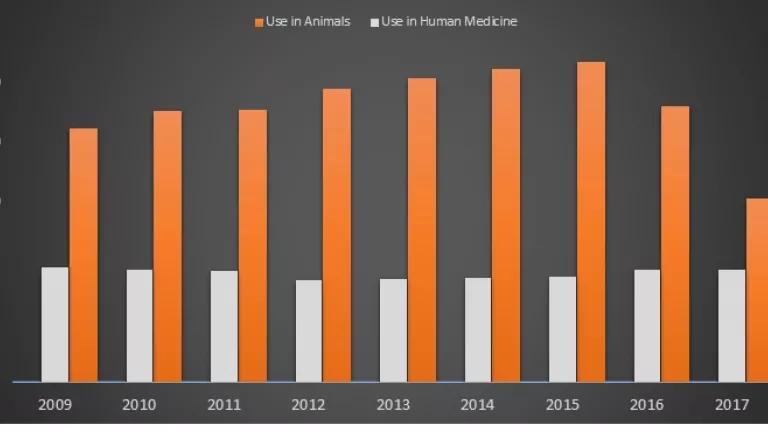

Figure 1 is a side-by-side comparison of antibiotics sold in the U.S. for human medicine, and for use in livestock and poultry production. It is a comparison that makes use of the latest (2017) data on human sales, which are not publicly available. Even taking into account a large decline from 2015 to 2017, antibiotic sales for use in food-producing animals continue to exceed sales of those same drugs for human medicine by a large margin.[1] Worryingly, those sales rose again in 2018, suggesting that previous declines may only have been temporary.

This kind of side-by-side comparison is essential information for a public whose future health depends on antibiotics remaining both available and effective. U.S. policymakers should act immediately to ensure these comparisons are made and publicly released each year. To more meaningfully address the antibiotic resistance crisis, other policy changes are also urgently needed. Later in the blog, we point out some of the critical steps that policymakers must take.

Figure 1. Antibiotic Sales for Use in Human Medicine vs. Food Animal Production

Moving Beyond Secrecy

Countries that have greatly reduced antibiotic use, particularly in livestock production, typically are the ones that have comprehensively tracked antibiotic use and resistance, and have issued regular reports integrating that information across human and animal settings. That does not describe the United States.

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) is now producing annual reports on how antibiotics are being prescribed in human medicine, down to the state and county level. National data on the sales of medical antibiotics are still not reported, however. The human sales information used to create Figure 1 were obtained from IQVIA by the Center for Disease Dynamics, Economics and Policy (CDDEP), which purchased those data.

The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) started releasing national data on farm sales of medically important antibiotics in December 2010, but only after Congress specifically directed it to do so. It was not until 2016 that the FDA began requiring pharmaceutical companies to report their national sales data broken out by major food-producing species (cattle, swine, chickens and turkeys). Unlike CDC's practice, the FDA does not break down sales data to the state or local level. Nor does the FDA collect data on actual antibiotic use at the farm level.

Federal policymakers have failed to heed repeated calls to take action to ensure that comprehensive data on the actual use of medically important antibiotics are collected at the farm level, and regularly reported on. The lack of detailed antibiotics information is part of a pattern of secrecy that we have noted previously around livestock practices, but especially around antibiotic use.

Comparable and integrated analyses covering both sales and use of medically important antibiotics are urgently needed. Such analyses are essential for both policymakers and the public to understand more precisely how these precious medicines are being used on farms and feedlots, and whether U.S. efforts to curb unnecessary use is succeeding or falling short. Unlike Canada, the United Kingdom, Denmark or the Netherlands, the U.S. government also does not release annual reports that integrate the human and animal sides of the antibiotic resistance problem.

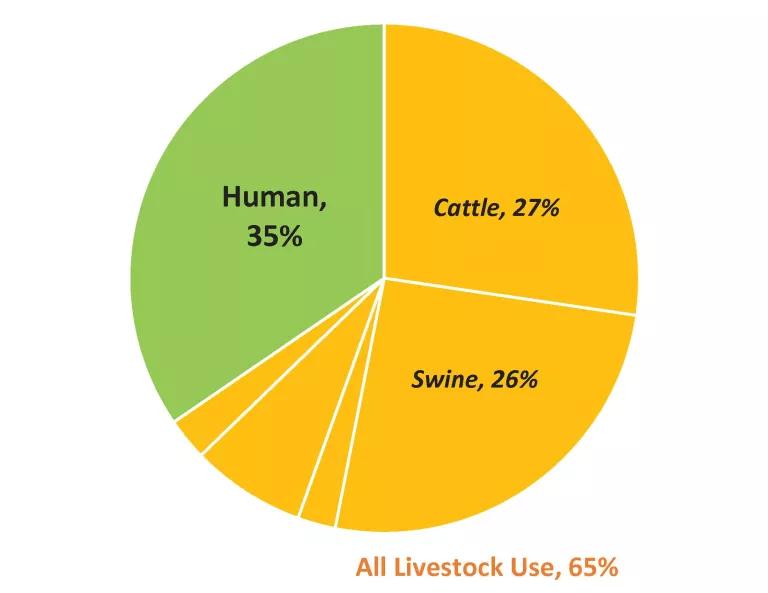

The data in Table 1, along with Figure 2, show that while roughly 65 percent of medically important antibiotics currently sold in the U.S. are for food animal production, cattle and swine production together consume about 44% more of these drugs than does human medicine (10.8 million pounds vs 7.5 million pounds of antibiotic active ingredient).

Most of the time, these antibiotics are fed to herds (or flocks) of cattle, pigs, turkeys or other animals whether or not they are sick, to compensate for risks created by the industrial conditions under which those animals raised. As previously noted, this very problematic practice fuels the proliferation and spread of antibiotic resistance.

What’s Needed

As a matter of both policy and practice, more needs to be done to reduce unnecessary antibiotic use. Many experts believe that antibiotic resistance overall cannot be tackled effectively or successfully without addressing antibiotic misuse and overuse on U.S. farms and feedlots.

Despite years of warning, two-thirds of all medically important antibiotics continue to be sold for use in livestock production, not for treating sick people—and many if not most of the animal uses are unnecessary. It’s urgent that the leadership of U.S. federal agencies, as well as in Congress, work harder to protect our future by protecting our antibiotics. Providing the public each year with side-by-side comparisons of the use of these precious medicines in human medicine and in food-producing animals, is an important step. Additional essential steps include the following:

- Ensuring that livestock producers are required to report annually on their on-farm use of antibiotics.

- Making critical investments to create a national system that collects, integrates, and publishes annual data on antibiotic use and antibiotic resistance, both in human and animal settings.

- Setting national targets for reducing medically important antibiotic use, especially in specific livestock sectors such as the beef and pork industries where most such antibiotics are now used.

Figure 2. Medically Important Antibiotics Sold (U.S.) for Cattle Production, Other Livestock Production and Human Medicine

[1] To be clear, the latest available human data are from 2017 while FDA data on animal use are from 2018. Absent any abrupt changes to medical practice or the U.S. population from 2017 to 2018, however, it seems reasonable to assume that 2018 sales for human medicine will not vary much from 2017 (as reflected in Fig.1), given that human use numbers have been relatively consistent for the previous 8 years.