Green Procurement Programs for Steel Cannot Merely Lock in the Status Quo

Low-carbon procurement programs must encourage decarbonization across the steel industry.

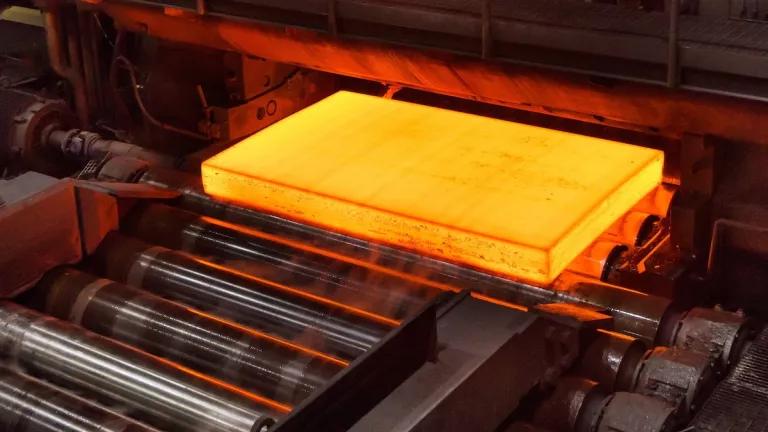

The Essar Steel plant on St. Mary's River in Sault Sainte Marie, Michigan

Steel is the most used metal on earth, but it presents a climate dilemma. While steel will be necessary to build clean technologies like wind turbines and electric vehicles, production of steel is a significant contributor to climate change. Many steel products today consist of a blend of carbon-intensive primary steel, made from iron ore using fossil fuels, and lower-carbon secondary steel, made from scrap metal using electricity. Both steel production pathways are necessary and therefore need to decarbonize.

Fortunately, the U.S. government is taking action to encourage decarbonization of steel production through game-changing investments made by the Inflation Reduction Act (IRA) and Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. These investments include billions of dollars to support Buy Clean programs, which were created to provide an incentive for the federal procurement of low-carbon materials, including steel.

As the federal government works to implement these new low-carbon procurement programs, they must create a real incentive to reduce emissions across the industry. For steel, this means that low-carbon procurement programs must be structured to take into consideration the vastly different carbon intensity between the two dominant steel production pathways (primary steel produced mainly from iron ore and secondary steel produced mainly from recycling steel scrap) and encourage both to reduce emissions. In addition, federal agencies, like the U.S. Department of Transportation (DOT) and U.S. General Services Administration (GSA), should pilot novel procurement policy designs like advanced purchase commitments for ultra-low-carbon steel.

To get low-carbon procurement right, we’ll need to put to work the enormous purchasing power of the federal government to help drive down industrial emissions. We must avoid poor policy design choices that would merely reshuffle the deck with lower-carbon products flowing to federal buyers, higher-carbon goods staying on the private market, and the overall carbon intensity of the domestic steel industry staying the same.

Steel production today

Currently, steel is produced through two main pathways with dramatically different climate impacts (previously described in detail here). In primary steelmaking, iron ore is processed using an integrated blast furnace/basic oxygen furnace system, which can be very carbon-intensive, or in a direct-reduced iron plant. In secondary steelmaking, an electric arc furnace (EAF) is used to melt existing steel (primarily scrap) and recycle it into a new steel product, which uses less energy per ton of steel and results in substantially fewer emissions compared to the dominant primary steel production method. Because of a limited supply of scrap steel and because EAF steelmaking requires non-scrap inputs, both production methods will be necessary to meet total steel demand for the foreseeable future.

Here’s how Buy Clean programs can be most effective in driving down emissions

Buy Clean programs create an incentive for industrial decarbonization by creating demand for lower-carbon materials that may not currently be cost-competitive. As the single-largest purchaser of common building materials like steel, the federal government is uniquely positioned to drive change in the market.

With new funding authority under the IRA, agencies are already working to support Buy Clean on a federal level. The IRA includes support for Buy Clean enabling mechanisms, like $250 million for grants and technical assistance that will help manufacturers produce environmental product declarations. The law invests more than $5 billion for Buy Clean pilot programs at DOT and GSA, among others.

If these Buy Clean procurement programs are to be effective in driving down steel sector emissions, they must be designed to encourage decarbonization of both steel production pathways. To do this, agencies should initially, and over the medium term, implement a bifurcated standard for steel—a different threshold for steel that’s produced using an EAF and steel that’s produced at an integrated mill—or a standard that takes into account the percentage of primary and secondary steel in a final product.

A bifurcated standard will make Buy Clean work by recognizing the inherent differences between the different methods of steel production and ensuring competition among comparable facilities. Under IRA-funded Buy Clean pilot programs, agencies must create a preference for materials with “substantially lower levels of embodied greenhouse gas emissions…compared to estimated industry averages of similar materials or products,” as defined by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. For steel, without this initial bifurcation between primary and secondary steel, there is a risk that secondary steel producers will be able to secure federal contracts without taking action to reduce emissions because secondary steel is already produced with substantially lower emissions than an industry average that includes primary steel production. Given this secondary steel carbon advantage, primary steel producers may opt out of federal projects altogether. If that happens, the public resources invested in Buy Clean will have been wasted.

Looking forward, Buy Clean programs should encourage continued reduction in emissions and should take into consideration emerging technologies, like direct reduction of iron using green hydrogen and iron production through molten oxide electrolysis, both of which have the potential to significantly reduce or eliminate emissions from steel that is produced from raw iron ore. Over time, agencies should set increasingly stringent standards for what constitutes a low-carbon material under Buy Clean. Once emission intensities for steel production pathways start to converge, agencies should establish a single embodied emissions standard for all steel products purchased under Buy Clean.

Beyond Buy Clean

Buy Clean programs are a necessary step in leveraging the enormous purchasing power of the federal government to drive emissions reduction across the steel industry. Creatively designed procurement policies can support transformative change in the near term, and agencies should consider additional tools like Advanced Market Commitments (AMCs) that can create demand for nascent ultralow emissions products.

Buy Clean programs are limited to commercially available products. By contrast, AMCs can help jump-start emerging markets. AMCs are binding agreements to purchase a specified product at a preset price. They are often used to support the development of new or novel technologies by guaranteeing a market once the product is developed.

Toward this end, agencies should pilot AMCs for transformational, pre-commercial products that drive even deeper industrial emissions reductions, such as near-zero carbon steel. Manufacturers are often reluctant to make substantial investments in decarbonizing their operations without a clear financial upside. AMCs can provide certainty to steel producers by ensuring that if a near-zero carbon steel line is produced, it will have an initial market.

By implementing carefully created procurement programs, federal policy makers can help spur industrial decarbonization while supporting good, domestic jobs.