Electric Vehicle Basics

Curious about how an electric vehicle works and whether it's actually better for the environment? Spoiler: it is. Allow us to explain.

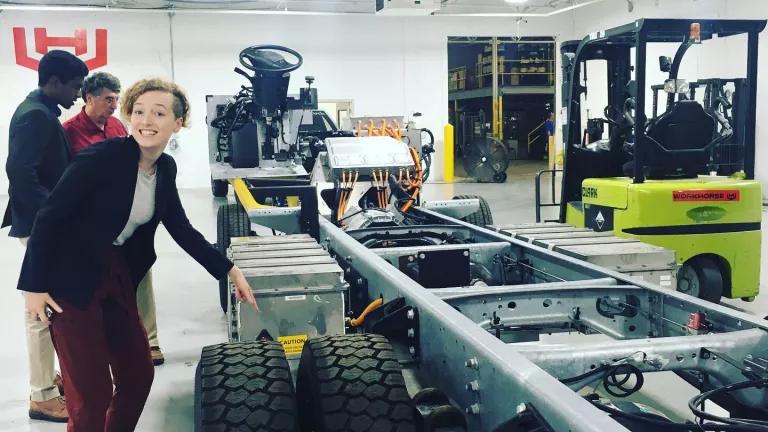

The drivetrain or "skateboard" from an older iteration of Workhorse's medium-duty electric truck

This is the ninth blog in a series about our Midwest electric vehicle adventure.

Going into our electric road trip through the Midwest, we were well aware of numerous benefits that electric vehicles (EVs) could provide: they are only getting increasingly better for the environment than their gas-guzzling counterparts, the growing industry supports many kinds of new jobs, and the lack of tailpipe emissions can provide substantial health benefits in our most vulnerable communities. After ten days behind the wheel and numerous conversations with EV owners, advocates, and manufacturers, we came away from the trip overwhelmed with the countless additional perks and benefits of driving an EV. Allow us to explain:

What are electric vehicles? Efficient, for one

Before we dive deeper here, what exactly is an electric vehicle and how does it work? An electric vehicle is a car powered by electricity—and this category is broader than you may think. It includes plug-in hybrid, hybrid, and fuel cell electric vehicles, but this blog is going to focus specifically on battery electric vehicles, sometimes called BEVs. In these EVs, there are no tailpipe emissions, as electricity from the battery powers an electric motor which then turns the wheels and sends your car forward.

Just like energy efficiency has driven down emissions in the power sector, efficiency is also a primary driver of cleaning up the transportation sector. Electric motors makes vehicles substantially more efficient than internal combustion engines (ICEs). Electric motors convert over 85 percent of electrical energy into mechanical energy, or motion, compared to less than 40 percent for a gas combustion engine. These efficiencies are even lower after considering losses as heat in the drivetrain, which is the collection of components that translate the power created in an electric motor or combustion engine to the wheels. According to the Department of Energy (DOE), in an EV, about 59-62 percent of the electrical energy from the grid goes to turning the wheels, whereas gas combustion vehicles only convert about 17-21 percent of energy from burning fuel into moving the car. This means that an electric vehicle is roughly three times as efficient as an ICE vehicle. Needing less energy to power your car also helps bring down the cost.

Electric vehicles are clean, and only getting cleaner

When it comes to air quality and climate change, electric vehicles are an especially effective tool for decarbonization, and minimizing soot and smog, because their emissions are linked to the power sector—as the grid continues to get cleaner, so does your vehicle. Critics have falsely questioned whether EVs are truly cleaner today, but modeling from EPRI-NRDC and life-cycle analysis from the Union of Concerned Scientists (UCS) definitively demonstrate that they already are. On average, an EV emits about half as much carbon dioxide as a gas-burning vehicle. For EVs, this includes not only the emissions from the power plant where the electricity powering the EV is produced, but also the emissions associated with manufacturing the battery itself. The UCS analysis shows that even EVs powered by a coal-dominated grid are still cleaner than their ICE counterparts. The grid can and must continue to add clean, renewable energy sources, like wind and solar. As it does, we would do well by the planet, children, the elderly, and people with pre-existing respiratory conditions by simultaneously cleaning up the transportation sector and encouraging widespread EV adoption.

It’s more fun to drive an EV

Don’t take it from me. Take it from Chris, a professional race car driver who we met just outside of Chicago. She knows everything there is to know about cars, and she and her husband decided to buy a Chevrolet Spark EV because no other car on the market provided as much of a thrill. Or take it from Jane, a three-time EV owner with a self-professed need for speed who we met outside of Indianapolis.

So what makes EVs the preferred choice for car enthusiasts? In a word, torque. In an EV, instant torque is generated by an electric current and magnetic fields in the electric motor, whereas a gas engine takes much longer to combust gas and turn the crankshaft. This instant torque in an EV is what throws you back against the seat when you accelerate from a stoplight, leaving everyone else in the dust. Just how good is the torque in an EV? Well, you can buy a used Chevy Spark EV for less than $10,000, and it will give you more torque than a Ferrari. Not a bad deal if you ask me.

EVs also typically have a low center of mass and evenly distributed weight due to their “skateboard.” This is EV manufacturers’ preferred term for the chassis, or the base frame of a vehicle, which includes a battery pack spread across the bottom. The battery pack is one of the heaviest components of an EV, which replaces the bulky gas engine with a lighter electric motor. Having all that weight near the ground helps the car stick to the road and expertly maneuver through twists and turns.

Life is easier with an EV

While opponents often frame the need to charge an electric car as a disadvantage and the resulting change in behavior as a barrier to EV adoption, owning an EV actually stands to be even more convenient for drivers.

Today, approximately 80 percent of EV charging occurs at home because of the convenience and lower costs compared to most public charging—to say nothing of gas prices, which already make EVs the most financially savvy option for some. As EV ranges continue to increase, even long-distance drivers like us will need to make fewer pit stops to make sure their cars have enough juice to get to their destination. For drivers that switch from a gas-burning vehicle to an EV, that’s one less to-do as they leave the gas station behind forever.

But going to the gas station isn’t the only maintenance needed for most cars on the road today: There are routine visits to the mechanic to replace fluids and a variety of moving parts. If you dread these trips as much as we do, have you considered switching to an electric vehicle? In an EV, there is no internal combustion engine, fuel tank, or fuel pumps. You won’t need to go get an oil change, and due to the use of regenerative braking, you won’t need to get your brakes changed as often either. Many EVs don’t even need or have a transmission. Those that do have a much simpler, single-speed system as opposed to the multi-speed gearboxes in gas-burning vehicles.

In fact, according to Tesla, their drivetrain only has about 17 moving parts compared to the 200 or so in a typical drivetrain for an internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicle. The difference is even starker when considering the complexity of the piece that powers the car: an ICE engine has hundreds of moving parts whereas an electric motor typically has just 2. With increased complexity comes increased costs—not just up front, but also over and over again when you need to spend money to maintain the complex machines that ICE cars are. An EV can save you money short term on fuel, while making life even more convenient over the long term on maintenance.

EVs are sneaky

When we first turned on our Chevy Bolt, we immediately noticed just how silent it is. Admittedly, it can be a little unnerving at first—we weren’t even sure if it was on! But this anxiety soon evolved into excitement, as we could easily listen to music or actually have a conversation while driving without having to shout.

And the benefits of silent transportation extend far beyond passenger convenience. Noise pollution from vehicles, including buses, in urban neighborhoods isn’t just a nuisance, it’s a contributor to a wide array of health conditions. As the trend towards urbanization continues, it is increasingly important that we effectively address noise pollution. The electrification of cars, buses, trucks, and other noisy vehicles can help reduce pollution of many types and help us all sleep better at night.

EV technology continues to improve

A legitimate criticism of electric vehicles is that their range may decrease substantially in extremely cold weather. This was a concern that we heard repeatedly during our trip in the Midwest, with electric buses in cities like Indianapolis experiencing reductions in range of over 40 percent compared to the quoted range at 0 degrees Fahrenheit. In this case, the bus manufacturer has agreed to supply wireless charging infrastructure to Indianapolis to ensure that the buses can complete their routes even in the coldest of winter days, but this issue can be remedied by new battery chemistries that are not as sensitive to the cold, or simply by batteries with longer ranges.

This is how our Bolt showed us how much battery charge we had remaining, as well as internal and external temperatures. As you can see, the weather that day didn’t require much cooling, so most of our battery power was applied to driving the car.

Research suggests that a principle reason for range reduction in the cold is actually the use of space heating in the vehicle. Earlier this year, AAA released a study that showed a 12 percent reduction in range in the cold (20 degrees Fahrenheit) with no HVAC enabled, but, after the heater was turned on, the range dropped by 41 percent. This suggests that there is a lot of room for improvement in making vehicle heating more efficient. In fact, several automobile manufacturers are already working towards innovative solutions. Many EVs, including our Chevy Bolt, include heated steering wheels and heated seats in their cars. It turns out this is actually a much more efficient way to warm passengers up than to blow hot air into the space around them. After getting caught outside in the rain during a Midwest thunderstorm, we tried out these heating features and discovered we actually prefer them.

Other manufacturers, including Nissan, have replaced the electric resistance heating component with a much more efficient heat pump. This design leverages the same equipment used for air conditioning in the car to heat it as well, and the process has been found to reduce the energy needed to make the car comfortable for passengers by 50 percent. As less energy from the battery is needed to heat and cool the passenger, more of it can be used to get them where they need to go.

You should really try one out

After 10 days in our EV, we were not only impressed by the driving experience and all the EV champions we met along the way, but also by the curiosity and interest that folks had about our car and our road trip. Strangers would come up to us while we were charging and ask us questions about what we were driving, how far it could go, or how long it would take to charge. In these early days of electric vehicle deployment, everyone is understandably filled with thousands of questions, from how they work to how can they get one? EVs are new. They’re cool. They’re mysteriously silent. It’s important that EV manufacturers, dealerships, city policymakers, and, yes, EV drivers answer these questions and help bring more people into the fold. Once you sit behind the wheel, the only question you’ll have is, when can I do this again?

We went on a Midwest electric vehicle road trip to talk about transportation policy, highlight the already booming benefits of electric vehicles to local economies, and shatter stereotypes about what it means to be an electric vehicle driver. We’re blogging about our findings, including tips for other aspiring roadtrippers and policy suggestions for further progress.

Other blogs related to our electric adventure include:

- Driving (on) Clean Energy: Touring the Midwest in an EV

- State of the States: EVs and EV Policy in the Midwest

- Road Trip Report: How Ohioans Buy EVs (It Should Be Easier)

- Avoiding Range Anxiety with an EV Road Trip Checklist

- Road Trip Report: Midwest Cities Move Multimodal

- Midwest Electric Vehicles in 5 Maps

- Electric Vehicle Charging Basics

- Road Trip Report: On Charging Champions and Public Policy