Compost, Rodents, and Bears—Oh My!

As officials in Asheville, NC worked to develop the city's food scraps drop-off pilot program, they needed to take bear-proofing into close consideration.

Alaskan brown bear and her three cubs

Arthur T. LaBar, licensed under CC BY-NC 2.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/2.0/

Today kicks off Fat Bear Week, which occurs this year from October 5 through October 11, and during which the public can vote, bracket-style, to crown the year’s fattest Katmai bear: “Some of the largest brown bears on Earth make their home at Brooks River in Katmai National Park, Alaska. Brown bears get fat to survive and Fat Bear Week is an annual tournament celebrating their success in preparation for winter hibernation.”

In Asheville, North Carolina, they also celebrate bears – but not when those bears are getting into municipal discards, which is a local concern. As Kiera Bulan, Sustainability Program Manager for the City of Asheville, explains, “There has been interest in Asheville for many years to elevate compost beyond the ongoing backyard composting – but we aren’t quite able to invest in curbside food scraps pickup, so we started by exploring the possibility of creating public food scraps drop-off sites. Everyone’s first question was what about bears, won’t it attract bears.” As Bulan and her team continued to develop their food scraps drop-off pilot program, they needed to take bear-proofing into close consideration.

Black Bear and Dumpster

Bears weren’t a new issue for Asheville in terms of discards. If food scraps aren’t in compost, they’re in trash, so the sanitation department had long been engaged in solving the bears-in-bins issue. The department created an opt-in pilot program for trash bins which are picked up curbside, in which residents could purchase their own bear-proof trash bins themselves. Supplies of those bins quickly ran out, and there is currently a waitlist for future purchases.

The experience of residents (and city government) with bears getting into garbage cans meant that folks were understandably wary about plans related to food scraps drop-off. Bulan and her team were motivated to ensure that the pilot was set up for success and anticipate (and prevent) any opportunities for pushback – so number one on their to-do list was to create a bear-proof system.

Launching the Food Scraps Drop-Off Pilot

Asheville had long been interested in expanding organics diversion. Asheville and Buncombe County, with Bulan as lead, had already partnered with NRDC’s food waste team as a member of the Southeast cohort of our Food Matters Regional Initiative, a two-year partnership to help municipalities work together and with NRDC to advance comprehensive food waste reduction strategies. The city already offered curbside yard waste pickup, and was already supporting backyard composting through information and trainings as well as free giveaways of kitchen totes and backyard bin construction kits. As noted earlier, the city wasn’t ready to add curbside food scraps pickup to its services, but wanted to provide options for people who aren’t able to or won’t compost at home, including renters and apartment dwellers. A community drop-off pilot was conceived as an intermediate solution between home composting and curbside food scraps pickup, and a way for the city and community members to partner on, as Bulan says, “a shared problem with a shared solution, government and residents both contributing.”

In identifying sites for the food scraps drop-off pilot, bears were obviously top of mind, but there were other concerns as well. The team needed to select sites at facilities run by the city or county, with space for the proposed drop-off site, and prioritizing sites that were accessible to the community. Initially, they launched two pilot sites: one at the landfill, where there was already an existing drop-off area accepting trash and recyclables, and one at Stephens-Lee Community Center, located downtown, with active community engagement. The county operates the landfill site, and Stephens-Lee is a city parks and recreation facility, which helped forge a city-county partnership model for the pilot.

At the landfill site, the bins are located in an existing building with other drop-off bins for trash and recycling, and they don’t experience much bear trouble. But the site is farther away from neighborhoods, and not as accessible to many residents. At Stephens-Lee, Bulan’s team partnered with the parks and recreation department to install a prefabricated 8’x10’ shed with a “bear proof handle” and padlock on the door. The shed holds several bins (currently seven) and is locked between uses.

Initially, the food scraps drop-offs were available only for city and county employees, so they could work out any kinks in the system. After that pre-launch stage, the sites were opened to the public. Users are required to fill out a survey with information including their zip code, whether they are first-time or experienced composters, and so forth. There is no cost to participate.

Challenges and Lessons Learned

Work with haulers in planning stage: At first, Bulan tried to find bins that were themselves bear-proof, similar to the sanitation department’s piloted bear-proof trash bins. But those bins weren’t compatible with the system used by the organics recycling hauler, which has their own bins, and brings empty bins to switch out for full ones during pickups. In order for the city to use new bins for the drop-offs, they would have had to purchase enough bins to overhaul the entire setup for the hauler, which wasn’t feasible. Further, there was a concern that latching and unlatching the bear-proof bins would put stress on the bins, and increase the chances of them being left open inadvertently. Instead, Bulan focused on a shed that would enclose the existing hauler-provided bins. Also, as Bulan reasoned, “If the pilot failed, there would be lots of other uses for a shed at a parks facility – less so for lots of bins.” The bear-proof shed enclosing multiple bins reduces complications for drop-off for user, pickup for hauler, and expense for city.

Formalize partnerships and who’s doing what: Even though the drop-off sites are located on both city and county sites, one goal is to institutionalize the city-county partnership, which means figuring out logistics such as how to split the cost between partners and how to handle maintenance. Also, who reports pounds of organics recycled through the program as their diversion – city or county? This should be clear to ensure there is no double-counting, particularly in reporting diversion data to the state. Additionally, the city has one website and the county has another, but the public shouldn’t have to figure out which site to refer to for information on the program – the content on both webpages and on public-facing signs needs to be consistent, there should be a single form for user registration, and the public should have a single point of contact if they have questions. These concerns also apply in a public/private partnership model (e.g., locating a drop-off site at a grocery store). Bulan notes, “No matter who your partner is, co-branding can be accomplished without compromising consistency.”

Plan communications strategy up front: Bulan notes the importance of investing time and resources both up front and along the way to develop a public communications strategy (in coordination with any partners). As Bulan says, “To have a successful program, we need to communicate about it, keep tweaking and improving our communications, be in regular and ongoing communication with existing users, and also ensure new users are fully oriented.” A particular challenge is that Asheville publishes one list of materials suitable for home composting, and a different list of materials accepted in the food scraps drop-off program; most home composting systems shouldn’t incorporate meat or dairy, for example, since home composting isn’t guaranteed to reach temperatures necessary to kill any pathogens, and since those materials attract pests (not limited to bears). Asheville’s solution to this challenge is to post clear information on its website, and they also provide stickers for households to post on kitchen totes (or wherever they like) with home composting and drop-off instructions side by side.

Asheville How to Compost Sticker

Pilot to test concepts: The pilot strategy helped ensure that the hauler and the users could work with the existing setup. Bulan said, “It turns out people are willing to drive food scraps around! We’re still working with only a small proportion of our overall population, but so far, we’ve been pleasantly surprised by the engagement.” Also, the bears haven’t gotten into the shed so far, so the bear-proofing is a success.

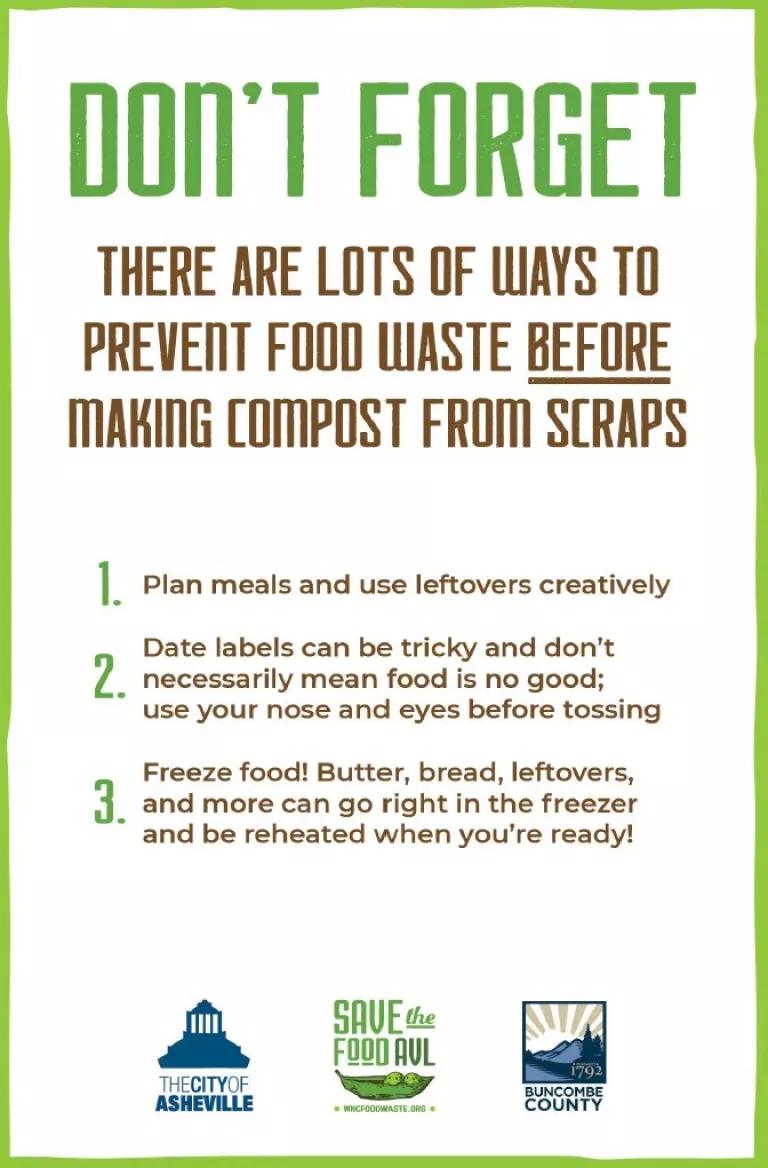

Incorporate food waste prevention messaging: As Bulan notes, “People love to talk about compost and it can distract from the conversation about going up the food recovery hierarchy.” NRDC’s research matches other studies in showing that composting makes people feel less guilty about wasting food – which means it’s very important to ensure that framing of media and outreach about the compost system include overall food waste reduction education, to emphasize that preventing food from going to waste in the first place and rescuing food for redistribution are more ecologically, economically, and socially preferable strategies than food scraps recycling (though of course recycling is better than disposal). On the other hand, Bulan observed that the media interest in the compost strategy provides a platform to discuss food waste prevention and food rescue.

Asheville Food Waste Prevention Tips

Impact to Date and Next Steps

Expansion: After establishing the initial drop-off sites at the landfill and Stephens-Lee, and opening those to the public, the team added two additional neighborhood sites, one at a recreation center (a city property) and one at a library (a county property). The team hopes to add more sites that are accessible to more neighborhoods and located at facilities or on routes where people already travel (such as recreation centers and libraries). The expansion strategy will incorporate data on where current users are already located (from zip code data provided at user registration), but also focus on where there may a need for more access to organics recycling (for example, neighborhoods with many multifamily residences). The team plans to use Asheville’s climate justice screening tool to determine which neighborhoods are historically under-resourced where hyperlocal sites might enable more users to participate through walking, biking, or taking transit to a drop-off site. They also plan to expand outreach through different methods (including neighborhood communications) to reach more people with information about the program.

Program data: In the past year or so since the initial pilot, over 1700 households in the city and county have signed up to participate in using the food scraps drop-off sites, and approximately 56 tons of organic waste have been diverted from the four existing sites (the last two sites added have only been open for three months or less). The majority of users noted in the survey that they had never composted before. Since the pilot launch, there have been at least ten earned media articles, news features, or blog posts on public-facing external sources related to the program.

Funding: The funding for the program to date has been through grants, including from NRDC as part of the Food Matters partnership, as well as a grant secured by Buncombe County from the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality, which funded the two existing expansion sites and will fund three additional sites. As part of further operationalizing the program, Bulan is hoping that it will be incorporated into the city and county budgets for upcoming years.

Learn more: To learn more about food waste reduction in Asheville and the surrounding region, check out the City of Asheville’s Food Waste Reduction Initiative webpage and the Western North Carolina Food Waste Solutions resources.

For those who are experiencing issues with critters slightly smaller than bears, an excellent guide was recently published by the Institute for Local Self-Reliance called “Oh, Rats! How to Avoid Rodents at Community Composting Sites.” The guide “is designed to support composters at community gardens, schools, urban farms, and other community venues in successfully managing their composting process to avoid rodents. Much of the information in the guide applies regardless of the composting system in place.”

ILSR "Oh, Rats!" Guide

And don’t forget to vote for your favorite fat bear before October 11!