US International Climate Finance Fails Again to Meet Moment

Congress and the Biden administration must put their money where their mouth is if they want the country to lead in addressing the climate crisis.

Congress unveiled a spending package for fiscal year 2023 that fails to deliver on the U.S.’s international climate finance commitments. This year’s bill includes slightly over $1 billion in direct climate finance—only $900,000 more than the previous year’s already woefully short amount. This will severely damage the U.S.’s ability to spur greater climate action from other major emitting countries, and continues to put the most vulnerable on the front lines of climate damage. Congress and the Biden administration must put their money where their mouth is if they want the U.S. to lead in addressing the climate crisis.

With this level of funding, it will be an extremely steep climb to meet President Biden’s climate finance pledge of $11.4 billion annually by next year. The State Department, US Agency for International Development (USAID), and the Treasury Department must urgently prioritize funding for climate across the entirety of the foreign assistance budget. Additionally, the Biden administration needs to light a fire under the Development Finance Corporation (DFC) and Export-Import Bank (Ex-Im) to mobilize additional finance, and also spearhead a wider effort to unleash tens of billions through reforming international financial institutions like the World Bank.

The White House and Congress’ failure to prioritize delivering much-needed investments in international climate action is a major setback. Below we assess the scale of the funding hole and the steps needed to begin filling it in the coming year.

FAILURE TO INVEST IN KEY STRATEGIES TO TACKLE THE CLIMATE CRISIS

The spending bill fails to drive investments in the key U.S. agencies and international funds needed to rapidly cut emissions this decade to hold global temperature increase to 1.5°C (2.7°F). It also does not provide sufficient support to the most vulnerable communities around the world who are already facing the disproportionate impacts of the climate crisis but have done the least to contribute to the problem. Climate change is a top-tier U.S. foreign policy priority and identified by the White House as “the greatest” national security threat facing all nations, but this spending bill falls woefully short of matching this rhetoric. The U.S. needs to invest reflecting that national security reality.

The below figure and sections provide a breakdown of Congressionally-directed appropriations of international climate finance.

Overall direct climate finance: at least $1.057 billion

This overall direct climate finance represents only a $900,000 increase from fiscal year 2022 (FY22), which itself was only a meager uptick from the international climate finance levels under President Trump. However, direct climate finance needed to increase by several billion to be on track to achieve President Biden’s commitment to deliver $11.4 billion in total international climate finance annually by next year.i Over 100 leading development, faith-based, environment and conservation, health, science, foreign policy, and business organizations called for Congress to dedicate no less than $3.76 billion in direct financing towards these programs. This Congressional appropriation must represent the floor, not the ceiling, of overall government spending on international climate action. The Biden administration will need to search under every couch cushion to find additional resources to dedicate to the crisis.

Bilateral climate programs: $715 million

The Department of State and U.S. Agency for International Development have been appropriated the same meager level of bilateral climate assistance as last fiscal year. President Biden requested $2.3 billion for these efforts, and the bill falling more than $1.5 billion short of that request. The bill requires no less than the following amounts be allocated for three bilateral programs:

- Adaptation: $270 million to support the most vulnerable countries in avoiding and minimizing the worst impacts of climate change.

- Clean energy: $260 million to help deliver the rapid renewable energy and energy efficiency deployment that developing countries need to leapfrog climate polluting technologies.

- Sustainable Landscapes: $185 million to spur reduction in deforestation, forest degradation, and unsustainable land-use practices in developing countries.

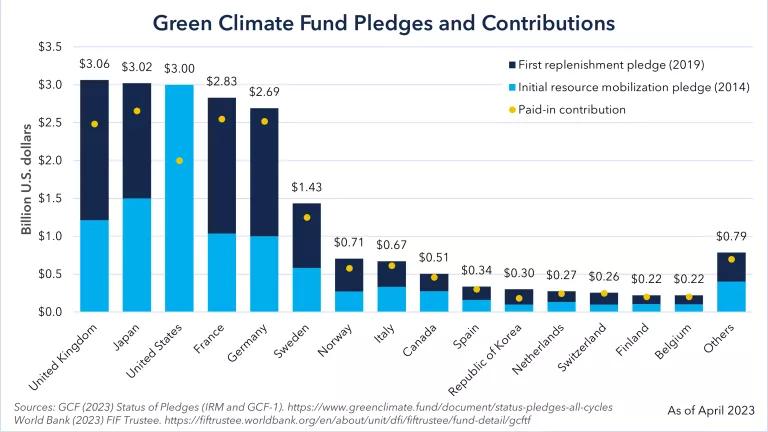

Green Climate Fund (GCF): $0 explicitly appropriated

Congress has again failed to provide a direct funding earmark for the GCF. However, the FY22 and FY23 spending bills do have flexibility for funding to be directed to the GCF to deliver on the U.S.’s 2014 pledge to contribute $3 billion to this fund – only $1 billion of which has been delivered to date. In 2019, other countries made another round of contributions, with most doubling their first commitments. There will be a new replenishment at the end of 2023. Before this, the U.S. must work to fully deliver its eight-year-old pledge to avoid being the only major country in arrears.

Clean Technology Fund: $125 million

These resources will go to the Accelerating the Coal Transition program which will help spur the renewable energy transition in key countries. Countries such as South Africa and Indonesia are using these resources to invest in their “Just Energy Transition Partnerships” (JETPs) to speed the early retirement of coal power plants, expand renewable energy, and support a just transition.

Global Environment Facility: $150.2 million

Supports developing countries to tackle a variety of pressing environmental challenges.

Other multilateral funds and agencies: $66.9 million

Additional multilateral funding is appropriated to: the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change and the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change ($15 million), the UN’s climate negotiating and science bodies, respectively; and the Montreal Protocol Multilateral Fund ($51.9 million), which provides assistance for developing countries to reduce super climate pollutants that are replacing ozone-depleting substances. The bill also allows the U.S. to continue contributing to the Adaptation Fund and Least Developed Countries Fund with funds from the adaptation bilateral account.

MISSED OPPORTUNITY TO MAKE TRANSFORMATIONAL INVESTMENTS

Robust and sustained investments are a lynchpin of America’s global climate leadership, and ability to rally the world to address the climate challenge. America’s actions are more important than its words—and money drives real action. This spending bill is another missed opportunity, on top of the woefully low amount that the White House and Congress dedicated last year (see figure below).

U.S. Appropriated International Climate Finance vs. Requested

This spending bill doesn’t bring the U.S. close to alignment with its G7 partners’ efforts. The European Union already contributes more than $24 billion per year in public climate finance, with an economy approximately three-quarters the size of the U.S. In fact, the amount included in this year’s bill is less climate finance than Spain provides annually, despite having an economy 16 times smaller than the U.S.

Increased U.S. climate funding would:

- provide a cornerstone of U.S. credibility and influence as it seeks to rally the world to address the climate crisis;

- spur concrete actions around the world to reduce emissions quickly enough to keep the goal of 1.5°C (2.7°F) of warming within reach;

- support the poorest countries in the world that have contributed very little to climate change, yet are already facing disproportionately dire impacts;

- help address global and national security threats exacerbated by climate change; and

- create jobs and opportunities for American companies and entrepreneurs in the burgeoning global clean energy market.

PATH AHEAD TO MOBILIZE MORE INTERNATIONAL CLIMATE FINANCE

This spending bill provides the floor for U.S. international climate finance. The yawning holes can be partially addressed through a four-part strategy:

- Find more public resources by prioritizing climate across flexible foreign policy spending (i.e. other funding accounts), ensuring climate is integrated with high integrity into other areas of U.S. foreign assistance, such as health, food, and water; and increasing appropriated climate finance in the next fiscal year.

- Invigorate development finance and credit agencies such as the Development Finance Corporation (DFC), Export-Import Bank (Ex-Im), Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC) and other government agencies that provide climate-related financing to developing countries. Last year, DFC invested around $1.5 billion in developing country climate action, but it could significantly increase this funding. Ex-Im is currently providing funding well below its available capacity. And MCC continues to provide funds, but moves too slowly to mobilize resources for the climate challenge – the gravest challenge in this millennium.

- Secure meaningful reforms at the multilateral development banks (MDBs) to unleash tens of billions more per year for climate action by aggressively implementing the Capital Adequacy Framework (CAF) review recommendations and with the World Bank Group implementing a five-point reform plan.

- Mobilize international financial institutions for greater climate action. Barbados Prime Minister Mottley and other leaders have pushed major reforms of the international financial institutions to create more fiscal space for climate action, address extreme weather in debt repayments, tap into the International Monetary Fund’s Special Drawing Rights, and allow climate vulnerable countries special access for concessional finance. The U.S. has an opportunity to play a leadership role in driving these much-needed reforms given their influential role in these institutions.

In the wake of this inadequate spending bill, the Biden administration now needs to urgently mobilize all these tools and more if it is truly serious about its role in combatting the global climate crisis.

______________________________

i International climate finance is directly appropriated by the U.S. Congress through the “State and Foreign Operations Program” (SFOPs) appropriations act, which funds bilateral programs (e.g., at the State Department and U.S. Agency for International Development) and multilateral climate action (e.g., through the global funds that support the Paris Agreement). Additional international climate spending comes from a variety of other U.S. agencies, including the International Development Finance Corporation (DFC), the Export-Import Bank (Ex-Im), the Millennium Challenge Corporation (MCC), and the Trade and Development Agency (TDA) which have core operating budgets appropriated by Congress, but discretion as to what areas, including climate, to focus their investments. While these latter investments are critical, the directly appropriated climate finance in SFOPs is the cornerstone of U.S. support to tackle the climate crisis. Funding from the multilateral development banks and other international financial institutions aren’t counted toward individual country climate finance targets, so increased funding from these institutions wouldn’t count towards Biden’s $11.4 billion annual finance pledge.