How the U.S. Can Still Meet its Global Climate Finance Pledges

There is a narrow pathway for the Biden Administration to deliver on its international climate finance promises

NRDC/Joe Thwaites

In 2021, President Biden committed to increase U.S. international climate finance to over $11.4 billion per year by 2024. Of this, $3 billion per year was committed to investments in adaptation—historically underfunded—as part of the President’s Emergency Plan for Adaptation and Resilience (PREPARE).

If delivered, this vital funding would spur much-needed emissions reductions in other countries, help the most vulnerable communities who have done the least to contribute to the climate crisis to adapt to its mounting impacts, and protect Americans and people around the world against the physical, economic, and security threats of climate change. It would also reinvigorate U.S. climate leadership, rebuilding trust with developing countries and catching up with other G7 countries who provide much more climate finance relative to their wealth.

In mid-March, Congress finally passed the relevant spending bill for Fiscal Year 2024. It contained just $1 billion in dedicated funding for international climate programs. This is the third year in a row that Congress has failed to sufficiently deliver on U.S. international climate finance commitments. Just $1 billion in a spending package totaling $1.59 trillion sends a damaging message to the rest of the world.

Inadequate international climate spending weakens the U.S., undermining its economic competitiveness in clean energy markets, alienating allies and would-be strategic partners, and ceding diplomatic influence on one of the leading issues shaping international affairs this century. Climate finance is at the center of the “grand bargain” that underpins the Paris Agreement: that all countries need to do more to tackle the climate crisis, but richer countries must support poorer countries to do so. If the U.S. fails to uphold its end of the bargain it will have a hard time rallying other countries to deliver on their commitments.

Though Congress has been unable to come through, the Biden Administration can still deliver on its climate finance promises. Outlined below is the narrow pathway for the administration to still achieve the $11.4 billion goal in Fiscal Year 2024. But first, let’s unpack what Congress did and didn’t include in its FY24 spending package.

What has Congress appropriated for international climate?

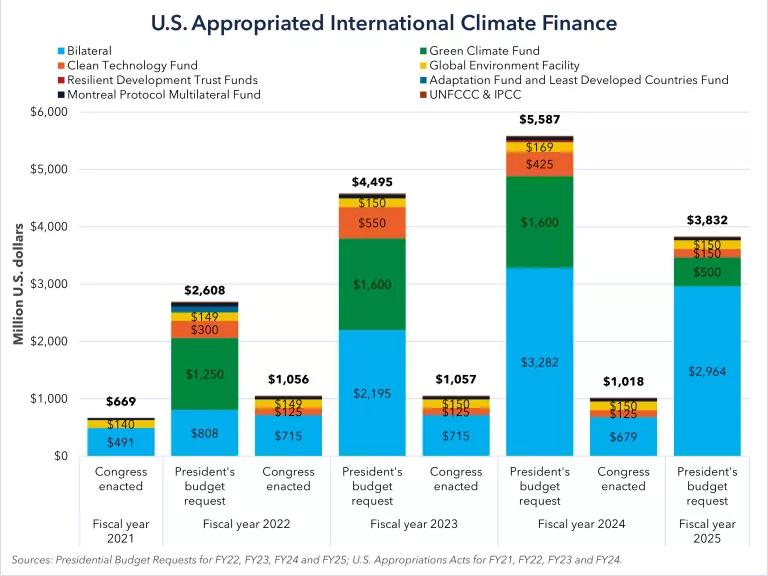

In its FY24 Budget Request, the Biden Administration asked Congress to appropriate over $5 billion dollars in international climate investments for an array of bilateral and multilateral programs to rapidly cut emissions and support vulnerable countries and communities to deal with the disproportionate impacts of climate change.

Yet every year Congress has failed to meet most of the Administration’s international climate finance requests. Even worse, in FY24, Congress cut spending even lower than the disappointing levels in FY22 and FY23, in large part due to the draconian spending caps forced into last year's debt limit legislation.

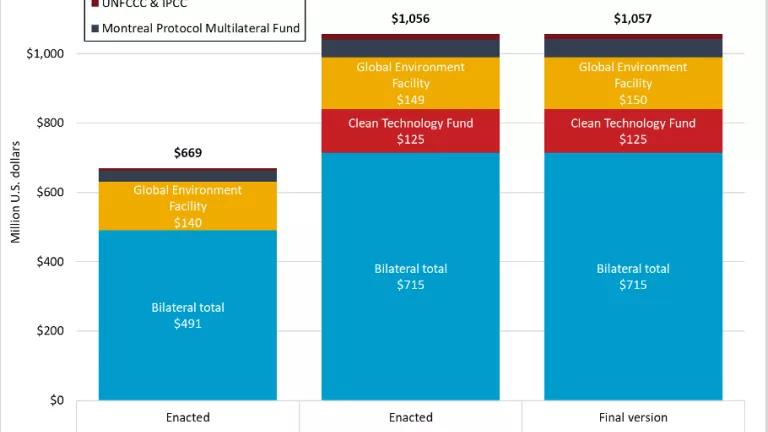

Below is a break-down of the key international climate accounts (figure 1):

Bilateral climate programs focused on adaptation, clean energy, and sustainable landscapes: $679 million appropriated in FY24, $36 million less than FY23. This specifies minimum amounts that the U.S. government must spend on climate programs through agencies such as the Department of State and the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID). Adaptation bilateral programs ($256 million in FY24) support developing countries to reduce the impact of severe weather and climate-fueled disasters on critical infrastructure, agricultural productivity, and public health, among other things. Clean energy programs ($247 million in FY24) support innovation in and deployment of renewable energy and energy efficiency around the world. Sustainable landscapes programs ($176 million in FY24), help protect critical carbon-storing landscapes, including forests and wetlands, including by curbing deforestation.

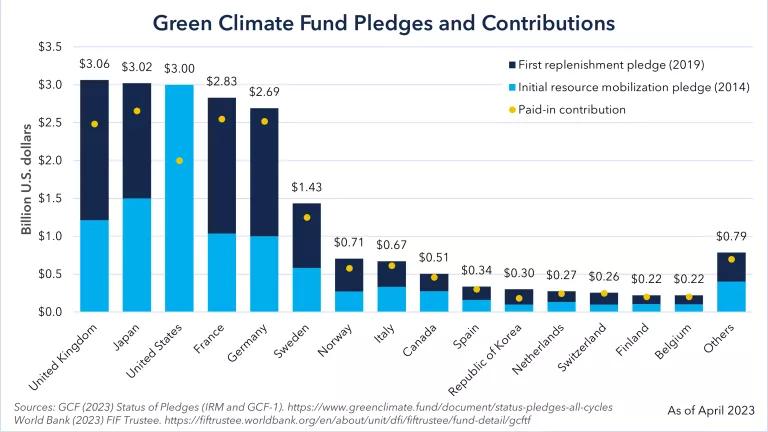

Green Climate Fund (GCF): $0 appropriated in FY24, same as FY23. The Green Climate Fund is the world’s largest multilateral fund focused on climate change. It facilitates transformative investments that reduce emissions and help poorer countries adapt to climate impacts. The GCF has approved almost $14 billion in funding for over 250 projects. These investments are projected to reduce 2.9 billion tones of greenhouse gases, equivalent to the annual emissions of 745 coal power plants, and to increase the resilience of 1 billion people. For every dollar the U.S. invests in the GCF, it leverages $2.8 from other funders and the private sector. In 2014, the Obama administration pledged $3 billion to the Green Climate Fund. The Obama administration delivered $1 billion in 2016 and 2017, and the Biden administration delivered a further $1 billion in 2023, leaving $1 billion outstanding from the decade-old pledge. Last year, the Biden administration renewed the U.S. commitment to the GCF by pledging a further $3 billion to the Fund’s second replenishment.

Clean Technology Fund (CTF): $125 million appropriated in FY24, same level as FY23. This contribution will subsidize a concessional loan to the CTF for its work to accelerate coal power plant retirement and clean energy deployment in major emitting countries.

Global Environment Facility (GEF): $150.2 million appropriated in FY24, same level as FY23. The GEF is the oldest multilateral environmental fund, which support several global environmental conventions, including biodiversity, desertification, mercury and climate. The fund has long enjoyed strong bipartisan support for its work on a variety of environmental challenges. In 2022 the fund underwent its eighth replenishment, raising $5.3 billion in pledges from 29 governments, including emerging economies such as Brazil, China, India and South Africa. This funding will help deliver on the U.S. pledge of $600 million over four years.

Montreal Protocol Multilateral Fund (MLF): $49.3 million appropriated in FY24, $2.6 million less than FY23. This fund supports developing countries to reduce their use of super climate pollutants that are replacing ozone-depleting substances.

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC): $14 million appropriated in FY24, $1 million less than FY23. The IPCC and UNFCCC are the UN’s climate science and negotiating bodies, respectively.

In early March, the Biden administration sent Congress its budget request for Fiscal Year 2025. Responding to the highly constrained caps Congress placed on overall government spending going forward, the administration is asking for only $3.8 billion for international climate accounts, the majority through bilateral channels.

Figure 1: Presidential Budget Requests and Congressional Enactments of U.S. International Climate Finance, Fiscal Years 2021-2025

NRDC/Joe Thwaites

Why is the U.S. saying it is on track to meet the $11.4 billion pledge?

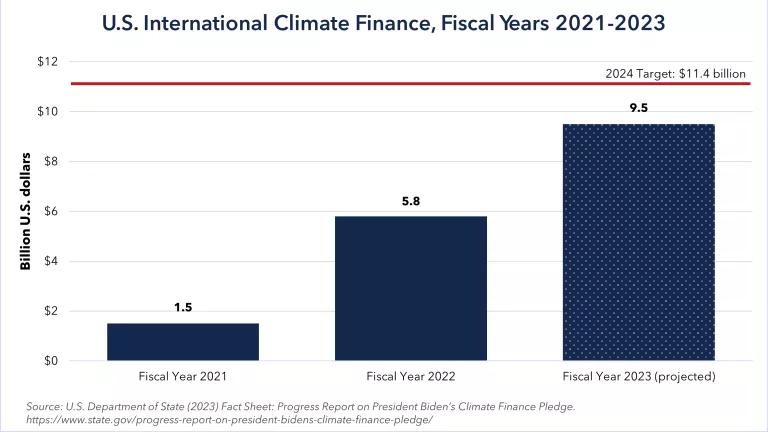

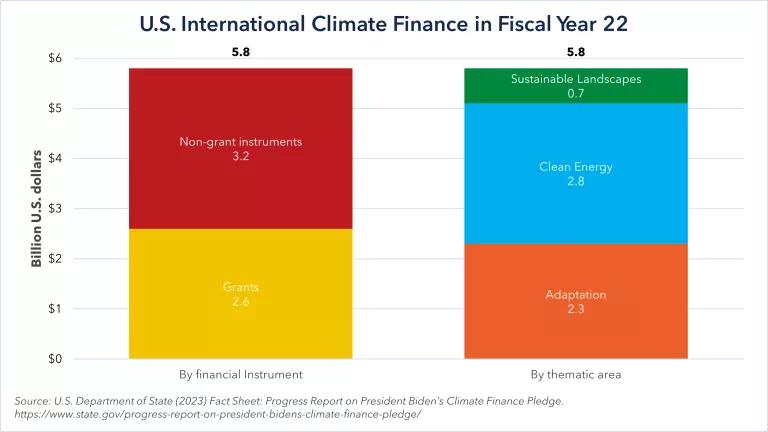

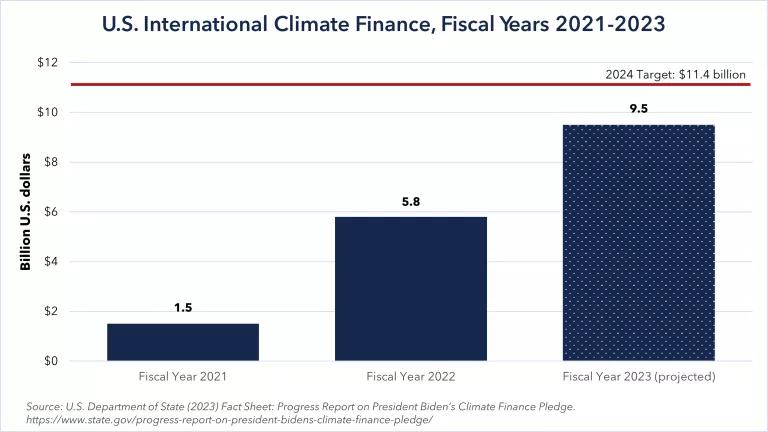

With Congress appropriating less than a tenth of funding towards the pledge of $11.4 billion by 2024, one could be forgiven for giving up hope for meeting the target. Yet during COP28 last year, the State Department released a progress report stating that they were on track to meeting the goal. They reported that in FY22 U.S. international public climate finance increased to $5.8 billion, up from $1.5 billion in FY21 (a budget passed during the prior administration). They included details of how this broke down by financial instrument and thematic area (figure 2). In FY23, they projected U.S. public climate finance would reach $9.5 billion, putting them in striking distance to meet the $11.4 billion goal in FY24 (figure 3).

What is going on?

Figure 2: Breakdown of U.S. international climate finance in 2022 by financial instrument and thematic area

NRDC/Joe Thwaites

Figure 3: U.S. International Climate Finance, Fiscal Years 2021-2023

NRDC/Joe Thwaites

The key dynamic to understand is that Congressional appropriations are a floor rather than a ceiling on funding. Congress sets minimum amounts to be invested in combatting the climate crisis globally through specified funds, and the administration can and is doing more with flexible accounts and agencies that have discretion to do more to support global climate action.

The numbers the State Department reports are based on what all arms of the U.S. government actually end up doing—it includes the $1 billion per year Congress appropriated, but also the significant efforts pursued across agencies to scale up climate investments from their discretionary financing. This is good news, and the administration must use every lever it has available to ensure they meet their climate finance targets.

What more needs to happen to hit the U.S. pledge?

In addition to continuing to work with Congress to appropriate enhanced climate investments, here are three key areas the administration must focus on to deliver the $11.4 billion pledge in FY24, which runs through September:

- Push USAID, the State Department, and other international development agencies to further prioritize climate projects and integrate climate considerations across their portfolios. In addition to spending the minimum amounts that Congress directs towards bilateral climate programs, all agencies involved in development projects should be actively integrating climate into everything they do—especially their programs and budgets. This isn’t just about hitting a financial pledge; considering how development projects will impact climate and how the effects of the climate crisis will impact projects is, at its core, just smart development practice. Projects that fail to take into account projected climate impacts—such as more frequent and intense flooding or droughts—are more likely to fail. And given the speed with which the world needs to transition to net zero emissions, it is more likely to be cost effective to incorporate low- or zero-emissions technology and adaptive capacity into projects from the beginning rather than coming back at a later date to do retrofits or early retirement of assets. USAID has made progress in scaling up its climate integration across development programs in recent years, and should be pushed to do more. The State Department should also bolster climate investments across its portfolio, particularly in regional budgets as well as functional areas such as health, economic development, gender, agriculture, and democracy.

Support the U.S. International Development Finance Corporation (DFC) to scale up its climate investments in developing countries toward $5 billion in FY24. DFC was created in 2019 from a merger of the Overseas Private Investment Corporation and USAID’s Development Credit Authority, with the aim of creating a modernized and competitive U.S. development finance institution. The transition to zero carbon economies is the major growth story of the 21st century, which DFC can play a central role in driving.

To be competitive, DFC needs to fully commit to the clean economy of the future and not prop up the fossil industry of the past. In 2021, DFC set a target that a third of its overall investments will go to climate from FY23 onwards. It handily exceeded this goal, reaching 40% for climate in FY23 ($3.7 billion out of $9.3 billion in total financing). Some of this $3.7 billion was invested in developed countries, so wouldn’t entirely count towards the $11.4 billion goal. And DFC can be setting its ambitions even higher. Last year DFC approved $4 billion for modular nuclear reactors; they should be able to commit at least the same amount for renewable energy, storage and grids. And DFC must be equipped with the tools to scale up investments in adaptation to ensure the PREPARE target of $3 billion by FY24 is achieved.

DFC is hampered from unlocking the full potential of its balance sheet by antiquated budgetary rules, which require that any equity investments the agency makes are recorded as if they were grants, with no accounting for the expected financial returns. Meanwhile loans are rightly budgeted much lower than their face value based on their expected reflows. This acts as a massive disincentive to using equity, even though one of the major innovations in the creation of DFC was allowing it to take equity positions like peer agencies around the world routinely do, and project developers routinely demand. Congress has an opportunity to address these budgeting rules and provide additional much-needed tools when DFC comes up for reauthorization next year.

Make the Export-Import Bank (EXIM) comply with U.S. policy to end overseas financing for fossil fuels and shift it into clean energy. EXIM is the U.S.’s export credit agency, helping American companies export goods and services to overseas markets. EXIM has a dismal track record when it comes to energy investments, investing far more in fossil fuels than clean energy. In 2021, the Biden administration issued guidance restricting U.S. agencies from using public money to finance fossil fuels internationally, except in extremely limited circumstances, and joined international commitments to end international public support for unabated fossil fuel energy by the end of 2022 and shift funding to clean energy. Yet EXIM’s leadership does not appear to be adhering to these policies. In recent months, they have approved hundreds of millions in public funding for multiple fossil fuel projects in major petrostates such as Bahrain that are hardly short on cash. Since the end of 2022 deadline, EXIM has approved nearly $1.3 billion for 5 fossil fuel projects.

In FY23, just 10% of EXIM’s approved financing of $8.8 billion went to renewable energy. This came from a single $900 million transaction for solar photovoltaics in Angola. EXIM should be doing multiple such renewable projects each year; if it focused more on clean energy and other climate-positive investments it could make a significant contribution to the $11.4 billion commitment. But if EXIM leadership continues its apparent flouting of U.S. policy by financing fossil fuel projects, Congress should consider taking action on this front.

The Administration must seize this narrow window of opportunity

Ideally, Congress would directly appropriate much more for international climate finance. Direct appropriations are key for securing more grant-based financing, which is important for projects that may not generate a reflow on investment, such as those helping low-income and vulnerable countries deal with the impacts of climate change.

President Biden’s FY25 budget request again sets out critical international investments to act on climate in greater alignment with what science demands and support the most vulnerable to adapt to destructive climate impacts they didn’t cause and can’t avoid. And Congress should approve this funding.

However, the Biden administration does not need to only rely on Congress. It can still deliver on its climate finance pledges by ensuring all the agencies involved in international financing receive clear direction to prioritize scaling climate investments. The State Department’s reporting shows that this approach can pay dividends, coming within striking distance of the FY24 pledge in FY23. The FY24 appropriations act slashed international climate finance from already low levels, putting the wind against them. This reinforces the need to guide agencies to do more with their flexible resources.

U.S. international climate finance decision making is not happening in a vacuum; other countries are ramping up their international investments in climate action. The U.S. must keep pace, otherwise it will diminish its influence and access to booming clean technology export markets. To seize the myriad benefits and stem the risks, the U.S. must significantly increase its investments to drive the necessary global transformations during this decisive decade for the climate.

America has started to make real progress in investing in domestic climate action. It is high time for the U.S. to make commensurate investments to meet the global scale of the challenge.