Preparing for Hurricanes: Infrastructure & Our Health

To be truly climate-smart and protective of our health, infrastructure policies and projects need to account for the inequitable burdens of disruptions such as power outages.

Part two of a three-part series. Please be aware that following contains discussions of death and other difficult health topics.

It’s National Hurricane Preparedness Week, a time to reflect on readiness for the start of the Atlantic hurricane season on June 1—and for the worsening hurricane seasons of the future.

In my last post, I covered some of the major improvements we need to make to our public health systems to protect people from hurricane-related harms. Let’s now turn to how hurricanes harm health by damaging and disrupting essential infrastructure such as the electric grid and hospitals.

Heat-related illnesses and deaths

The hot-weather season and hurricane season already overlap in the eastern United States. However, climate change is boosting the chance that heat wave disasters will make the aftermath of hurricanes even deadlier. That’s happened at least twice in the last four Atlantic hurricane seasons, when 17 people in Florida and eight people in Louisiana died from heat-related illnesses after hurricanes Irma (2017) and Laura (2020), respectively.

Downed power poles after Hurricane Laura (2020).

Extreme heat immediately following a hurricane is obviously more dangerous when households and hospitals don’t have electricity to power fans and air conditioning. For example, heat made it harder for doctors in Puerto Rico to care for seriously ill patients and pregnant people after Hurricane Maria (2017) knocked out much of the island’s electric grid for 11 months.

Inability to use medical equipment

More than 685,000 people in the United States depend on electricity-powered medical equipment such as wheelchairs, dialysis machines, and ventilators. Loss of electricity after a hurricane can mean anything from poor quality sleep to death for those individuals. After Hurricane Irma, older adults across South Florida were trapped in their own apartment buildings when power outages left them without working elevators and wheelchairs.

Gasoline and carbon monoxide poisoning

For households that can afford them and know how to use them, back-up electricity generators can be lifesavers in the wake of a hurricane. But generators worsen local air pollution if they run on fossil fuels. They also can be deadly if operated incorrectly, leading to carbon monoxide poisoning, gasoline poisoning, or even explosions.

After Hurricane Sandy (2012), for instance, the New Jersey Poison Information and Education System received 100 calls for carbon monoxide exposure and 160 calls for gasoline exposure. After Hurricane Laura, nearly half of the initial wave of deaths in Texas and Louisiana were due to carbon monoxide.

A member of the National Guard delivering a generator after Hurricane Dorian (2019).

Delayed or insufficient medical care

Extended power outages also make it harder for people to self-manage chronic illnesses and receive timely medical care. For example, e-prescriptions in Texas, Florida, and Puerto Rico declined in the days immediately after Hurricanes Harvey, Irma, and Maria, respectively. Although volumes returned to normal in Texas and Florida after a few days, access to e-prescriptions in Puerto Rico still hadn’t fully recovered eight months after Maria.

And, of course, the electric grid isn’t the only infrastructure that can make or break access to medical care. Flooded roads, damaged buildings, unsafe water supplies, and other infrastructure disruptions also create barriers to care, especially for people with mobility challenges or chronic conditions. In a small study from a low-income county in North Carolina, diabetes patients reported trouble getting the food, test strips, medications, and doctor visits they needed after hurricanes Matthew (2016) and Florence (2018), especially if they had evacuated to a shelter. The prevalence of diabetic ketoacidosis, a severe complication of diabetes, more than doubled at one regional network of health facilities after Matthew.

Flooding in North Carolina after Hurricane Matthew (2016).

What needs to change?

The examples listed above point to the need for an ambitious, expedited effort to prepare America’s communities for weather extremes such as hurricanes. America’s physical infrastructure, from highways and bridges to our public water systems, is not ready for the rigors of increasingly dangerous hurricane seasons, despite recent improvements in states such as Florida. There’s an urgent need to strengthen both structures such as power poles and bridges, and the processes by which we operate existing structures and plan to build new ones.

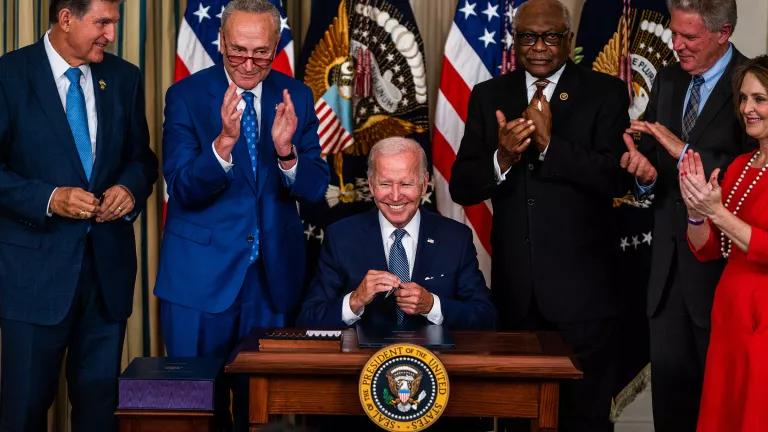

One essential first step is embedding climate change in every major decision about infrastructure, rather than planning for the disasters of the past. More on that below. But even that won’t be enough to protect the low-income communities and communities of color most vulnerable to climate change. To be truly climate-smart, infrastructure policies and projects need to undo decades of systematic disinvestment in those communities and account for the inequitable burdens of disruptions such as power outages. President Biden has announced plans, including the American Jobs Plan, that start the nation on the path to these goals. More on that below.

Here are just two of the major changes we need to prioritize now.

A more resilient electric grid that serves the needs of vulnerable populations

As my colleague John Moore recently wrote about the winter storm disaster in Texas:

“With the right planning and policy choices, we can do better than holding much of the system together with virtual duct tape and bailing wire”

Unfortunately, California has one of the only requirements in the nation for utilities to account for climate change in infrastructure and service planning. That’s a problem in the context of hurricanes and other severe storms. But it’s also becoming a day-to-day health danger during heat season as temperatures soar and utilities scramble to meet increased demand for cooling.

One of the immediate ways to strengthen community resilience to hurricanes is to build microgrids—small, interconnected clean energy systems that are paired with battery storage. For example, hundreds of distributed solar energy-plus-storage systems have been installed since Hurricane Maria in Puerto Rico. Early results suggest these systems have already improved household health, been more reliable than diesel generators, and helped protect access to clean water and sanitation during power outages.

President Biden’s American Jobs Plan makes three important commitments to help advance better long-term planning and community resilience measures: ensuring “every dollar” of federal infrastructure spending improves resilience to climate change, rebuilding beyond existing codes and standards, and targeting investments to vulnerable communities.

More robust climate adaptation planning and implementation in hospitals and other critical healthcare facilities

Hurricane readiness is no easy task for healthcare facilities, in part because they depend heavily on other critical infrastructure. Even when a hospital successfully minimizes flood damage and power disruptions within its walls, infrastructure damage outside its walls can shut down operations. That very thing happened in Louisiana when Hurricane Laura compromised hundreds of public water systems. Nurses at one hospital had to flush toilets with floodwater they collected from the road before the facility was eventually evacuated.

Healthcare facilities can assess their vulnerability to hurricanes and other climate-related hazards with resources such as the U.S. Climate Resilience Toolkit or these checklists from the World Health Organization. However, addressing each vulnerability on the checklist represents a major project in itself, and the health care sector has received just a tiny fraction of total U.S. investments in climate adaptation measures.

Congress and the Biden administration should heed recent climate resilience recommendations from hospital leaders and other health professionals. This includes updating the Healthcare and Public Health section of the National Infrastructure Protection Plan with a more robust consideration of climate change, and increasing adaptation funding and technical support directly to health facilities.

Community Health Centers, which increase access to primary care and emergency services to the most vulnerable among us, particularly need help. A study after Hurricane Harvey found seven hospitals and 40 community health centers in the lowest-income Houston communities, which also tended to have more people of color. The wealthiest, whitest communities on the other hand, had 46 hospitals and 13 health centers. Community health centers often operate on a thinner margin than hospitals, making it harder for them to plan for disasters next week—let alone those a decade from now.

A community health center damaged by Hurricane Sandy (2012). Staff worked in the flooded building without heat to serve vulnerable community members after the storm.

In my last post of this series, I’ll talk about the role of climate-smart social infrastructure in protecting our health from hurricanes and tropical storms.