Preparing for Hurricanes: Social Infrastructure & Health

Last post of a three-part series. Please be aware that following contains discussions of suicide and other difficult health topics.

We’re less than two weeks away from the start of what could be yet another busy Atlantic hurricane season. In my two previous posts, I explored some of the ways hurricanes and tropical storms affect our health and how strengthening our public health system and physical infrastructure can help. Now I’ll turn to support needed for the workers and services required to promote community health and well-being, also known as social infrastructure.

The United States is still recovering from the COVID-19 pandemic as we approach this year’s hurricane season. Landlords in hurricane-prone cities such as Houston and Tampa have filed for tens of thousands of evictions in just the last two months. Food insecurity nationwide spiked upward in 2020 from a more than 20-year low and will remain elevated this year, especially in southeast states such as Louisiana and Texas. And medical debt is increasing across the country, driven in part by people losing their employer-sponsored health insurance.

Facts like these point to a sobering reality: COVID-19 has swollen the ranks of people who can’t afford to hurricane-proof their home (if they have a home at all), stock up on supplies, or evacuate ahead of a major storm. That means many more people will be vulnerable to the post-hurricane health harms that arise from the overlapping harms of poverty, a weak social safety net, and disinvestment in Black and brown communities.

Food insecurity

Far too many people in America have a poor-quality diet or go hungry because of economic hardship or lack of access to sources of healthy food. Not having enough quality food to eat is associated with many poor health outcomes, including developmental delays in children, increased likelihood of depression and suicidal thoughts, and exacerbation of chronic illnesses such as diabetes.

Added to this, storm-related disruptions such as power outages, school closures, damage to grocery stores, and loss of access to vehicles or public transportation can create short term food shortages for any household. But for people who suffer major property losses, medical hardship, and losses of jobs or income during or after a hurricane, food insecurity can last for years.

Food insecurity disproportionately affects Black and Latino households. More than a year after Hurricane Harvey (2017), for example, the odds of food insecurity in 41 Texas counties was about 2.5 times higher among Black residents than white residents. Latinos had nearly double the odds of food insecurity compared to whites.

In New Orleans, Hurricane Katrina (2005) deepened existing disparities in access to supermarkets between majority-Black and other neighborhoods. It took four years for the gap to return to pre-Katrina levels, and another five years before majority-Black neighborhoods had comparable access to those that were majority white or mixed race.

Housing insecurity

Housing safety, availability, and affordability are major determinants of health. Hurricanes can therefore have an indirect effect on health—particularly for low-income people and people of color—by damaging homes, reducing the number of housing units, and driving up prices.

In the Houston region, for example, communities of color were more likely to have severe housing damage after Hurricane Harvey. For every 1 percent increase in the concentration of Latino residents, total damages increased by up to 13.5 percent. For the same increase in Black residents, damages increased by up to 16.1 percent. This may be due to a combination of living in more flood-prone areas, poorer quality housing, and having fewer resources to flood-proof homes ahead of the hurricane.

Post-Harvey surveys also showed that Black and Latino residents were more likely to report trouble getting help. This is consistent with an accumulating body of evidence that the U.S. system for assisting people after disasters is deeply inequitable. In one new analysis of 14 years’ worth of disbursements from the Federal Emergency Management Agency’s (FEMA) Individuals and Households Program, researchers found that renters with the greatest social vulnerability were not typically the ones who got the most assistance. Among homeowners, Black and Asian communities were less likely to get assistance than white ones.

Unsafe (and unpaid) work

People of color are disproportionately represented in the industries and low-wage jobs that clean up and rebuild after a disaster. That work is dirty and dangerous, putting workers at risk of injury, heat-related illness, and death. The situation is made worse when federal or state safety inspectors dial back on enforcement in a misguided attempt to speed up response and recovery efforts.

Immigrant workers are particularly vulnerable to unsafe employer practices due to language barriers, discrimination in the workplace, possible concerns about immigration status, and more. In addition, these workers frequently face wage theft after disasters. One recent example comes from the Florida Keys. After Hurricane Irma (2017), workers cleaning up two luxury resorts were regularly denied pay or given checks that bounced. According to a now-settled lawsuit, the employer’s representative:

“attempted to silence [the workers] by threatening to ‘send immigration to your house.’ He repeated his threat to report the workers to immigration police, if they continued to ask for their pay.”

What needs to change?

I can’t do justice here to all the solutions needed for the thorny problems outlined above. Addressing them fully will require nothing less than transformation of our economy, our housing and transportation systems, and the way we manage disasters.

However, here are a few places to start.

Build and diversify the climate resilience workforce

One of the beautiful things we see after major hurricanes is neighbors helping neighbors, from volunteer search and rescue crews, to disaster pantries, to mutual aid networks. As Dr. Natalie Simpson, a disaster response expert at the University of Buffalo put it:

“If you're talking about a sudden large-scale disaster, there will never, ever, ever be enough professional first responders right when they're needed, right when a disaster strikes. Everybody is a first responder.”

It may be true that we’ll never have enough responders, but the current situation is unacceptable. Take FEMA, for example, the lead federal agency for disasters. FEMA has been short on qualified staff since at least the devastating 2017 hurricane and wildfire seasons. This year could be even worse than 2017, in part because of the COVID-19 pandemic.

At the local level, governments and the private sector should professionalize the work done by volunteer responders in affected communities by creating pathways for family-supporting jobs and careers in climate resilience. One of the many benefits of building this local capacity would be a more diverse and culturally-competent emergency management workforce, which currently is overwhelmingly white and male.

Protect worker health and safety

Disaster response and recovery workers need far better protections on the job than they get now. This includes, among other things, better training for workers, access to appropriate and sufficient protective equipment, and for the Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) to beef up enforcement after disasters instead of just providing technical assistance to employers.

It also includes an emergency standard for COVID-19, which is now two months late. Despite a sudden shift last week to a nearly mask-free world by the White House and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the pandemic isn’t over—particularly for the Black and brown and low-wage “essential workers” who live in communities without equitable access to vaccines.

Ensure that climate and health adaptation plans tackle intersecting threats—and that they’re fully funded

Here’s the bottom line: The health harms of hurricanes and other climate-related disasters go well beyond the direct effects of wind and water. To keep people healthy and safe, we need to climate-proof our housing, food, health care, transportation, occupational safety standards, and all the other essential services and systems on which we rely.

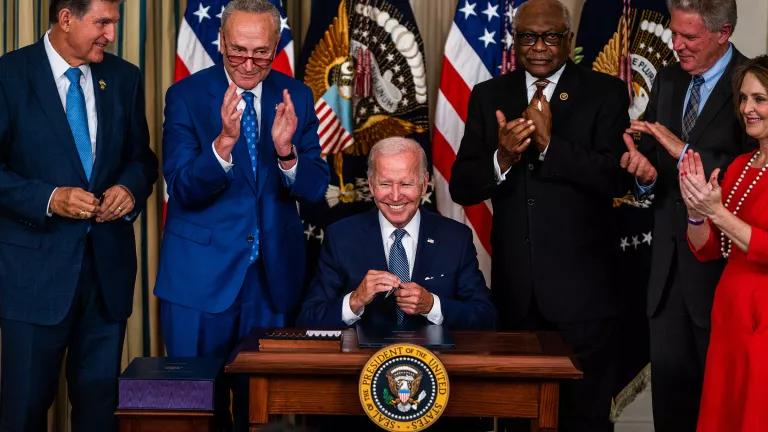

This means that climate adaptation plans all the way from the federal government to individual city councils need to (a) embody the coordinated, whole of government approach touted by the Biden administration; and (b) tackle the systemic inequities that make communities vulnerable in the first place to the health harms of climate change.

Finally, adaptation plans aren’t sufficient without the funding and workers to get them implemented. As a recent global review of urban adaptation planning noted:

“To be credible, adaptation plans should also assign economic resources to implementation and monitoring. In our sample, planning documents tend to omit information regarding budget for the implementation, and when they include it, information is not measure-specific, which inhibits effective resource assignation and implementation.”

Everyone who lives in a hurricane-prone region must prepare to the best of their ability. But personal preparation simply won’t be enough as climate change makes hurricanes fiercer and deadlier. We need to stitch our current scraps of climate preparedness into a cohesive whole, to create the strongest, most protective safety blanket possible.