Drought: Everything You Need to Know

Drought affects more people globally than any other natural disaster. Here’s what causes these prolonged dry spells and how we can mitigate their impact.

Herr Olsen/Flickr

Natural disasters usually announce their arrival: Hurricanes uproot trees, tornadoes roar, and wildfires wipe out entire landscapes. These large, sudden events generate destruction on impact—and then they’re gone.

Drought is different. It doesn’t make a big entrance—the start of a drought might even be mistaken for a bit of a dry spell—and its impact builds over time. But while often described as a “creeping disaster,” drought leaves a trail of destruction as dangerous and deadly as any other extreme weather event. In fact, drought has affected more people around the world in the past four decades than any other type of natural disaster.

Here’s a look at what drought is, what causes it, and how we can better prepare for its impact.

What is drought?

Drought is characterized by a lack of precipitation—such as rain, snow, or sleet—for a protracted period of time, resulting in a water shortage. While droughts occur naturally, human activity, such as water use and management, can exacerbate dry conditions. What is considered a drought varies from region to region and is based largely on an area’s specific weather patterns. Whereas the threshold for drought may be achieved after just six rainless days on the tropical island of Bali, annual rainfall would need to fall below seven inches in the Libyan desert to warrant a similar declaration.

Developing nations are particularly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change, including drought. More than 80 percent of drought-induced economic damage and loss suffered by developing nations from 2005 to 2015 was related to livestock, crops, and fisheries. The economic toll of some $29 billion tells only part of the story. Drought in developing nations is notorious for creating water and food insecurity and exacerbating preexisting problems such as famine and civil unrest. It can also contribute to mass migration, resulting in the displacement of entire populations.

A refugee camp in Kenya

IHH Humanitarian Relief Foundation/Flickr

In the United States, drought is the second-most costly form of natural disaster (behind hurricanes), exacting an average toll of $9.6 billion in damage and loss per event, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration's (NOAA) National Centers for Environmental Information. Meanwhile, some level of drought often has some part of the country in its grip. During the historic dry spell of 2012 (the nation’s most extensive since the 1930s), as much as two-thirds of the country was affected by drought at its peak. U.S. droughts can be persistent as well. From 2012 to 2016, scant rainfall and record-breaking heat in California created what is estimated to have been the state’s worst drought in 1,200 years.

These dry spells take a major toll on the economy, with the drought and extreme heat of 2012 alone resulting in an estimated $17 billion in crop losses. As in developing nations, they can create conditions of water insecurity and higher food prices. Drought can also lead to regionally specific problems. In California, for example, a large number of native fish populations that depend on the San Francisco Bay–Delta Estuary—from the bellwether delta smelt to the iconic Chinook salmon—have suffered sharp declines due to reduced river flows during the recent historic drought.

Types of drought

Droughts are categorized according to how they develop and what types of impact they have.

Drought damage on the Fresno Harlen Ranch in Fresno, California

Cynthia Mendoza/USDA

Meteorological drought

Imagine a large swath of parched, cracked earth and you’re likely picturing the impact of meteorological drought, which occurs when a region’s rainfall falls far short of expectations.

Agricultural drought

When available water supplies are unable to meet the needs of crops or livestock at a particular time, agricultural drought may ensue. It may stem from meteorological drought, reduced access to water supplies, or simply poor timing—for example, when snowmelt occurs before runoff is most needed to hydrate crops.

Hydrological drought

A hydrological drought occurs when a lack of rainfall persists long enough to deplete surface water—rivers, reservoirs, or streams—and groundwater supplies.

Causes of drought

Natural Causes

Droughts have plagued humankind throughout much of our history, and until recently they were often natural phenomena triggered by cyclical weather patterns, such as the amount of moisture and heat in the air, land, and sea.

Fluctuating ocean and land temperatures

Ocean temperatures largely dictate global weather patterns, including dry and wet conditions on land, and even tiny temperature fluctuations can have huge ripple effects on climate systems. Research shows that dramatic and prolonged temperature changes in the North Pacific and North Atlantic Oceans correspond directly to extreme weather patterns on land, including persistent droughts in North America and the eastern Mediterranean—the latter of which has been described as the region’s worst drought in 900 years. Fluctuating ocean temperatures are also behind El Niño and La Niña weather phenomena, with La Niña notorious for drying out the southern United States. Meanwhile, hotter surface temperatures on land lead to greater evaporation of moisture from the ground, which can increase the impact of drought.

Altered weather patterns

The distribution of rainfall around the world is also impacted by how air circulates through the atmosphere. When there is an anomaly in surface temperatures—particularly over the sea—air circulation patterns are altered, changing how and where precipitation falls around the world. The new weather patterns can throw water supply and demand out of sync, as is the case when earlier-than-usual snowmelt reduces the amount of water available for crops in the summer.

Reduced soil moisture

Soil moisture can impact cloud formation, and hence precipitation. When water from wet soil evaporates, it contributes to the formation of rain clouds, which return the water back to the earth. When land is drier than usual, moisture still evaporates into the atmosphere, but not at a volume adequate to form rain clouds. The land effectively bakes, removing additional moisture and further exacerbating dry conditions.

Manmade Causes

While drought occurs naturally, human activity—from water use to greenhouse gas emissions—is having a growing impact on their likelihood and intensity.

Climate change

Climate change—and global warming, specifically—impacts drought in two basic ways: Rising temperatures generally make wet regions wetter and dry regions drier. For wetter regions, warm air absorbs more water, leading to larger rain events. But in more arid regions, warmer temperatures mean water evaporates more quickly. In addition, climate change alters large-scale atmospheric circulation patterns, which can shift storm tracks off their typical paths. This, in turn, can magnify weather extremes, which is one reason why climate models predict the already parched U.S. Southwest and the Mediterranean will continue to get drier.

Excess water demand

Drought often reflects an imbalance in water supply and demand. Regional population booms and intensive agricultural water use can put a strain on water resources, even tipping the scale enough to make the threat of drought a reality. One study estimates that from 1960 to 2010, the human consumption of water increased the frequency of drought in North America by 25 percent. What’s more, once rainfall dwindles and drought conditions take hold, persistent water demand—in the form of increased pumping from groundwater, rivers, and reservoirs—can deplete valuable water resources that may take years to replenish and permanently impact future water availability. Meanwhile, demand for water supplied by upstream lakes and rivers, particularly in the form of irrigation and hydroelectric dams, can lead to the diminishing or drying out of downstream water sources, which may contribute to drought in other regions.

Drought-stricken Lake Powell, seen from space

NASA

Deforestation and soil degradation

When trees and plants release moisture into the atmosphere, clouds form and return the moisture to the ground as rain. When forests and vegetation disappear, less water is available to feed the water cycle, making entire regions more vulnerable to drought. Meanwhile, deforestation and other poor land-use practices, such as intensive farming, can diminish soil quality and reduce the land’s ability to absorb and retain water. As a result, soil dries out faster (which can induce agricultural drought), and less groundwater is replenished (which can contribute to hydrological drought). Indeed, experts believe the 1930s Dust Bowl was caused in large part by poor agricultural practices combined with the cooling of the Pacific and the warming of the Atlantic by as little as a few tenths of a degree.

Are droughts increasing?

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) did not see a global trend toward increasing dryness or drought across the world in 2013, when it released its most recent assessment. But global temperatures have unequivocally become hotter, and hotter conditions precipitate extreme weather—including severe drought. Hotter conditions also reduce snowpack, which provides a key source of water supply and natural water storage in many regions. Regionally, the driest parts of the earth are getting drier, while the wettest parts are getting wetter. That’s why some areas of the world, such as southern Europe and West Africa, have endured longer and more intense droughts since the 1950s while other regions, such as central North America, have seen droughts become less frequent or less intense. Looking forward, as temperatures continue to rise, the IPCC and other researchers anticipate an intensification of those regional trends.

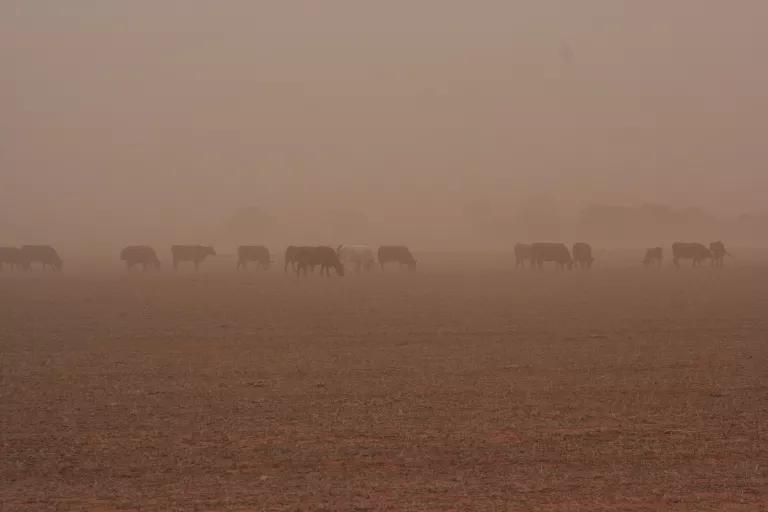

Cattle farm near Walkaway, western Australia

Jackocage/Flickr

Drought prevention and preparation

We can’t control the weather. But by limiting our climate change contributions, reducing water waste, and using water more efficiently, we can prepare for—and maybe even curb—future dry spells.

Climate change mitigation

The impact of climate change, including more severe drought, can be mitigated only when countries, cities, businesses, and individuals shift away from the use of climate-warming fossil fuels to cleaner renewable energy sources. The Paris Agreement, which was adopted by nearly every nation in 2015 and aims to limit the earth’s warming over the next century to 2 degrees Celsius, or 1.5 degrees if possible, lays the framework for global climate action. But the current commitments countries made under the pact so far aren’t considered enough to limit global warming to 2 degrees Celsius. It will succeed only if countries go beyond their commitments, and that includes the United States. However, catering to big polluters instead of the will of a majority of Americans, the Trump administration had committed to withdrawing the country from the agreement, as well as from key domestic policies—from the Clean Power Plan to automotive fuel efficiency standards—that would reduce our nation’s carbon emissions. Fortunately, American states and cities, as well as more than 2,000 U.S. businesses, institutions, and universities, are taking the reins on climate action by reducing emissions and increasing energy efficiency. It’s crucial that they do, as research indicates even meeting the agreement’s most ambitious targets will only reduce—not eliminate—the likelihood of extreme weather events.

There’s plenty of room for individuals—particularly Americans, who produce about four times more carbon pollution than citizens elsewhere, on average—to fight climate change as well. Actions include speaking to local and congressional leaders about regional environmental policies and finding ways to cut carbon pollution from your daily life.

Urban water conservation and efficiency

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) estimates that aging infrastructure—faulty meters, crumbling pipes, leaky water mains—costs the United States an estimated 2.1 trillion gallons in lost drinkable water each year. (That’s about enough to drown Manhattan in 300 feet of water.) Meanwhile, a single leaky faucet—releasing just three drips a minute—wastes more than 100 gallons of water in a year. States, cities, water utilities, businesses, and citizens can curb water waste by investing in climate-smart strategies. These include repairing leaky infrastructure (from utility pipes to the kitchen faucet), boosting water efficiency with the use of water- and energy-efficient technologies and appliances (such as clothes washers), and adopting landscape design that makes use of drought-tolerant plants and water-efficient irrigation techniques. In California, these strategies alone could reduce water use by as much as 60 percent. For individuals, there are many other ways to conserve water as well.

Water recycling

Recycled water—also called reclaimed water—is highly treated wastewater that can be used for myriad purposes, from landscape irrigation (such as watering public parks and golf courses) to industrial processes (such as providing cooling water for power plants and oil refineries) to replenishing groundwater supplies. Graywater—recycled water derived from sinks, shower drains, and washing machines—can be used on site (for example, in homes and businesses) for non-potable uses such as garden or lawn irrigation. Recycled water can serve as a significant water resource, reducing demand from sources such as rivers, streams, reservoirs, and underground water supplies. According to California’s Department of Water Resources, recycling has the potential to increase water supply in the state by as much as 750 billion gallons a year by 2030.

Stormwater capture

Every year in the United States, about 10 trillion gallons of untreated stormwater washes off paved surfaces and rooftops, through sewer systems, and into waterways. Not only does this create pollution problems (as contaminants from land get flushed into rivers, lakes, and oceans), but it reduces the amount of rainwater that soaks back into the earth to replenish groundwater supplies. The use of green infrastructure—including green roofs, tree plantings, rain gardens, rain barrels, cisterns, and permeable pavement—can increase water supplies substantially. Stormwater capture in urban Southern California and the San Francisco Bay region alone could potentially increase annual water supplies by as much as 205 billion gallons.

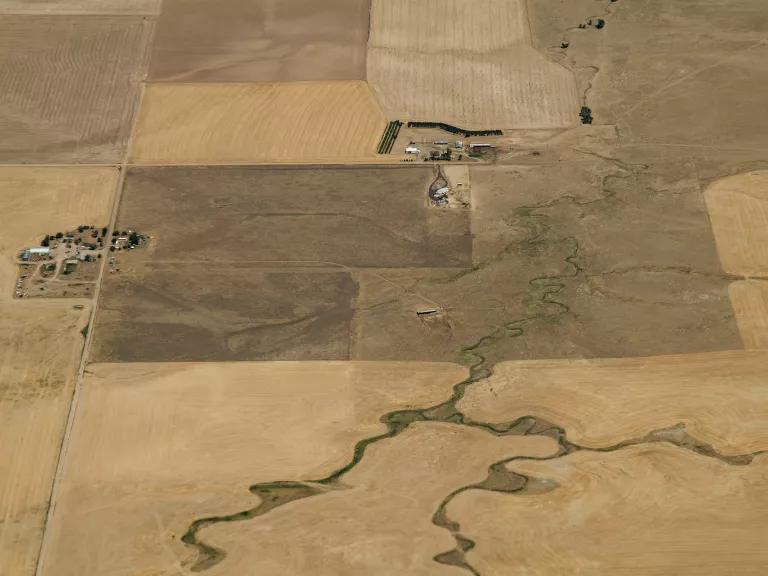

Farms affected by drought near Strasburg, Colorado

Lance Cheung/USDA

Agricultural water conservation and efficiency

Agriculture is the largest consumer of the earth’s available freshwater, accounting for 70 percent of withdrawals globally, according to the World Bank. Strategies for better water management in the agricultural sector focus on increased water efficiency and reduced consumption. These include improved irrigation techniques—such as switching from flood to drip irrigation, which alone can cut water use by about 20 percent—as well as more precise irrigation scheduling to adjust the amount of water used at different stages of crop growth. Meanwhile, crop rotation, no-till farming (a method for growing crops with minimal soil disturbance), and the use of cover crops help build soil health, which in turn enables the land to absorb and retain more water. Indeed, the use of cover crops alone on just half the land used to grow corn and soybeans in 10 of America’s highest-producing agricultural states would help the soil retain as much as a trillion gallons of water each year.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

We need climate action to be a top priority in Washington!

Tell President Biden and Congress to slash climate pollution and reduce our dependence on fossil fuels.

What Are the Solutions to Climate Change?

Climate Tipping Points Are Closer Than Once Thought

What Are the Effects of Climate Change?