Four Environmental Justice Champions You Should Know

Whether they are delivering food or climate justice or standing up for clean air or access to nature, these activists are uplifting communities across the country.

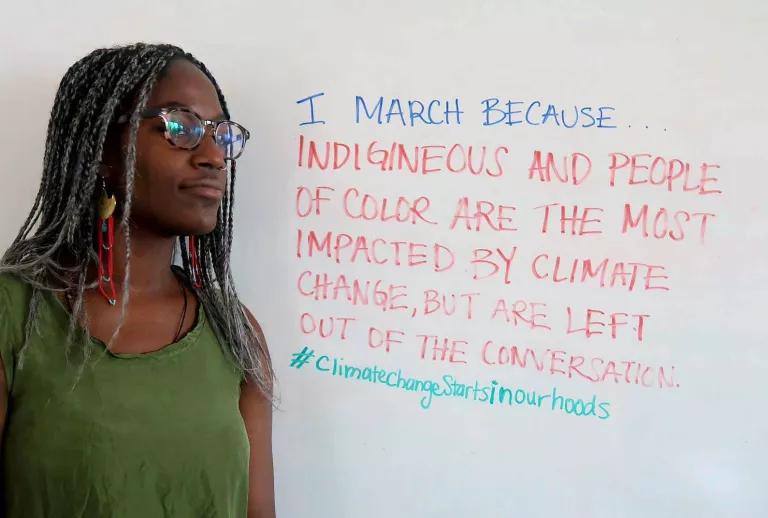

Clockwise from top left: Dior Doward, Bakeyah Nelson, Taylor Thomas, Daniel White

Grassroots activists across the country are working to ensure that racial justice and environmental progress go hand in hand. It’s a bitter truth that communities of color are routinely targeted to host polluting facilities in their neighborhoods and more often denied clean air and water and accessible green spaces.

We had the opportunity to speak with four inspiring individuals at the forefront of the environmental justice movement: green entrepreneurs Dior Doward, a Bronx, New York–based “ag-tivist,” and North Carolinian Daniel White, aka “the Blackalachian,” who is pushing for diversity in the outdoors industry; and two air quality advocates, Bakeyah Nelson of Houston and Taylor Thomas of Long Beach, California. Here are excerpts from those interviews.

Taylor Thomas, Long Beach, California

Research and policy analyst with the local public health activist group East Yard Communities for Environmental Justice

You grew up near the country’s two busiest container ports, the Ports of Los Angeles and Long Beach. What did your neighborhood look and sound like?

Train horns. Boat horns. Refinery flares. There was a freeway entrance next to where I had to catch the bus. It wasn’t until I got a little bit older that I started to really get a picture of, you know, this is not normal. I started to spend more time outside of my community and noticed not all the neighborhoods in Long Beach looked like mine. The sky was a little bit cleaner. Not all areas had those funky smells.

Studies have shown that the ports alone produce 100 tons of smog a day. Then there’s the air pollution coming from traffic and the many refineries and railyards in your backyard. Did that take a toll on your health?

I was diagnosed with asthma at the age of seven. That heavily impacted my ability to play because I was a really active child. I was always outside, I was always involved in sports, and I did a lot of activities with the Boys and Girls Club. So when I was diagnosed, I had to take a lot of medication, I had to go to the doctor a lot, I had to limit my outside activity or else I would end up in the hospital. It didn’t get better until I moved away for a bit.

When did you start to recognize these injustices as environmental racism?

When I started college, I wanted to be a psychologist, and that was primarily because, coming from working-class communities, a lot of us get sold the “get a good education and you’ll get out, get a nice home, a nice job,” etc. I definitely bought into that. It wasn’t until I was about 22 or 23 years old that I met someone who organized with East Yards, and they invited me out to a community meeting to learn more about what was going on here in Long Beach. [I learned] there was language and terminology behind my experiences, and a policy impact. I started to see that there could be a different purpose for me. I am thankful that I can serve a community that I was raised in. That's not something I thought I could do 10 years ago.

What kind of work do you do at East Yards?

I take the lead on a lot of our policy work; also, I kind of consider myself the in-house librarian. Our members drive our campaigns. We’re all residents here, so when we need to find out something, like how a policy or project is going to impact us, then I put in the legwork to get that done and then take that back to the members, so that they can understand the process and then give our campaigns direction. So I’m the info gatherer.

Where do you see the future of your work?

Anybody who is serious about the work will tell you that they want to organize themselves out of a job—and that would be nice. Considering how entrenched the fossil fuel industry is, how entrenched racism and capitalism are in our society, I think that it might not happen in my lifetime. I’m just really encouraged by how many folks are naming all of these systems and being courageous enough to tackle them. We are no longer accepting that we have to carry these harms and these burdens. As we’re fighting for the end of fossil fuel use, we’re seeing a big push for false solutions like credit systems and “renewable” natural gas as a fuel. Dismantling these harmful and deceptive distractions in order to get to zero emissions powered by 100 percent clean and renewable energy will be a big battle, but we’re always prepared to put everything on the line and fight for what our communities need and deserve.

Do you have a mentor at East Yards?

Evelyn Knight—she’s been involved with the organization for a while. And she was really active in the Civil Rights movement. She comes from Africatown, which was a community established by freed slaves in Alabama. I’ve learned a lot from her, not just because she’s an elder and has experienced all of these different social movements, but also because it’s hard to find elders who are also women, and especially for me as a black person. Black folks are not really visible in the environmental justice movement. Our history is important, and oftentimes as the younger generation, we don’t have the opportunity to connect with our elders in a way that is supportive or [lets us] learn and engage with each other. So I look to Evelyn for a lot of guidance and support, and she’s been really helpful in grounding me in this work and grounding me in the history of environmental justice and the history of civil rights.

Daniel White, Charlotte, North Carolina

“The Blackalachian,” outdoors ambassador

Can you describe your first experience hiking?

My first hike was kind of a spontaneous thing. I posted on Facebook one day, “I wonder if I could survive in the woods,” and my cousin responded, “Go hike the Appalachian Trail.” That was in January of 2017. On April 17 [of that year], I started my first hike.

I documented the whole experience on social media. I had to answer the question a lot on the Appalachian Trail, “Why don’t black people hike?” White people had a different connection to it. They would be planning to hike the trail for years, and I just happened to stumble upon it. There are a lot of black folks outdoors; we just don’t get enough exposure. Or people are just not looking for it enough.

Your next outdoor adventure led you to the home of Harriet Tubman. How did you choose that route?

I started to do a little research and found out about the Underground Railroad bike trail. It’s a route that goes from Mobile, Alabama, up into Canada. That was a whole different trip as far as being on the bike. A lot less weight on your back. But now you have to worry about traffic and loose dogs. It’s different from the Appalachian Trail because it’s not a bunch of established campgrounds and sites along the way. I did a lot of sleeping in cemeteries and behind churches and mausoleums—it definitely kept me on my toes. I stopped in Niagara Falls, and then I rode from there to the home of Harriet Tubman in Auburn, New York. There she had a home for the elderly, let them live their last days out, had a farm and everything. They have a museum and artifacts, including her Bible. Man, it was a serious end to the trip, definitely a culmination.

How did these hikes lead to some of your more recent adventures working with young people?

I was invited last July to come home and work with a couple of organizations in my hometown, Asheville, North Carolina. Organizations like Conserving Carolina, Asheville Greenworks, Southern Appalachian Highlands Conservancy, and Appalachian Trail Conservancy invited me to come speak and do a couple of hikes with the kids. I got to speak to the summer camp youth at Shiloh, the recreation center I grew up in. That was pretty cool. Trying to get these kids outdoors is my goal now. I have some events coming up in Asheville in March and April, a couple of block parties for the kids. I want to do a couple of bike rides for the kids, so we are in the process of trying to get some bikes donated so we have enough for them to ride.

What’s your biggest message to black kids that grow up without a connection to nature?

They don’t feel it, but it's there. It’s an innate thing. And you don’t even realize it. Being out on the Appalachian Trail for so long, you tap back into that. You smell things a little bit differently, you see things differently, you can read the weather a little better—because you are getting back in tune with who you really are. So it’s in them; they just aren’t aware of it. But I understand why. There’s a lot of factors that go into why. A lot of black kids aren’t able to just get out and enjoy the outdoors. Between home life and the system that’s in place, not all of those things add up. My biggest message would be to speak to the older folks and say that it’s on them to get the youth out there. I am also trying to give the youth some awareness that this outdoor community is huge. I want to show them you can do outdoor jobs and make a decent living. It’s a billion-dollar industry, and these kids need to know that. They may think that they can only make money off of rap and sports, and that’s cool too, but everybody ain’t Wayne, everybody ain’t Kendrick Lamar, and everybody ain’t LeBron. My message would be to try and find a different way. Step outside the box.

Bakeyah Nelson, Houston, Texas

Director of the clean air advocacy group Air Alliance Houston

How did you start working in the field of environmental justice?

About 10 years ago, I moved with my family from Maryland to Houston and began working at Harris County Public Health. We got a grant for an environmental equity project and started working with the community of Galena Park. It’s a town right outside Houston and right along the Houston Ship Channel.

The channel is about 50 miles long and has more than 400 facilities, and Galena Park is one community that sits directly adjacent to it. When I visited for the first time, I had never seen people living so close to facilities that could explode at any time and were releasing air pollutants [such as benzene, a known carcinogen, and fine particulate matter] that were damaging the health of the community and the environment. It was a really overwhelming experience for me.

The structure of the initiative was community led, meaning that in our role, we were just there to listen and facilitate. A lot of my work was relationship building with residents in the community. It became my second home for a couple of years.

Galena Park is one of many low-income communities of color in the Houston area that are fighting against a legacy of environmental injustice. Others are surrounded by concrete batch plants, for example. How did conditions like these become so widespread?

When you think about the history of Houston, and when you look at where people live, the environmental justice issues stem from a legacy of segregation. This legacy of segregation was facilitated by unfair governmental policies, housing policies, infrastructure, and the ways that highways divided communities. The outcomes that we see today, or the design of communities, or where things are sited, is left over and from a time when communities were intentionally segregated. Some would argue that they continue to be intentionally segregated.

It’s much easier to get away with siting toxic facilities in communities of color and low-income communities that are segregated because often you don’t have the same leverage, political clout, or resources to fight against it. It’s much easier to continue this legacy of putting hazardous facilities in these communities because policies and practices have perpetuated segregation between people of color and white people, and affluent versus low-income people. Additionally, the air permitting process in Texas does not consider the cumulative impacts of having a concentration of polluting facilities in close proximity to each other. The presence of existing facilities is not considered, and that is a significant problem.

As a person of color, have you found that being an executive director of an environmental nonprofit presents any challenges?

I probably face fewer obstacles today than when I first started in my position two years ago. When I started, I got a lot of surprised looks when I was being introduced. Sometimes there were questions of my credibility, like “What’s your degree in?” Sometimes I’d try not to have a knee-jerk reaction like “You’re only asking me that because of who I am and what I look like.”

Over time there’s always that additional burden of feeling enormous pressure to perform and exceed expectations—and to work extremely hard so that I don’t fail or I don’t mess up. I am humbled by the whole experience in general. I have many communities relying on me and our organization and working in partnership with us to try to address longstanding environmental justice issues. That in itself is very humbling.

How do you describe your work to your three children?

Back when I was working in Galena Park, my oldest was 10 years old and her brother was 8. I took them with me [to work] one day and the first thing that my son said when we turned down Clinton Drive was “Mommy, why is there smoke coming out of the buildings?” It never occurred to me, which is kind of silly now that I think about it, that he would be so perplexed as to why there were buildings with fire and smoke coming out of them. It was abnormal to him. It really struck me in that moment how abnormal it is to have people living so close to those types of facilities. The innocence of a child recognizing that “something is wrong with this picture” was a powerful moment for me, a reminder that I was engaged in work that was meaningful.

I still talk to them a lot about the work that I do. I take phone calls with them in the car, when I’m talking to residents, so that they can hear my exchange and they can learn about the desperate situations people are facing. I try not to preach, but I try to expose.

Dior Doward, Bronx, New York

Founder of the composting collective and sustainability advocacy group Green Feen

Can you introduce yourself by sharing one of the raps you perform to talk about sustainability in the Bronx?

Sure! I usually do this one when I’m talking about waste equity.

Okay

Welcome to my town

The Boogie Down Bronx

Home of the green and brown

My roots so thick

From the soil to the tip

Of my hair getting air

No anaerobics

Only organic if I can help it

But I’m not buying if you FDA sellin’

I’m not for the profit

I’m just for the people

And waste equity got lots to do with being equal

SO tune in for the now

And tune in for the sequel

’Cause this black and gold proud

And proven

To be lethal

Thank you! So, now tell us: How do you combine your work as a certified master composter with your hip-hop and your waste equity business, Green Feen?

Green Feen is essentially an environmental consulting firm, and we use hip-hop to teach sustainability through compost education and renewable energy. Traditionally and historically, it’s just been me going into these spaces, places, and organizations and using hip-hop. A lot of times I like to freestyle about what is happening in the moment. I’ll freestyle at community boards to give my presentation about what’s happening, bring people in. Or I’ll go into schools and we have writing activities, or I’ve had summer youth and we’ll do Rhyme for the Time.

Then we have Green Feen Organics [a separate, for-profit branch of Green Feen]; it’s a waste management company. What we do there is we collect organics locally to be processed locally to ignite community-based solutions that promote waste equity within the South Bronx. That one has a little bit more of a political education aspect. We are a worker-owned cooperative, because we are trying to recognize that one of the ways in which we develop agency for ourselves is by being able to take care of ourselves.

You got your start in urban farming through an experience as an apprentice with Soul Fire Farm, a CSA-only family farm focusing on environmental justice in Albany, New York. What did you take away from the experience?

I was so blown away by Soul Fire Farm’s mission, by what they stood for, about what they were trying to accomplish, especially as it pertains to people of color and our relationship with the land. Part of my inspiration for doing Green Feen was this idea that I felt like, wow, they are doing a great job of tackling this idea of farm to table, but what are we doing about table back to farm? There is a large disconnect. We talk so much about healthy eating, and sustainability, and local produce. But what are we talking about as it relates to how we are handling our waste? That is just as important in the conversation. Mind you, I know that it’s not sexy and attractive, which is one of the reasons why I bring the element that I bring to the conversation. Because I want it to be light, I want it to be fun, I want it to be attractive, I want you to want to engage with it.

Why is it important for you to do this work in the Bronx, where you grew up?

There is a reason why we try to take responsibility and say, “Where the waste is created is where it needs to be processed and handled.” We as a borough don’t deserve the entire city’s trash, and we recognize why we do have it. Historically, this has just been the practice of large businesses. And we are deciding that today it is going to look different.

I have a duty, as someone who is from this borough, to make sure not only that I give back to it, but that I’m able to show the rest of these young kids coming up that you just follow your dreams, your inspirations, and your passion to bring you the things that you want. But you also pay homage to where it is that you come from, because it helps to shape you.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

In Planning for Climate Change, Native Americans Draw on the Past

The Particulars of PM 2.5

What Is the Justice40 Initiative?