Shared Knowledge Is Power in the Northern Mariana Islands

As Indigenous groups seek to comanage the Marianas Trench Marine National Monument, elders help the next generation find opportunity on the islands in science and conservation.

Jellyfish seen during Dive 4 of the Deepwater Exploration of the Marianas expedition on April 24, 2016. Scientists identified this species as belonging to the genus Crossata.

NOAA

The lowest point on earth lies within a crack in the ocean floor that’s roughly the shape of a crescent moon. Stretching 43 miles wide and reaching 36,000 feet below sea level, the Mariana Trench is home to wildlife and habitats found nowhere else. With its unique geology of hydrothermal vents, cold seeps, and submarine mud volcanoes, the trench supports some of the earliest known forms of microbial life as well as deep-sea oddities like dumbo octopuses, snailfish, fangtooths, black sea devils, goblin sharks, and vampire squid. While much of the trench remains unexplored, researchers have found a plastic bag at the very bottom—a disheartening realization that humanity’s ever-growing waste stream sullies even the planet’s deepest and darkest places.

Up on the surface and to the west lie the Northern Mariana Islands, a U.S. commonwealth consisting of 14 islands within an archipelago anchored by Guam, a U.S. territory, to the south. Indigenous people have been stewards of this corner of the Pacific Ocean for thousands of years. Despite colonial powers carrying out forced relocations and significant disruptions to their ways of life over the past 400 years, the islands’ two largest Indigenous groups—the Chamorros and the Carolinians—have passed down many of their maritime customs, such as traditional ways of fishing and canoe building, from generation to generation. Today, that relationship to the water is as important as ever as climate change threatens their shores and as the people of the Marianas face socioeconomic challenges, including sparse job opportunities and climbing costs of living.

“Just like any Pacific island, we struggle with capacity,” says local advocate Sheila Babauta. “People leave to pursue higher education or job opportunities that just aren’t available here. And very few return.”

Babauta did return. After nearly 10 years of studying and working abroad, she came back to the Marianas and served two terms as the youngest representative in the 21st and 22nd Northern Marianas Commonwealth Legislature, and she joined the Obama Foundation’s Leaders: Asia-Pacific program. Now, she’s part of a movement to grow opportunities for the islands’ youth through science, culture, and conservation.

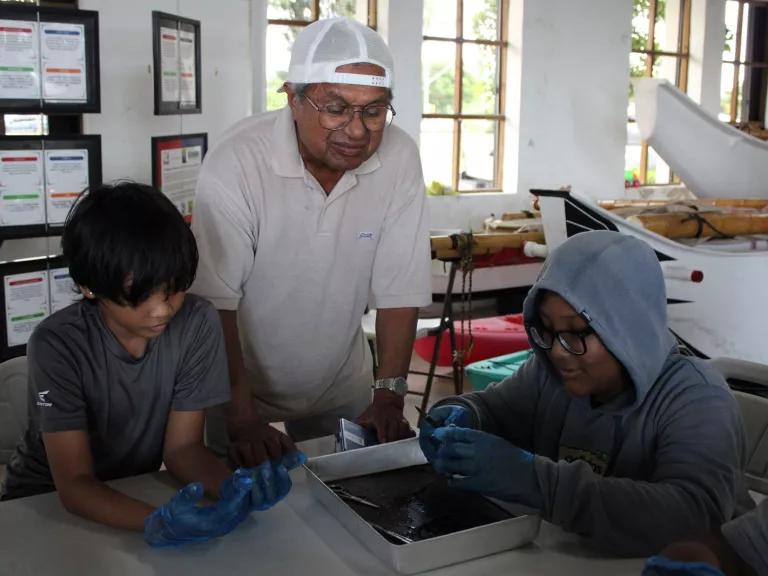

Ramon Rechebei, an ocean elder with Project HOPE, shares knowledge with Indigenous youth as they dissect a sea creature.

Courtesy of Friends of the Mariana Trench

A cycle of stewardship

The Chamorro creation story begins with a sister and brother, the gods Fu’una and Puntan. After Puntan dies, Fu’una takes his body and gives it life. His eyes become the moon and sun, and his brows refract the light into rainbows. His back becomes the land she tills, and the rhythm of his heartbeat paces the turning of day into night into day. Lonely, Fu’una transforms herself into Fouha Rock and lets the waves crash into her. The sea breaks her into bits of sand and carries them off to become the people of the world that Fu’una created.

That inextricable bond between the earth and its people is what Friends of the Mariana Trench (FOMT), a local nonprofit that advocates for policies that promote conservation and cultural preservation, hopes to kindle in the islands’ young people. Its Project HOPE, which stands for Healthy Oceans & People Empowerment, provides a place for middle schoolers to learn firsthand from Indigenous elders about ocean conservation and watershed management, and to meet college students pursuing degrees in the sciences.

During her first term in the legislature, Babauta first learned of FOMT after her office adopted a youth center in Tanapag—one of the most rural and traditional villages in Saipan, the commonwealth’s largest island. Some of the center’s children had signed up for Project HOPE, but they had no way of getting to the meetings on the other side of the island. Babauta, who has since become chairwoman of the group’s board, volunteered to rent a van and drive them herself.

Participants of the program, now in its fifth year, meet in the village of Susupe at Guma Sakman, a warehouse-style facility that houses canoes crafted by community members. There, the kids listen to guest speakers, spend one-on-one time with the elders, and talk to students attending the nearby Northern Marianas College about potential future career paths involving conservation. Project HOPE intentionally keeps the learning local—having elders pass on their knowledge of conservation and nature helps preserve their legacy and ideally encourages a cycle of teaching between generations within the community. Some days, the students learn about coral reefs and some days they dissect sea urchins, but every session ends with a communal beach cleanup and a dip in the ocean.

The Mariana Trench is located east of the Mariana Islands and Guam in the Pacific Ocean.

Getty Images

A monumental opportunity?

Designated in 2009, the Marianas Trench Marine National Monument stretches more than 95,000 square miles. Along with the trench itself, the monument protects 18 underwater volcanoes and thermal vents as well as the waters and submerged lands of the Marianas’ northernmost islands—Asuncion, Maug, and Farallon de Pajaros—all of which are volcanic, uninhabited, and crucial breeding grounds for some of the region’s rarest birds.

While the people of the Marianas appreciate the sentiment behind the monument, many have been hesitant to embrace the designation. “There is interest in conservation. There is interest in protecting our resources. Interest in the monument? That’s a whole other story,” says Babauta. She explains that there has been a lack of transparency on the part of the government, and that at first, many people simply did not know what a marine national monument entailed. “There were also concerns about a federal takeover of our waters,” she adds. Such distrust is understandable in a place that has been governed by four different outside nations—Germany, Japan, Spain, and the United States—in just the past 150 years. The fact that the monument’s management plan sat in limbo for more than a decade after its proposal certainly didn’t help matters.

The main concern for Marianas residents is whether they will have a say in the running of the monument. “We want to be involved, to offer training, and to bring resources into our communities. But we want to do it in a way that is appropriate for our people,” says Babauta.

". . .opportunities that encourage understanding and conversation about what kind of place we are and what kind of place we dream to be."

Sheila Babauta

To that end, the tide seems to be turning in a positive direction. Currently underway in the American West is the comanagement of another national monument between the federal government and Indigenous groups: Released last October, the new management plan for the Bears Ears National Monument in Utah aims to employ a full-time tribal staff to oversee the monument alongside federal employees; establish and fund a traditional knowledge institute; and develop equity bylaws that will help ensure the partnership continues over time. In the Marianas, advocates hope a similar partnership is taking shape.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service (FWS) finally released the draft management plan for the Marianas monument in 2020. In addition to environmental education, tourism opportunities, and marine conservation, exploration, and research, the draft plan includes cultural and heritage protection among its goals and ensures access for Indigenous fishing activities. FOMT, which has been pushing for the monument since 2008, is overall supportive of the plan but still had a lot to say during the public comment period. First, the group noted that the lateness of the draft plan should not further delay its implementation. The group also requested translations of all management documents into Chamorro and Carolinian; more frequent opportunities created by the agencies for public input; and the incorporation of traditional knowledge into the plan to be a higher priority. The FWS stationed a liaison on Saipan in 2021 to help foster communication between the local communities and the federal officials working on the monument, but a final management plan has yet to be issued.

Saipan, Northern Mariana

Zhao Liu/Getty Images

A culture of science

In its recommendations to NOAA and FWS, FOMT also included policies to protect against “parachute science,” aka “colonial science.” The terms describe circumstances in which scientists from richer nations, or those financially backed by wealthy institutions, come to research an area, but once they publish their studies, they leave without providing further investment in or sharing any knowledge gained with local communities. This almost parasitic relationship can not only ignore Indigenous wisdom regarding the local environment but can also potentially impede local scientific efforts and lead to a dependency on external sources for funding and innovation.

“Despite several dozen expeditions to the bottom of the Mariana Trench, no Indigenous Chamorro or Carolinian explorers or scientists have been part of recent dives,” states FOMT, which advises that local researchers and cultural experts be involved at every phase of the research projects being conducted at the trench, from planning to sharing the results. This would include an onboard observation program to monitor a vessel’s activities within the monument and, possibly, researchers inviting local students and teachers to accompany them on trips into the field.

As the monument plan slowly progresses—and so far, without any updates from the agencies on implementation—FOMT is working to expand its educational outreach by establishing ocean clubs in the public high school system. As club advisors, adults trained in ocean stewardship leadership will guide students while they complete projects around natural resource management policy and ponder their future careers.

“If there are opportunities that encourage understanding and conversation about what kind of place we are and what kind of place we dream to be,” says Babauta, then instead of emigrating from the islands, “people might be more inclined to come back and contribute.” And perhaps one day, it will be a local scientist making a breakthrough discovery in the Marianas.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

These Photographs Show How the Rising Sea Connects Us All

A Race to Track the Southern Seas

Climate Tipping Points Are Closer Than Once Thought