Mobilizing Equity, Implementation & Ambition at COP27

As countries gather in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt for COP27 (the 27th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the international climate convention) they need to mobilize key actions to ensure that the global response to climate change is more equitable, fully implemented, and ambitious enough to hold temperatures to 1.5°C.

Women carry belongings salvaged from their flooded home after monsoon rains in Pakistan, Sept. 6, 2022..

As countries gather in Sharm El-Sheikh, Egypt for COP27 they need to mobilize key actions to ensure that the global response to climate change is more equitable, fully implemented, and ambitious enough to hold temperatures to 1.5°C.

They can do this by delivering several key actions at COP27 (the 27th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the international climate convention) and marshaling even more in the months following the summit in Egypt.

Turning Emissions Cutting Promises into Action…and Delivering More Ambition

We left the last climate summit in Glasgow – COP26 – with a promise. If we delivered all the commitments from countries, companies, investors, and key sectors we could be on a trajectory to hold temperatures to 1.8°C. That is a significant improvement from the 2.9°C trajectory we were headed towards prior to the Paris Agreement. But that trajectory was only possible if all these decision-makers turned these promises into action. The atmosphere doesn’t care what you pledge, only what you deliver. The meeting in Sharm El-Sheikh needs to show significant delivery of those promises and clear steps to ensure they occur no later than 2030. A recent report from leading researchers shows that the world hasn’t yet delivered, concluding: “none of the 40 indicators of progress spanning the highest-emitting systems, carbon removal, and climate finance are on track to achieve 1.5°C-aligned targets for 2030”.

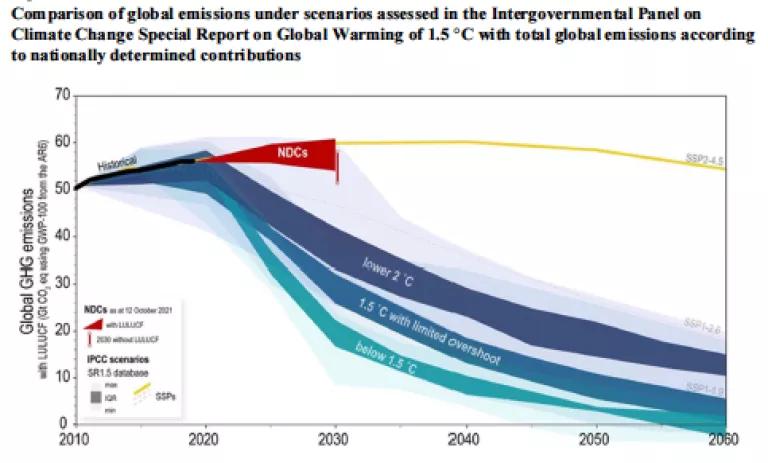

But we also left COP26 with a need for more action to deliver on the full promise of the Paris Agreement. Unfortunately, the picture hasn’t gotten much better since Glasgow. National country targets – Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) – formalized to date would result in global emissions 16 percent above 2010 levels, as compared to the 45 below required to be on a 1.5°C consistent path by 2030. According to the UNEP “Gap Report”, the delivery of “unconditional NDCs” would leave us with a 23 GtCO2e emission gap in 2030, with the gap shrinking to 20 GtCO2e under the NDCs levels delivered with “conditional” international support. And the situation will be even worse if countries don’t take more action domestically since current policies would leave an emissions gap of 25 GtCO2e.

So, we need to fully implement the existing commitments and deliver greater ambition if we are to uphold the full promise of the Paris Agreement.

Addressing the Impacts that Can’t Be Adapted To: Loss and Damage

It is critical that the U.S., E.U., and other developed countries make clear to vulnerable countries that they recognize the importance of mobilizing resources to address loss and damage. There are real impacts that are already occurring at 1.2°C; and these will worsen – even if we succeed in holding temperatures to 1.5°C. As climate impacts mount globally, they are also outstripping the ability of many communities – particularly the poorest and most vulnerable – to cope. For example, no amount of adaptation could have prevented the major loss of crops and destruction from the climate catastrophe of the recent flooding in Pakistan. You can already see this in the economic development data, with the fifty-five most climate-vulnerable countries having lost about one-fifth of their GDP over the last two decades due to climate impacts. At COP27 countries need to stand-up the existing mechanisms including the Santiago Network for Loss and Damage and begin to deliver two financing strategies that begin to address the losses and damages from climate change.

Agreeing on a financial arrangement under the UNFCCC. We need the U.S. and other developed countries to agree to specific funding arrangements to address loss and damage by the end of COP27. The U.S. and other developed countries must be flexible and creative, but we can’t leave Sharm El-Sheikh without a clear path on tools to mobilize finance for this critical issue. Countries should explore existing institutions and mechanisms, as well as new pathways to deliver support to vulnerable countries that contributed the least to climate change but are suffering unavoidable harm from its impacts.

Mobilizing the full suite of finance. Both at COP27 and next year, the developed countries need to mobilize funding through a variety of mechanisms. For example, developing countries have significant debt challenges tied to losses and damages that can be addressed through debt relief measures. The multilateral development banks (MDBs) – such as the World Bank – and multilateral climate funds must accelerate the speed of resource disbursement following a disaster. And other existing funding mechanisms must be better equipped and if necessary adapted to effectively address loss and damage.

Mobilizing More Climate Finance

To meet the Paris goals of keeping global temperature rise to 1.5 degrees Celsius and ensuring countries and communities are resilient to the impacts of a warming world, there is a need for significantly scaled up climate finance. In 2020, total global climate finance was $640 billion, but needs to reach over $5 trillion per year by 2030, more than an eight-fold increase. There are several fronts on which COP27 can advance progress on climate finance.

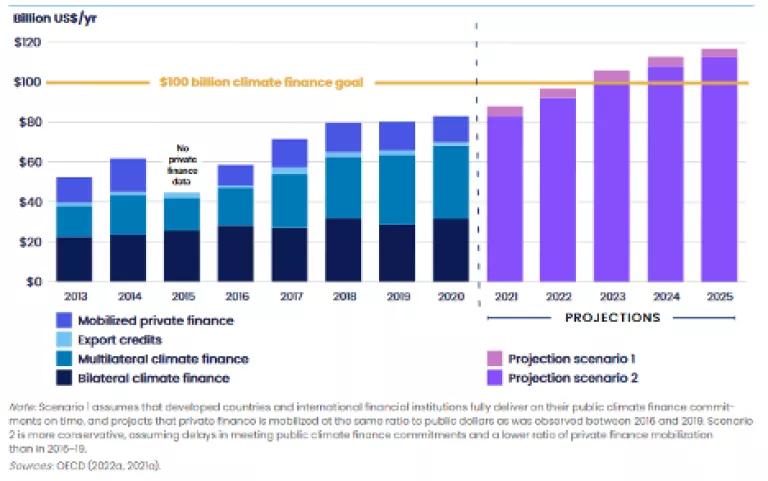

Delivering on the $100 billion per year target. Developed countries must provide reassurance that they will finally deliver on their commitment to mobilize $100 billion a year in climate finance to developing countries. This funding is a vital lifeline for countries struggling to adapt to increasingly severe climate impacts and invest in a just transition to clean economies. The goal was first set in 2009 and was due in 2020, but developed countries fell $17 billion short. The continued failure to meet the $100 billion commitment has severely undermined trust between countries in the UN climate negotiations. Developed countries have projected that they will deliver on the $100 billion by 2023 (see figure). While past failures cannot be undone, developed countries should aim to exceed $100 billion in 2023, 2024 and 2025, so that their contributions across the period 2020 to 2025 average at least $100 billion a year. To do this, they must reaffirm their post-2020 climate finance pledges and provide more detail on what they will each be contributing.

Annual reported climate finance (2013–20) and projections (2021–25) toward the $100 billion goal

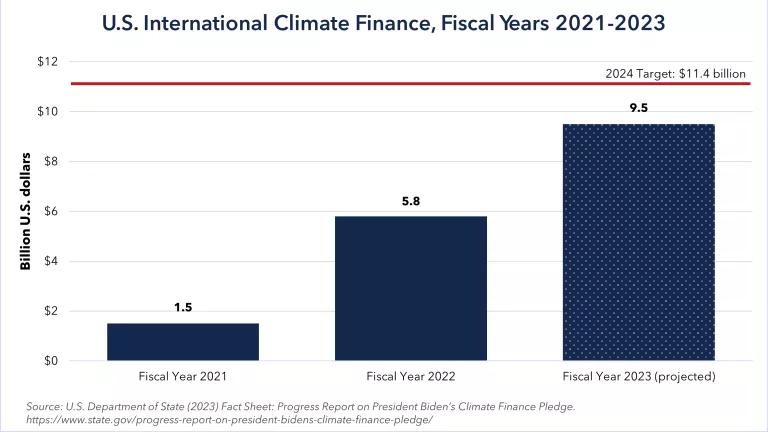

Coming out of COP27, the Congressional appropriations negotiations in December represent a can’t-miss opportunity for the U.S. to raise the floor of its public climate finance. A broad coalition of development, faith-based, environment, health, foreign policy, and business organizations are urging Congressional and Administration leadership to prioritize securing $6.7 billion in direct climate finance for fiscal year 2023, as part of a wider effort to get as close as possible this year to President Biden’s $11.4 billion per year commitment. Alongside increased contributions that other developed countries have pledged, this could finally close the gap to the $100 billion.

Doubling adaptation finance. Adaptation made up only 24 percent of overall climate finance from developed to developing countries between 2016 to 2020, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and only 37 percent of their public financing was in the form of grants. The Paris Agreement calls for climate finance to be balanced between mitigation and adaptation, and there is a need for significantly higher level of grants than loans for adaptation, since poor countries should not have to go into debt to deal with a problem they did little to cause.

At COP26, developed countries committed to at least double their adaptation finance from 2019 levels by 2025. Based on OECD data, this would be an increase from $20 billion to $40 billion. Developing countries are rightly skeptical that this new pledge could see a repeat of the failed $100 billion commitment, and developed countries need to show that this time things will be different. Several countries and multilateral development banks have yet to make adaptation finance commitments and should do so urgently. One way to build confidence that adaptation funding will indeed grow as needed would be to make new pledges to multilateral adaptation-focused funds such as the Adaptation Fund and Least Developed Countries Fund. They have proven track records in rapidly delivering grant-based funding to vulnerable countries.

Refreshing the World Bank Group. Countries should commit to reforms that enable the MDBs to scale up their climate finance and expand their overall lending capacity. The World Bank Group alone could increase climate finance by $13 billion per year if it increased its climate finance target from 35% to 50% of its overall spending. And these investments could grow even higher if the MDBs took more of their current capital and turned it into financing for developing countries as called for in the Capital Adequacy Framework (CAF) review. We and our partners have recommended five reforms that could significantly increase the World Bank Group’s investment and action to address climate change.

Finding innovative tools to spur more finance. Developed countries should announce innovative measures to increase climate finance and create fiscal space for developing countries to invest more in climate strategies. This could include using sovereign guarantees for the Just Energy Transition Partnerships, commitments to channel their Special Drawing Rights to the IMF’s Resilience and Sustainability Trust, pioneering debt-for-climate swaps, and supporting the establishment of “green banks” or similar local, mission-driven climate finance institutions or facilities.

Local climate finance institutions can play an essential role in facilitating and speeding up the transition to low-carbon and resilient infrastructure in developing countries by helping to build project pipelines, structure transactions, and mitigate risks. They can serve as a conduit for local and international public capital and mobilize additional domestic and international private capital by providing catalytic, innovative finance and risk-sharing mechanisms. They can also help shift the local investment climate, inform changes to the enabling policy environment, and launch local green markets by building capacity across stakeholders, including public agencies, commercial banks, and project developers.

More Ambition from Key Countries

Under the Glasgow Agreement, countries agreed to “revisit and strengthen” their 2030 national climate targets by the end of 2022. Only 24 countries recorded new or updated national climate plans. And there is still a significant gap between the national climate targets, the domestic implementation to date, and the level of action by 2030 necessary to put the world on a 1.5°C aligned trajectory (see figure). So, we need countries to significantly step-up their action in this decisive decade. Here are some signs of the key directions in the coming months.

U.S. needs to effectively implement their climate law and deliver more action. With passage of the Inflation Reduction Act – aka the “U.S. Climate Law of 2022” – the U.S. has the potential to cut its climate pollution by 40 percent by 2030 (from 2005 peak levels). Further steps will be needed by the Biden Administration to fully meet U.S. target to cut climate pollution by 50 to 52 percent by 2030.

E.U. is working to deliver its Green Deal and signaled it can strengthen its target. The E.U. is moving through making “Fit for 55” law – its target to cut emissions 55 percent below 1990 levels by 2030. The E.U. has agreed 2030 emissions targets for new cars and vans and set a target that all new cars and vans will have to zero emissions by 2035. And they are working to finalize the other important changes to their laws to be able to deliver on the 55 percent cut target. E.U. countries have signaled that they will strengthen their target next year.

India will exceed its Paris Agreement targets given its massive deployment of renewable energy, new laws on energy efficiency, and focus on other key near-term actions. India will meet its 175 Gigawatt (GW) target for wind and solar about 6 months after its original goal of the end of 2022, but this was unthinkable even a few short years ago and will be delivered despite the slowdown in development and investment during the pandemic. And as India drives forward with more renewable energy deployment there are strong signs that India will be able to meet its 50 percent non-fossil energy capacity target by 2030. It will not be easy, but the country is focused on delivering this target by mobilizing the policy reforms and finance necessary to deliver. India will also play a critical role next year in helping to advance climate action as the host of the G20 which will be a key forum to advance implementation coming out of COP27.

China can peak its CO2 emissions before 2030 and at a meaningfully low level as indicated by several factors. First, provincial-level renewable energy targets through 2025 would significantly exceed the national wind and solar energy target set for 2030 of 1,200 GW – China could meet that national target 5 years earlier (with over 1,500 GW by 2025) as it has consistently done with previous renewable energy targets. Second, electric vehicles deployment is growing rapidly in China and this could lead to an oil consumption peak much earlier than many envisioned even several years ago. Third, many of China’s most coal and carbon-intensive sectors have already or will soon peak their CO2 emissions. NRDC-supported research on 4 key sectors – power, iron and steel, cement and coal chemicals – found that the combined coal consumption and carbon emissions from these 4 sectors could peak by 2025. These four sectors together comprised 72% of China’s carbon emissions in 2019.

Turning Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETP) into action. The G7 countries are working to finalize energy transition packages with a handful of countries to speed-up the early retirement of existing coal and gas infrastructure. In South Africa, they need to deliver an investment plan that sets out the clear finance trajectory necessary to deliver on South Africa’s 1.5°C aligned coal transition, begin to mobilize the necessary finance to deliver on the pledge of $8.5 billion from key developed countries (i.e., one part of the package is beginning to move), build more political support in-country for a durable transition, and develop innovative finance to fill the expected finance gap. For Indonesia, it needs to ensure that the exact trajectory of the coal transition as Indonesia has just approved a massive new coal plant which is putting at risk the JETP. And the Indonesia JETP must develop an investment package that is attractive in mobilizing Indonesia to a 1.5°C aligned trajectory by 2030 for its energy sector. For Vietnam, the JETP needs to ensure that the energy transition clearly moves away from coal and other fossils since Vietnam’s current draft of its energy plan – Power Development Plan 8 – isn’t yet in line with a 1.5°C trajectory. The country also needs to release the four climate experts that are in jail for dubious tax reasons as the transition will not be durable or effective with the current situation continuing.

Powering Africa with clean. African countries need support to bypass traditional fuels and infrastructure and go straight to building sustainable, renewables-based energy systems, but they will need the international community to step up, especially to attract the necessary investments. Many African nations have a grave need for strengthened international cooperation for addressing existing barriers to clean energy investment and to accelerate the deployment of adequate volumes of fresh capital across the continent. At COP27, leaders need to show that they support Africa’s efforts at achieving 100% energy access and building the required infrastructure for rapidly scaling up renewable energy capacity. Sharm-el-Sheikh will provide an important opportunity for commencing implementable actions in 2023 to deliver that goal.

Deploy renewable energy faster. The prospect of new coal-fired plants being built in most countries is very unlikely given the financing challenges and the lower cost of building renewable energy alternatives. We need countries to reaffirm their commitment not to finance new coal-fired power plants, deliver tools to retire older capacity, along with the global private financial institutions reaffirming the commitment to accelerating the net-zero transition. We need a global push to help build the 1,200 GW of wind and solar that the world needs annually through 2030 to deliver on our 1.5°C target. Countries can begin to deliver on this by bringing forward new innovative financing tools that use limited public dollars to crowd-in private finance to invest in the actual pipeline of projects. This could include the multilateral development banks making sure to deploy capital for increasing their portfolio of large-scale renewable energy projects, building energy storage, and expanding electricity grids to integrate more variable renewable energy generation. They can also mobilize more wind and solar by delivering renewable energy as the cornerstone of the JETP transitions and deploying large scale renewable energy transition strategies for all the other countries. This could include using innovative finance strategies (e.g., foreign exchange hedging, green banks, and blended finance), investments in key infrastructure such as renewable energy grids, and massively ramping-up renewable energy manufacturing to meet the 1,000+ gigawatt scale per year deployment.

Laggard countries such as Mexico and Brazil need to reboot their climate policies. There is a potential turning point in Mexico as just days before the start of the COP, Mexico indicated its commitment to reduce its greenhouse gas emissions by 30 percent by 2030, an increase from the previous target of 22 percent. Announced during John Kerry’s fifth visit to Mexico in a year, the target may indicate new openness by President López Obrador to accelerate action on climate change. During the visit, Mexico also highlighted additional steps it is taking, including PEMEX’ pledge to capture 98 percent of methane emissions and the Sonora Plan which focuses on solar energy, lithium, and semiconductors in a bid to turn the state into an electric vehicle hub. But actions speak louder than words. In the past three years, Mexico has taken a steady stream of actions to weaken the renewable energy sector, unfairly bolster its fossil fuel industry, and deprioritize climate action. Mexico’s actions against the renewable energy industry –including U.S. firms– contributed to the U.S. calling for consultations under the U.S.-Mexico Canada Agreement (USMCA). At this point, more than pledges and plans are necessary to turn Mexico into a climate leader.

A political shift in Brazil could turn the tide in Brazilian Amazon as President-elect Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva has pledged to prioritize climate action and end deforestation, signaling a shifting tide in Brazil. During his previous two terms as president (2003-2010) Lula da Silva enacted policies to protect the Amazon and Brazil saw deforestation rates drop by over 70 percent. This trend was rapidly reversed under President Bolsonaro who dismantled environmental protections, legitimized illegal activity, and supported policies that opened the Amazon to large scale mining, oil and gas extraction and other destructive activities. Lula will need to rebuild environmental agencies, strengthen protection of indigenous peoples and environmental defenders, and immediately start enforcing existing forest protection laws. According to an analysis by Carbon Brief, full implementation of the Forest Code could result in deforestation dropping by 89 percent by 2030.

Addressing Canada’s climate liability. As a new report from NRDC and Nature Canada shows that, based on the Government of Canada’s own data, the logging industry is responsible for more than 10% of Canada’s total annual greenhouse gas emissions. Each year, the logging industry clearcuts more than 550,000 hectares of forests in Canada, equivalent to six NHL hockey rink-sized areas every minute, with a climate impact on par with tar sands production emissions. The pace of these industrial logging operations has led Canada to lose its carbon rich and biodiverse intact forests, at a rate just behind that of Brazil. The integrity of Canada’s climate plan, as well as its commitment under the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use, depends on a full, accurate, and transparent accounting of all major sectors, including logging, and a strategy to reduce the logging industry’s emissions in alignment with its broader 2030 climate commitments.

Climate Equity, Implementation, and Ambition Can Be Delivered with the Right Tools

Leaders have a responsibility and opportunity at COP27 in Egypt to help continue to accelerate the global response to climate change. They can do this by ensuring that the outcome delivers more equity, implementation, and ambition. They can deliver more equity by addressing loss and damage finance, mobilizing more climate finance for developing countries, ramping up support for adaptation, and delivering more emissions reductions so the most vulnerable face lessened climate devastation. Leaders can help shepherd more implementation by making sure that the promises are turned into real action and that there is no backsliding that makes 1.5°C even harder to reach. And they can help rally around greater ambition to ensure that the world is on a clear trajectory by 2030 to ensure that we hold temperatures to 1.5°C and minimize the climate devastation that hits the most vulnerable the hardest.