The Canal: Underserved Community Organizes for Climate Justice

Below the hills of Marin County, residents in the shoreline Canal district build toward climate resilience through community-led sea level rise adaptation.

Jean and John Starkweather Shoreline Park

Jocelyn Rojas

This blog was written by Jocelyn Rojas, NRDC 2023 summer intern. Support for this internship program is provided by the U.C. Merced Division of Equity, Justice, and Inclusive Excellence.

Ironically, the streets in my barrio are named after the wealthy cities and towns surrounding us. Fairfax, Novato, Sonoma, and Larkspur have houses priced far above a million dollars. However, in the Canal district of San Rafael, California, day laborers and multi-family renters crowd into run-down apartments on Sonoma Street.

I, along with generations of Canal residents, grew up walking along the shoreline that outlines our neighborhood. The marshland ecosystem contouring the shores of Canal is one of the few natural spaces readily accessible to my community, despite being surrounded by vast oak woodlands and mixed evergreen forests. Every evening after school and work, families walk and ride their bikes along this path, chat with distant relatives on the phone, and fish. During the peak of the global pandemic, the shoreline provided solace. Now, global climate change is forcing us to adjust how we live our day-to-day lives.

View from Jean and John Starkweather Shoreline Park.

Jocelyn Rojas

Shorelines and Communities at Risk

Some of California's most vulnerable populations are bordered by the sea. Many cities are now developing strategies to combat the effects of rising tides threatening the almost 40% of the U.S. population living along the coast. Community-driven climate adaptation projects are underway in neighborhoods on the frontlines of climate change. Even so, water does not rise equally and communities living along the shore are not impacted in the same ways or to the same extent.

Climate Justice in Canal

Located within Marin County, in between the Golden Gate Bridge and Sonoma County vineyards, the district of Canal remains one of the most segregated neighborhoods in the Bay Area. Over 90% of my community is made up of immigrants from Mexico, Guatemala, and Vietnam, in contrast with 66% of the Marin population who identify as white.

The Canal is situated between the San Rafael Bay, a polluted waterway, and the 101 freeway. Systemic racism and oppression made it so that immigrant communities could not build wealth, become homeowners, or live anywhere outside of the Canal.

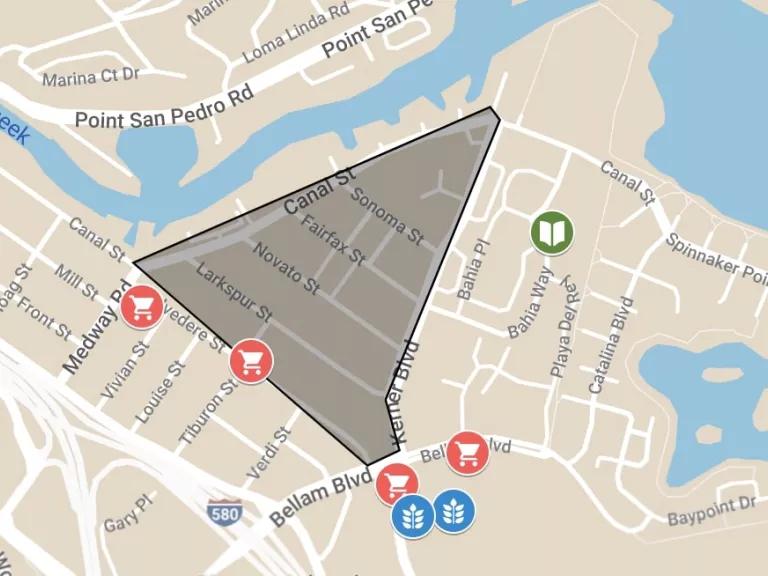

By the end of the century, the Canal neighborhood—one of the most densely populated areas along the San Rafael shoreline—could flood daily. Healthcare and wellness buildings, culturally relevant grocery stores, schools, and some of the last low-income housing units left in Marin County would be impacted. Displacement concerns are already prominent within the Canal neighborhood due to rising rent prices and a lack of affordable housing. Now, rising tides are poised to exacerbate these fears.

Map of health and wellness buildings, an elementary school, and grocery stores in Canal

To address community concerns, local and countywide organizations and government partners have jointly developed the Canal Community Resilience Planning Project to address short- and long-term climate change-related flood risks in Canal.

This partnership includes Canal Alliance, The Multicultural Center of Marin, Marin County, and researchers at the University of California, Berkeley. This coalition received funding from the California State Coastal Conservancy and the Marin Community Foundation to conduct an equity-guided study to assess the feasibility of climate change adaptation projects within the Canal neighborhood.

Canal Alliance has been serving the community directly for years, providing social services and legal assistance to residents. This grant would increase capacity within community-based organizations, including Canal Alliance, to be able to lead community advocacy training and compensate Canal residents for their input and participation. This relationship may also help establish trust between government partners and impacted communities.

In the proposal, project partners highlight the importance of local community input to develop equitable and inclusive adaptation projects to overcome racial, social, and economic barriers that have hindered the engagement of underrepresented communities in the past. Gaining the trust of Canal community members will not be an easy feat, but with community-based organizations representing impacted populations, they can monitor prospective solutions to ensure they will not lead to displacement.

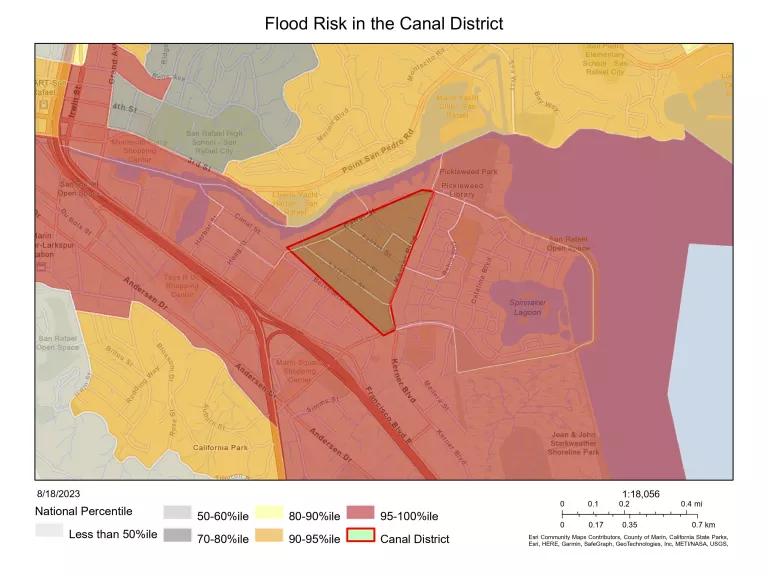

Flood risk in Canal from EJ Screen

Uplifting Community Voices Through Data

Climate change and its associated impacts disproportionately affect low-income communities and communities of color. Income, English language proficiency, and access to climate change data can affect how informed a community is about the climate-related risks in their own backyard. Socioeconomic vulnerability compounds environmental risk and can limit community involvement in mitigation efforts. Many Canal residents are aware and concerned about sea level rise, but varying levels of English proficiency and economic stressors make it difficult for my community to be as involved in important climate resilience efforts as our wealthier neighbors.

The Canal Community Resilience Planning Project recognizes the ongoing economic, social, and environmental injustices experienced by frontline Canal communities. However, they also recognize the great potential and value of robust community engagement to implement relevant climate solutions within disproportionately vulnerable communities. By elevating community roles in adaptation project planning, the most impacted communities will be able to make informed decisions about the future of their neighborhoods.

Environmental justice communities have relied on various tools and methods to address climate and social justice issues in their cities and towns. Toxic Tides, a collaborative project between non-profit community-based organizations and university partners throughout California, outlines a three-step process to identify and act upon sea level rise within communities living within and around hazardous sites.

- Identify and characterize flood risk within targeted areas.

- Create data visualizations, including mapping tools, to showcase the distribution and types of hazardous facilities in coastal communities.

- Communicate findings with advocacy groups and decision makers to implement community needs into emerging climate resilience policy and adaptation projects.

When shoreline communities have access to usable climate data, adaptation project proposals, and local and countywide support, they are better equipped to speak truth to power and protect their homes. This community-driven feasibility study may be in its early stages, but it has the potential to set the groundwork for climate resilience.

So often, low-income people are not considered environmentalists while wealthy communities get attention for their participation in sustainability. In reality, low-income neighborhoods, such as the Canal, use the most public transportation, recycle more, and engage less in consumerism. Despite this, we are forced to live in environmentally unjust areas.

The world outside of the Canal District is fearful of my community. There are even those who call for the destruction of our neighborhood. Rapid climate change threatens to do the same. This time, however, the community is building a toolkit to ensure we are on the frontlines of climate justice, not climate disaster.