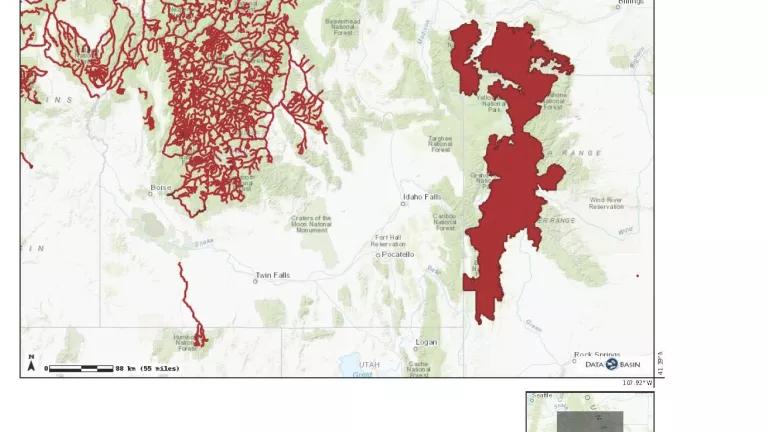

Examples of critical habitat designated by FWS for bull trout in central Idaho and Canada lynx in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (“FWS”) has made a host of changes to the rules implementing the Endangered Species Act (“ESA”). These changes will negatively impact imperiled wildlife across the country—and even across the planet—by, for example, making it more difficult to list species, removing automatic protections for threatened species, and allowing FWS to ignore detrimental “baseline” conditions that may already be putting a species at risk of extinction.

Another, particularly concerning set of revisions to the rules aims to undermine how, and how often, “critical habitat” can be used to help listed species recover.

One of the most important ways the ESA helps to protect threatened and endangered wildlife is by conserving the ecosystems that are their homes. One way it does this is by authorizing—and in many cases requiring—FWS to designate areas that are essential to species’ survival as “critical habitat.” In general, once a species’ habitat is designated as “critical,” federal agencies must “consult” and work with FWS to ensure that their actions do not degrade or destroy those areas.

This protective measure is core to the ESA’s ability to help imperiled wildlife recover. Yet, the very agency charged with implementing it—and the ESA as a whole—just weakened it in three important ways.

First, FWS created new exceptions that allow it to avoid designating critical habitat altogether. For example, it added an exception saying that, where threats to a species’ habitat (such as “melting glaciers, sea level rise, or reduced snowpack”) cannot be completely solved through the ESA’s consultation process, the agency need not bother designating that habitat as “critical” at all—even if doing so could still provide some benefits. In effect, the agency decided that when it comes to major threats to vulnerable wildlife’s habitat, rather than do all it can, it won’t do anything at all.

Second, FWS limited its own authority to designate “unoccupied” critical habitat—that is, areas where listed species do not currently live, but which are critical to the species’ future survival. Conserving unoccupied critical habitat can be crucial for a number of reasons. For example, listed species often occupy only a small percentage of their historical range—such as gray wolves (which inhabit about 15 percent of their former range in the Lower 48) and grizzly bears (which inhabit about two percent of theirs). To fully recover, these populations will need to be able to expand.

In addition, species may need to move to new, previously unoccupied areas in response to environmental changes such as a warming climate. In such cases, protecting unoccupied critical habitat may be as, or even more, important than protecting occupied critical habitat.

Wolverines - one of many species that could be negatively impacted by reduced snowpack as a result of climate change.

Third, FWS revised the ESA’s definition of “destruction or adverse modification” of critical habitat by inserting “as a whole,” so that the new definition reads:

Destruction or adverse modification means a direct or indirect alteration that appreciably diminishes the value of critical habitat as a whole for the conservation of a listed species.

While the change is subtle, the impact could be profound. It means that FWS could try to allow activities that incrementally degrade critical habitat—so long as they don’t damage the habitat “as a whole.” But taken collectively, these activities could result in the exact “death by a thousand cuts” to critical habitat that federal courts have found the ESA seeks to prevent.

These and other rule changes made to the ESA are particularly ominous—and unforgivable—in the wake of the United Nations Global Assessment Report’s predictions that human activities threaten up to a million species with extinction, many within decades. At a time when the ESA’s safeguards are more necessary than ever, the designation of critical habitat and other protective mechanisms are suddenly, somehow, themselves at risk of becoming the next endangered species.