Toledo’s Blooming Algae Crisis

A toxic algae outbreak that left Toledo without drinking water for several days in 2014 served as a wakeup call for responsible farming in the region. Efforts have been made to prevent algae blooms in Lake Erie, but a changing climate will only increase the threat.

A catfish was found on the shoreline in the algae-filled waters of North Toledo in September 2017.

Andy Morrison/The Blade via AP Photo

What happened

On a mild summer day in 2014, Capt. Paul Pacholski docked his charter boat after navigating through the lime green sludge that covered Lake Erie’s western basin. He had grown accustomed to the harmful algal blooms (HABs) that had cropped up every summer for the past decade. But the patches of blue-green algae—or cyanobacteria—were thicker than normal, clustering less than a foot below the water’s surface. They not only surrounded his dock, but the nearby intake to the city of Toledo’s water supply.

Pacholski, president of the Lake Erie Charter Boat Association, pulled out his phone and called Craig Butler, director of the Ohio Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). “We have a major problem here,” he remembers saying. When Butler arrived with a team the following Monday, tests quickly revealed that there were toxins in the water supply.

About a week after Pacholski’s discovery, in the early hours of August 2, the city of Toledo sent out a warning to local residents: Don’t drink the water. Don’t use it to brush your teeth, prepare food, or make baby formula. Don’t boil it—that will only increase the toxins in the water. Overnight, nearly half a million people no longer had safe drinking water.

As the shelves of local stores were being emptied, Ohio Gov. John Kasich called in the National Guard to help distribute bottled water. Meanwhile, researchers at the Collins Park Water Treatment Plant toiled around the clock to reduce the levels of microcystin—the powerful neurotoxin found in the blue-green algal blooms.

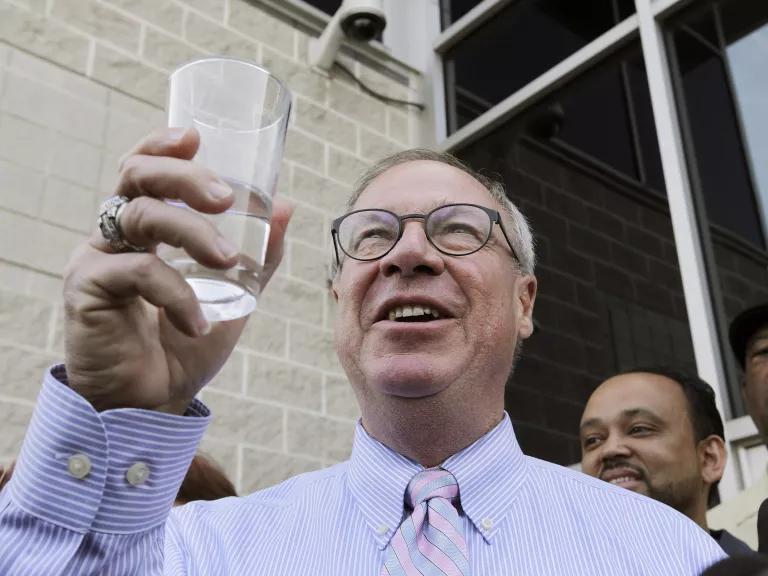

After two days, Toledo Mayor Michael Collins lifted the ban—as well as a glass of water to his mouth to show it was safe to drink again.

Even after the ban was lifted, Katie Rousseau, director of Clean Water Supply at Great Lakes for American Rivers, recalls, “my husband didn’t drink the water for a long time, and we didn’t really give it to our daughter.”

Why it's a big deal

Although HABs are called blue-green algae, they are actually a type of bacteria (known as cyanobacteria) that feeds on phosphorus and nitrogen in the water. Microcystin, a neurotoxin in the bacteria, is particularly dominant because it can control its own buoyancy to stay as close as possible to sunlight. Its ability to float near the lake’s surface allows it to outcompete other beneficial phytoplanktons. The HABs often hit their peak in August, typically the hottest month in the Midwest, because they’re exacerbated by warming air and water temperatures.

Consuming water containing cyanobacteria could cause stomach flu symptoms —such as diarrhea, vomiting, nausea—as well as liver or kidney damage. Contact with contaminated water could result in skin rashes and other allergic reactions. There is also evidence that cyanobacteria can contribute to neurodegenerative diseases like ALS, sometimes known as Lou Gehrig’s disease. But perhaps most terrifying, in 1996, a cyanobacteria contamination of water from a reservoir in Brazil was linked to the death of 50 people.

Luckily, there were no reported illnesses from Toledo’s 2014 outbreak. But the blooms, which have become near-annual occurrences over the past 10 years, are starting to take a toll on the local community. Lake Erie, known as the “Walleye Capital of the World,” boasts a nearly $13 billion tourism industry. Lucas County, home to Toledo, is expected to be among the hardest hit areas on the lake if the blooms aren’t addressed.

The local charter boat industry has already seen a decline of as much as 30 percent in recent years due to the blooms, Pacholski says, emphasizing that the overall impact is even bigger due to the trickle-down effect if tourists stay away. “When they come they eat at restaurants, spend nights in hotels for two or three days,” he says. “That’s a significant economic impact."

Why it’s happening here

The 2014 crisis wasn’t the first water shut-off in Lake Erie’s history. The summer before, more than 2,000 water users were affected in Carroll Township, Ohio, when cyanobacteria was found in their water supply. It also wasn’t the first—or the last—large-scale algal bloom in Lake Erie.

As the warmest and shallowest of the Great Lakes, Erie is the most prone to “eutrophication,” the buildup of nutrients such as phosphorus, creating prime conditions for algal blooms. For decades, Lake Erie and its tributaries have battled pollution that left the lake oxygen-starved and nearly comatose. By the 1960s, a toxic brew made up of waste from industrial belt factories along with urban sewage and fertilizer runoff from farms led some news outlets to declare that “Lake Erie is dead.”

The Cuyahoga River, a Lake Erie tributary, has caught fire many times throughout history. The pollution from industrial byproducts would create oil slicks that burned and then killed people and destroyed boats, buildings, and shipyards. In 1972, the Clean Water Act became law, imposing restrictions on industrial discharges. The same year, the United States and Canada signed the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement, with a goal of cutting Lake Erie’s phosphorus—which contributes to the growth of algal blooms—levels in half.

The Cuyahoga River, a tributary of Lake Erie that runs through Cleveland, has caught fire more than a dozen times. But it was the infamous 1969 blaze that helped inspire an emerging environmental movement. In 1972, Congress passed the Clean Water Act, which imposed restrictions on industrial discharges. The same year, the United States and Canada signed the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement, which set a goal of cutting Lake Erie phosphorus levels in half.

While the algal blooms did recede from Lake Erie over the next couple of decades, the recovery didn’t last long. By the mid-1990s new dead zones—areas where the oxygen levels are so low that the water can’t support life—began to appear, despite the fact that overall phosphorus levels hadn’t increased. There are several reasons behind the resurgence in algal blooms:

- Clean Water Act loopholes: Although it helped reduce pollutants from factories and sewage facilities, it didn’t reduce “nonpoint” sources of pollution, such as phosphorus-heavy runoff from farms. Toledo sits at the mouth of the Maumee River, and nearly 90 percent of land along this Lake Erie tributary is used for corn, soybeans, and other agricultural production.

- Phosphorus from farm runoff: While phosphorus levels have actually declined, much of it now comes in a form that is more favorable for algal blooms. Phosphorus that runs off of farm fields dissolves more easily than the phosphorus particles that have been largely banned from laundry detergents in recent decades. Soluble phosphorus can break down so quickly that within minutes of entering a lake, HABs can consume almost all of it.

- Disappearing wetlands: The Great Black Swamp, a massive wetland bordering Western Lake Erie that helped filter nutrients from runoff before they entered the lake, has been turned into farmland. Peter Bucher, water resources director at the Ohio Environmental Council, estimates that only about a tenth of the wetlands remain. “It would be ideal to get more natural filters in the form of wetlands,” he says.

Quagga mussels, an invasive species that often enter bodies of water through ship ballast water, eat healthy algae and spit out toxic algae, contributing to the growth of toxic algal blooms.

NOAA

- More invasive species: Zebra and quagga mussels, transported in via ship ballast water, filter feed on healthy algae and spit out toxic algae—helping them to thrive.

- Climate change: Warmer air and water, along with the increased risk of flooding, means the problem will likely get worse. “The Great Lakes are predicted to have strong and severe storms more frequently,” says Rousseau of American Rivers, “So the more rain, the more algal blooms we’re going to have.”

What’s being done

With the algal bloom problem only getting worse, governments at all levels are taking action. Much of the focus is on (mostly voluntary) steps that farmers can take to reduce runoff, such as adopting more sustainable practices of fertilizer use.

At the international level, the United States and Canada recently updated the Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement, committing to a 40 percent reduction of phosphorus by 2025. The cuts would largely be achieved by “best practices” in farming, such as the 4R’s (right time, right place, right rate, and right source) of fertilizer use.

To help move the binational effort forward, Ohio lawmakers approved the Clean Lake 2020 Plan in 2018, which provides funding to tackle the algal bloom problem in Lake Erie, including financial incentives for farmers to soil test, monitor water drainage, and reduce their phosphorus load.

Jerry Whipple, a farmer in Benton Township, Ohio, has received federal funding to help cover costs of best-management practices to prevent fertilizer from running off his lands into creeks that feed Lake Erie, which would then contribute to algae growth.

Paul Sancya/AP Photo

Ohio is also taking a more aggressive stance on regulating agriculture runoff, seeking to expand on a recent law that restricts the use of fertilizers on frozen, snow covered or rain soaked soil in Lake Erie’s Western Basin. Meanwhile, Ohio has joined Michigan in declaring portions of Lake Erie “impaired,” allowing state agencies to limit the amount of agricultural nutrient that can wash into the waterway.

Without regulations, it’s not clear that relying on farmers to voluntarily implement “best practices” do much to solve the problem. Bill Myers, who operates a family farm on Lake Erie, has been a believer in responsible fertilizer for almost two decades.

“One time I saw where we made an application to wheat in the normal February to March time frame,” says Myers. “We ended up with a perfect storm: The ground was still frozen, it warmed to 70 degrees, and it rained. We watched the water run off the field. I know what was in that water. It opened my eyes.”

He now tills his land in strips and applies nitrogen and phosphorus about four to six inches deep, but only where it’s needed based on soil tests. He aims for good weather—late fall or early spring—so runoff is minimal and nutrient retention is high. While it costs more and entails more work, grid sampling led to larger yields because he wasn’t leaving some parts of the field under fertilized and other parts over fertilized.

“There isn’t a farmer that doesn’t care about Lake Erie and whether it’s green or not,” says Myers, who fishes on the lake with his family. “Nobody wants to see it happen. Getting the methods in place to mitigate it as much as possible is the key.”

Meanwhile, Toledo has taken its water treatment into its own hands, launching a $500 million upgrade to the Collins Park Water Treatment Plant and posting a Water Quality Dashboard to publicize water quality. The city is also consolidating water systems with the suburbs.

“Local [water treatment] plants are doing above and beyond what the state’s asking them to do, and they have been, which is why they even had the [2014] detection,” says Rousseau, adding that the state needs to further address the source of the problem. “They’re just doing a lot on the back end in monitoring and assessing. If anything’s going to change, we’re going to have to start going field by field and doing best-management practices.”

More than five years after the crisis, Pacholski’s family members now check the water dashboard religiously, a tool on all local news and weather sites that actively monitors the water letting constituents know its toxicity level and whether it’s safe to drink.

“People are still drinking bottled water to this day rather than trusting their municipal water to be safe,” says Pacholski.

What needs to happen

One law that could go a long way to reducing the amount of nutrients that feed algal blooms is the Clean Water Rule, a law passed in 2015 that the Trump administration then repealed in September 2019. The rule would have brought the Clean Water Act into the modern era by restoring protections for wetlands and streams, which act as filters for phosphorus. First the Trump administration tried to have the Clean Water Rule suspended until 2020. After NRDC filed a lawsuit, a federal judge rejected the suspension in August 2018 and allowed the rule to take effect in 26 states. With the administration’s final repeal in September 2019, many agricultural and industrial polluters are exempt, and wetlands that aren’t connected to bodies of water, as well as streams that don’t run year round, are no longer safe. Instead of being weakened, the rule should be further strengthened to regulate agricultural fertilizers and runoff.

The Great Lakes contain about 20 percent of the surface freshwater on Earth. To protect our drinking water, the EPA must start regulating cyanobacteria, cyanotoxins, and microcystin.

The 2018 Farm Bill, created a new program to clean up lakes, rivers, and estuaries and provides funds to protect drinking water sources.

What you can do

You are a powerful player in holding the EPA and your city officials accountable. “Getting an answer out of your policy makers is my number one,” says Bucher. He wants Ohioans to ask their elected officials whether they’re supporting a clean Lake Erie and safe drinking water.

Be a watchdog on the federal budget. The Trump administration has twice attempted to cut almost all of the funding for the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative from its budget proposals. This funding program is estimated to have boosted the local economy by $3.35 for every dollar spent.

Test your water regularly. Your water supplier may do free in-home testing, or you can ask a certified lab to test your water. Call the Safe Drinking Water Hotline at 800-426-4791 to find a state-certified lab in your area. You can also order a test for lead in your water from the nonprofit Healthy Babies Bright Futures, which lets you choose how much you can pay.

Advocate for a healthier Lake Erie by supporting environmental groups like the Ohio Environmental Council, Lake Erie Foundation, Toledoans for Safe Water, Advocates for a Clean Lake Erie, or Junction Coalition.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

Millions of Americans drink tap water served by toxic lead pipes.

Tell the EPA we need safe drinking water!

Tell the EPA we need safe drinking water!

There is no safe level of lead exposure. But millions of old lead pipes contaminate drinking water in homes in every state across the country. We need the EPA to do its part to replace lead pipes equitably and quickly.

Why Are Our Waters Turning Green?

The Algae That (Almost) Ate Toledo

Flint Water Crisis: Everything You Need to Know