Wilmington’s Battle With GenX, a Dangerous Teflon Chemical

A toxic chemical discovered in the drinking water system serving communities along North Carolina’s Cape Fear River raised the alarm about contamination from the nearby Chemours chemical plant. Although levels of GenX, used to make nonstick products, have receded, the fight for safe drinking water continues.

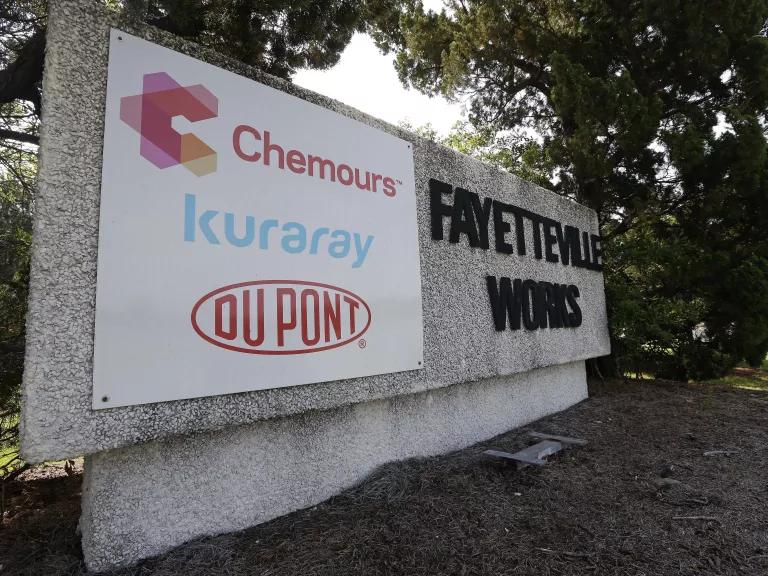

Fayetteville Works, near North Carolina’s Cape Fear River, houses a number of industrial plants, including a Chemours chemical plant that produces GenX. It turned out that the toxic chemical had been flowing for years from the plant into the Cape Fear River, the source of water for hundreds of thousands of residents in the Wilmington area.

Ken Blevins/The Star-News via AP

What happened

Patsy Sheppard knew the Chemours chemical plant in Bladen County, North Carolina, where her husband had worked for three decades, produced some dangerous substances. But she never imagined that the chemicals could end up poisoning her tap water.

In 2017, she discovered that the unimaginable had become reality, when the local newspaper reported that GenX and other toxic chemicals used to manufacture nonstick products such as Teflon had been contaminating the drinking water in the Wilmington area. The Wilmington region, which includes New Hanover, Brunswick and Pender counties, is about 100 miles down the Cape Fear River from the plant and home to nearly 400,000 people.

“We woke up one morning and found out that it had been discharged into our drinking water since the 1980s,” recalls Sheppard, whose farm and home are within miles of the Chemours facility where GenX is produced.

The discovery of GenX in the water happened by accident. In 2013, North Carolina State University scientist Detlef Knappe was collecting water samples from the Cape Fear River to study bromide—a chemical that can create risky compounds when it reacts with chemicals used to disinfect water—and found high levels of GenX and other unknown toxic chemicals.

At the time of the discovery, there was no consensus on what level of GenX in drinking water should be considered safe. However, GenX and the other chemicals discovered in Wilmington’s drinking water are part of a broad family of highly fluorinated chemicals called PFAS, which are toxic at even extremely low levels—in the low parts per trillion—in drinking water. In Knappe’s initial findings, the average concentration for GenX was 631 parts per trillion (ppt), with some samples as high as 4,500 ppt. However, in October 2019, new findings uncovered much higher PFAS levels—up to 130,000 ppt near Lock and Dam no. 1, near the drinking water intake for Wilmington.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency doesn’t regulate PFAS, though it has established health advisories suggesting that two of the most common relatives of GenX—PFOA and PFOS—are considered safe at levels below 70 ppt. However, in August 2018, an agency of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) suggested a threshold for PFOA and PFOS that was about one-tenth the EPA’s recommended level.

The North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services set a health goal of 140 ppt or less for GenX in July 2017. Meanwhile, the EPA still hasn’t established specific guidelines for GenX in drinking water—though it recently released draft toxicity assessments for GenX and PFBS, which are replacements for PFOA and PFOS. The draft toxicity assessment confirmed that GenX and PFBS are linked to harmful health effects similar to those caused by the PFAS they replaced.

When Knappe published his findings in November 2016 and forwarded copies of the paper to several state and local government officials, he initially got no response. It wasn’t until the results were reported in the Wilmington StarNews that local residents became aware of the potential dangers of their drinking water.

Chemours, which was spun off from DuPont in 2015, began producing GenX as a commercial product in 2009, touting it as a “sustainable replacement” for PFOA and PFOS, often called C8 chemicals, which have been linked to a host of health issues. However, company and state officials have suggested that the same chemical may have been flowing into the river for decades as a byproduct of production happening elsewhere in the company’s facility. (Chemours did not respond to requests for an interview.)

Traveling by water and air from the Chemours facility, GenX contamination has spread far and wide. The chemical was found in the Cape Fear River as far as 100 miles downstream from the Chemours site, in the system that provides drinking water to more than 200,000 residents in the Wilmington area. It was also found in rainwater samples taken up to seven miles from the plant.

In 2017, water testing began to determine contaminant levels in both untreated and drinking water. The Cape Fear Public Utility Authority (CFPUA) has been taking regular samples at its Sweeney Water Treatment Plant, which serves Wilmington, and results indicate that levels of GenX in the water had declined to 6.4 ppt as of December 2019. CFPUA attributes the drop—from 42 ppt in January 2018—to state enforcement actions taken in September 2017 to force Chemours to stop releasing GenX and other PFAS into the river.

Samples were also taken from more than 400 local wells between September and November 2017; about 70 percent tested positive for GenX, including nearly a third with levels exceeding the state’s 140 ppt health goal. In one well, the levels of GenX topped 4,000 ppt. Then in November 2019, it was reported that as many as 1,000 more wells were found to be contaminated.

Why it's a big deal

GenX was developed to replace C8 (PFOA and PFOS), man-made chemicals used in nonstick cookware and fabric protection that have been linked to cancer, thyroid disorders, developmental and immune issues, adverse effects on women’s fertility and pregnancies, and other health problems.

NRDC staff scientist Anna Reade notes that GenX was reputed to be safer than C8 because it has a shorter carbon chain. Since it is thought that our bodies can eliminate shorter-chain chemicals faster, chemical companies argue that makes them less toxic. But studies have linked GenX to several of the same diseases linked to C8 exposure, including effects on the kidneys, liver, immune system, and thyroid. Furthermore, because GenX does not break down, it will build up in our environment, resulting in continued exposure; this suggests that the speed at which GenX is eliminated from our bodies is an inadequate measure of its threat to human health.

Unfortunately, as Reade notes, the EPA does not require a full array of safety testing before chemicals like GenX are widely used, so she believes it’ll take time to understand the whole range of health risks that GenX poses to us. “Every time new chemicals are released into the market, the independent science community has to play catch-up,” Reade says. “It takes a long time for scientists to run all the different types of studies that are needed to fully understand what all the possible health effects associated with these chemicals will be. This is followed by the additional time it takes to regulate and clean up these toxic chemicals. All the while, we and our families are being exposed and our health put at unnecessary risk.”

Wilmington resident Ocean Priselac is so concerned about the potential health effects of GenX that she stopped drinking tap water and eating local food, including fresh produce and seafood, as soon as she heard about the contamination. She believes the ill effects of GenX contamination are already popping up among people and animals in the community. So far there’s no evidence that cancer rates in nearby counties are higher than those elsewhere in the state; however, the EPA determined that there is evidence to suggest that GenX can cause cancer in humans, based on the occurrence of pancreatic and liver tumors in rodents exposed to GenX.

Priselac was one of 345 residents of New Hanover County, a community that gets its water from CFPUA, to have their blood and urine tested for exposure to GenX by researchers from North Carolina State University in November and December 2017. The results of the GenX Exposure Study showed that four PFAS compounds were present in the study participants’ blood, though GenX was not detected. The results of the urine samples were pending at the time of publication.

Priselac’s blood tests did show levels of several PFAS chemicals, including NAFION byproduct 2, which is also produced at Chemours’s plant in Bladen County. Little is known about this chemical, which principal investigator Jane Hoppin, deputy director of the Center for Human Health and the Environment at North Carolina State University, refers to as a “newly identified” compound that was also found in the Cape Fear River. “I have all of these cancer contaminants in my body and I’m angry,” Priselac says. “I want to know what it’s going to take to shut [Chemours] down.”

One finding stood out to Hoppin: Among the residents who were tested, the median level of PFOA was four times higher than the median level of PFOA nationwide; she says levels of PFOS were twice as high as the national level. “There was an audible gasp in the room when we shared the fact that PFOA levels were so much higher than the general population,” Hoppin recalls, describing the meeting where researchers unveiled the results of the blood tests. “It would be hard to argue that the people in Wilmington have a much different use of consumer products than everyone else in the United States, which tells us that there’s probably some environmental source contributing to that.”

Getting access to safe drinking water is an issue for millions of Americans, but contamination often disproportionately affects low-income communities of color. This is certainly true for Wilmington.

The Chemours plant is located in Bladen County, where about 42 percent of the 33,000 residents are African American or Latino and more than a quarter of residents live below the poverty line. The demographics are similar in neighboring Cumberland County: More than half of the 332,000 residents are people of color, and almost 19 percent of them live below the poverty line.

“It’s not like people here can afford to sell their homes or just walk away. Who wants to buy a home where the water is contaminated by GenX, C8, and numerous other chemicals?” asks Sheppard, adding that she believes polluters choose to operate in lower-income communities because of their lack of economic or political power.

Community response

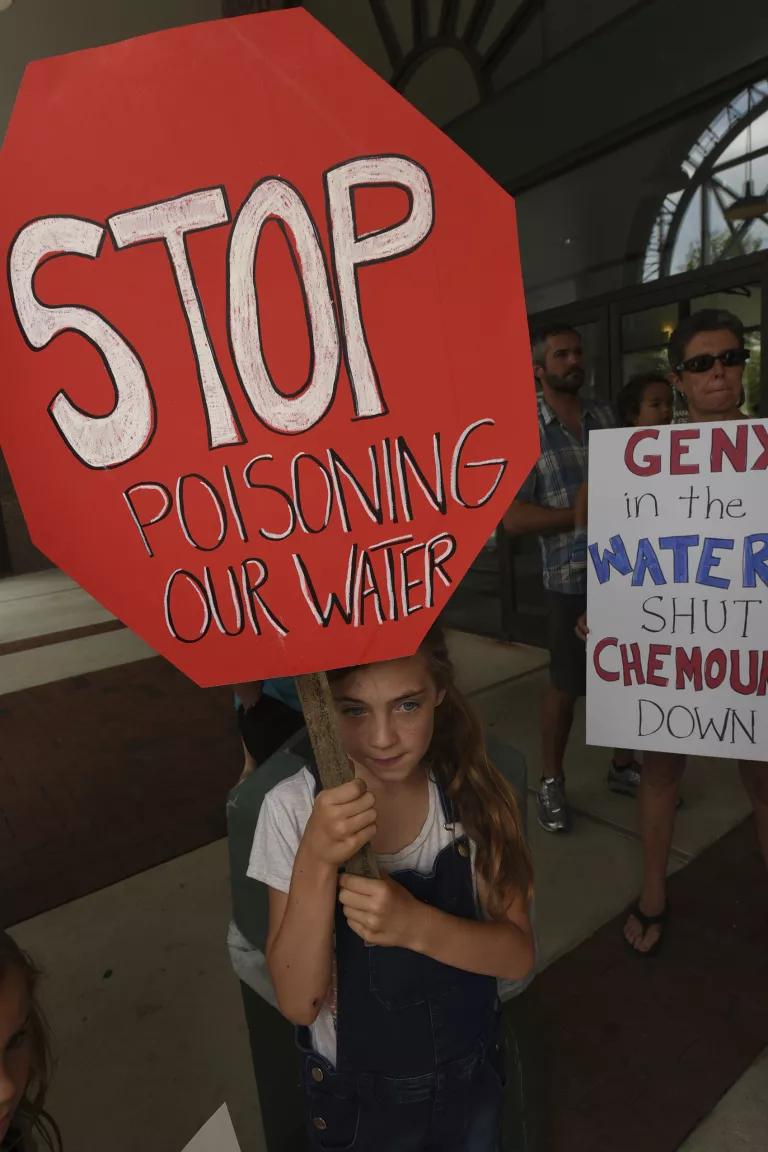

When word of the contamination hit the news, outraged local communities took action—staging protests, contacting county officials, attending local government meetings, and demanding information and action. Residents formed anti-GenX Facebook groups to share information and ideas for addressing the contamination.

Sheppard compares the situation in North Carolina to a similar crisis that occurred in Parkersburg, West Virginia. Residents brought a class action lawsuit against DuPont in 2001 after an alleged C8 leak that contaminated local water supplies. Lawsuits were settled in 2017, and DuPont and Chemours agreed to pay plaintiffs $671 million, though both companies denied wrongdoing. “DuPont stalled the residents of West Virginia for 20 years, and we don’t expect it to be any different here,” Sheppard says.

Though Sheppard and other frustrated residents are no longer taking to the streets as much, they are taking the issue to the courts. Several class action lawsuits against Chemours and DuPont have been merged into one that represents thousands of residents who live along the Cape Fear River, seeking damages as well as funding to study the health impacts of GenX and other chemicals that have been discharged by DuPont and then Chemours. Sheppard says she plans to file her own lawsuit against Chemours.

The CFPUA, the North Carolina Department of Environmental Quality (NCDEQ), and Cape Fear River Watch also sued Chemours. The Southern Environmental Law Center (SELC) filed two suits against the chemical company, on behalf of Cape Fear River Watch, but they agreed to drop the suits in November 2018 as part of a consent order requiring Chemours to clean up the pollution and provide treated drinking water to residents with contaminated wells. The company must also pay a $12 million civil penalty to the NCDEQ, the highest ever for the agency, plus additional fees if it fails to reduce its annual emissions.

Following a public comment period, the proposed consent order was modified to include a provision that gives downstream public water utilities a say in how Chemours can reduce its pollution in the Cape Fear River and a second provision requiring the company to study the sediment pollution in the river. SELC senior attorney Geoff Gisler called the consent order a path to a “cleaner Cape Fear,” noting that the goal was to get Chemours to take responsibility for the contamination, start cleaning up the groundwater, and control the discharge of GenX and other chemicals.

However, the CFPUA argues that the consent order favors people who get their water from wells over the utilities’ customers. The utility also wants Chemours to be responsible for cleaning up contaminated sediment at the bottom of the river.

What has been done so far

Multiple agencies at the federal, state, and local levels have been tasked with addressing the issue of water contamination from GenX. Their progress—and response times—have been mixed.

The state’s response to the crisis has been caught up in local politics. Legislators have funded NCDEQ at a level well below what the agency has said it needs to address the situation while giving money and authority to test water quality to a university-led consortium. A StarNews editorial blasted legislators for passing a budget—including a vote to override the governor’s veto—“that puts the interests of industry ahead of the very legitimate safety and quality-of-life concerns of the people they are supposed to be representing.”

State legislators also provided funding to CFPUA in 2017 and 2018 for water sampling and testing alternative technologies for treating local drinking water. CFPUA ran a pilot test to determine whether various technologies—granular activated carbon (GAC), ion exchange, or reverse osmosis (RO)—could remove PFAS from water supplies.

Crews work outside at the Cape Fear Public Utility Authority (CFPUA) Sweeney water treatment plant, which is supposed to go through upgrades starting November 2019 to try to remove GenX.

Ken Blevins/The Star-News via AP

CFPUA began construction in the fall of 2019 to upgrade its Sweeney plant with new GAC filters that it hopes can remove GenX. Part of the estimated $43 million cost will be passed on to customers, whose monthly water bills are expected to increase by about $5 starting in July 2020. However, more recent studies have found that replacement chemicals such as GenX are more difficult to capture through GAC filters. Reade believes that, with proper design and maintenance, GAC filters can be effective for filtering the original PFOA chemical from water supplies, but their effectiveness on GenX is questionable. A report provided to Brunswick County noted that a supplemental ultraviolet or ozone advanced oxidation process would need to be used in conjunction with GAC to achieve stated targets for the removal of contaminants.

About $2 million in state budget money will also go toward helping residents whose private wells are contaminated with GenX get connected to local municipal water systems, with Chemours reimbursing the money. The company has studied the feasibility of either connecting nearby homes in Bladen and Cumberland counties to municipal water or installing GAC filters.

In May 2018, the Board of Commissioners in Brunswick County voted to implement RO at its Northwest Water Treatment Plant at an estimated cost of $99 million for implementation and an annual cost of $2.9 million for operations and maintenance. In one report, RO proved to be the most effective treatment for removing a broad range of PFAS chemicals and protecting against future unidentified PFAS compounds. According to reports, however, the plant is planning to discharge the RO reject water, which will contain concentrated contaminants including PFAS, directly back into the river. While the drinking water will be safer, says Tracy Quinn, a water conservation and efficiency expert at NRDC, there are concerns about the impact of the discharge. Bidding has been delayed, but a contract is expected to be awarded in May 2020.

Chemours has also pledged to invest $100 million at its Bladen County plant to control air and wastewater emissions, with plans to install a thermal oxidizer and carbon absorption beds, upgrade a waste gas scrubber, and use enhanced leak detection equipment.

What needs to happen now

The consent order with Chemours, which was approved by the Bladen County Superior Court in February 2019, is a starting point, forcing the company to clean up the contamination and protect against further discharges in the air and water. The NCDEQ, along with Cape Fear River Watch and other activists, must stay vigilant to ensure the company lives up to the agreement.

Meanwhile, Chemours should be forced to compensate residents for any health impacts related to the contamination and to help affected public water systems like Wilmington/CFPUA recoup the cost of PFAS testing and upgrades to its treatment facilities.

North Carolina legislators, who have long starved the NCDEQ’s budget, need to provide the agency with the funding and authority to take the necessary action to ensure safe drinking water in the state. They should also set “strong limits” on dumping contaminants, as the local Fayetteville Observer urged in a recent editorial.

In the absence of federal leadership on safe drinking water under the Trump administration, “states must immediately step into the breach and issue strong, health-protective drinking water standards and cleanup requirements,” says Erik D. Olson, senior director of health and food at NRDC.

Finally, the EPA needs to step up and remedy its failure to address the threat of GenX and other PFAS to public health and the environment, say Olson and Reade, including by:

- meaningfully regulating the manufacture and use of PFAS;

- issuing standards to protect our drinking water;

- preventing the spread of PFAS contamination; and

- ensuring contaminated sites are cleaned up.

What you can do

First, get informed. The PFAS threat isn’t limited to North Carolina. A study by Harvard University researchers found that drinking water supplies in 33 states are contaminated with PFAS, with the tap water of more than six million U.S. residents exceeding the EPA’s health advisories. The Environmental Working Group has a map showing where PFAS have been detected.

As residents such as Sheppard and Priselac illustrate, you can be a powerful force for change and ensuring your right to safe water. Hold polluters accountable, demand action to stop new PFAS contamination, and help push to fund drinking water testing and cleanup by calling your member of Congress, state legislator, or town councilmember. At the federal level, demand that Congress and the EPA start regulating GenX and other PFAS.

This NRDC.org story is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the story was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the story cannot be edited (beyond simple things such as grammar); you can’t resell the story in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select stories individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our stories.

Millions of Americans drink tap water served by toxic lead pipes.

Tell the EPA we need safe drinking water!

Tell the EPA we need safe drinking water!

There is no safe level of lead exposure. But millions of old lead pipes contaminate drinking water in homes in every state across the country. We need the EPA to do its part to replace lead pipes equitably and quickly.

The Drinking Water Crisis That North Carolina Ignored

“Forever Chemicals” Called PFAS Show Up in Your Food, Clothes, and Home

The Fight for Safe Drinking Water Doesn’t Start at the Top