As the Amazon Burns, Jaguars Burn With It

How Brazil’s blazes are devastating for these big cats—and for so, so, so much more.

A jaguar in the Brazilian Amazon

Claus Meyer/Minden Pictures

A jaguar’s fangs can pierce the armored skin of a crocodile, and its jaws can crush a croc’s skull. The cats are strong, quick, and cunning—but they’re no match for a wall of fire.

Over the past two months, farmers in Brazil have turned more than seven million acres of the world’s largest rainforest to ash through tens of thousands of fires, lit with the tacit approval of President Jair Bolsonaro. All cross the Amazon, the total 7,000 square miles of scorched earth is just smaller than the state of New Jersey. Burning “the lungs of the world” is an obvious nightmare for climate and air quality concerns, but scientists are also fearful of what it might mean for Amazonian wildlife.

The Amazon is home to an estimated one in ten species on earth, so the fires’ potential impact on biodiversity is enormous. Many of those plants and animals are also small, poorly known, or rarely seen, making it difficult to measure the true consequences of this ongoing disaster.

“While the fires burn, there exists the possibility that we are losing species that are still unknown to science,” says Nigel Sizer, chief of programs at the Rainforest Alliance, a nonprofit that specializes in protecting tropical forests.

South America’s largest predator, the jaguar, has more eyes on it than most. According to Panthera, the global wild cat conservation organization, the blazes in Brazil and Bolivia alone may have displaced or straight-up killed around 500 jaguars so far. (There are also fires burning in Peru and Paraguay, so that number could be even greater.)

You might assume that many species—especially the larger ones—could flee to safety as soon as they smelled smoke. But the evidence says otherwise. “We’ve got these pictures of marsh deer being burned down,” says Esteban Payán, a South America regional director for Panthera. “And these are big, 60-kilogram [132-pound] deer that can outrun a jaguar.”

Forest fires don’t always burn in straight lines, and animals can get trapped in rings of flame from which there is no escape. Coming into direct contact with a blaze also isn’t necessary; an animal can die just as readily from smoke inhalation or radiant heat. Payán says the fires are also capable of moving so quickly and becoming so hot that they can actually leap across rivers.

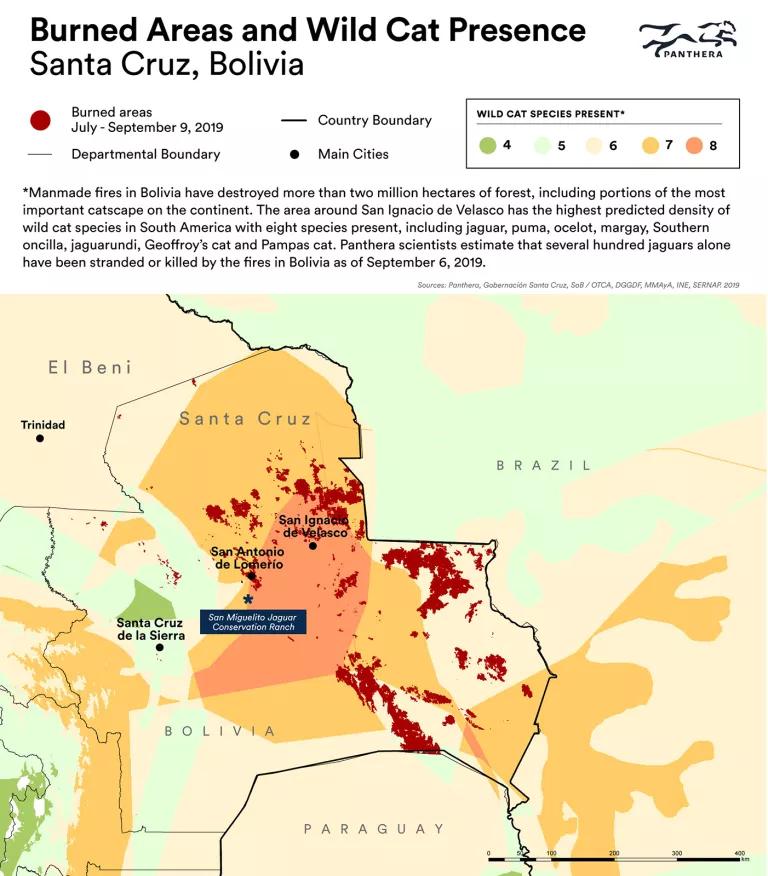

This summer's fires (shown in dark red) burned through much of Bolivia's most diverse big cat habitat (in orange and peach).

Source: Panthera, Gobernacion Santa Cruz, SoB/OTCA, DGGDF, MMAyA, INE, SERNAP, 2019

Jaguar mothers and their young cubs will likely be the hardest hit. The cats commonly give birth to litters of two or three (or more) cubs, but the females can move only one cub at a time to safety by grasping them with their mouths. Smaller animals also become dehydrated faster in the face of extreme heat, notes Payán. At best, he says, maybe a single cub in a litter will survive.

The same goes for other big cats. Many of the fires in Bolivia are occurring in a particularly biodiverse region Payán calls “the catscape,” an area that includes dry forests like the Cerrado and Chiquitano, and the wetlands of the Pantanal.

“This is the only place on the entire American continent that holds eight species of wild cats,” he says. In addition to the jaguar, there are pumas, ocelots, Geoffroy’s cats, pampas cats, margays, oncillas, and jaguarundis roaming the catscape. The area is also home to tapirs, black caimans, anacondas, turtles, tortoises, sloths, anteaters, and armadillos, as well as innumerable species of birds, insects, arachnids, plants, and fungi. Again, those are just the species we know about.

Fires scorch ridgelines near Cali, Colombia (top) and burn through Brazil's Pantanal (bottom).

Top: Esteban Payan/Panthera. Bottom: Mario Haberfeld/Pantanal/Onçafari Jaguar Project

Fanning the Flames

Fire is nothing new to the Amazon. Agricultural interests and other developers have been clearing the rainforest with fire for decades, but the rate and scale of the burning is growing at a breakneck pace. Since January, satellite imagery has detected more than 80,000 fires, a crisis level not seen since 2013. Sadly, this uptick comes after around a decade of decreasing deforestation, following a particularly destructive period in the mid-2000s. In August the fires were so intense that the smoke drew a Mordor-like curtain of darkness over São Paolo, the largest city in the Western Hemisphere.

President Bolsonaro is a notorious climate denier and has said that the Amazon is Brazil’s to do with as it pleases. He even called the satellite imagery—produced by his own government’s National Institute for Space Research—nothing more than lies. For this guy, deforestation is a feature, not a bug. In 2018 he even campaigned on a pledge to develop the rainforest.

There is plenty of blame to go around, though. Earlier this year, Brazil announced a new international agreement that would open up the Amazon even further to private-sector development. And who would be the country’s biggest partner? “The Brazilians and the American teams will follow through on our commitment that our presidents made in March,” U.S. Secretary of State Mike Pompeo recently told reporters.

Top: The burned remains of a Paraguayan caiman and a snake in the Brazilian Pantanal. Bottom: What's left of a giant anteater in Bolivia.

Top: Mario Haberfeld/ Pantanal/Onçafari Jaguar Project. Bottom: Juan Carlos Urgel.

Incredibly, the two governments suggest that developing the Amazon is the only way to save it, pointing to an 11-year, $100 million commitment to something called the Impact Investment Fund for Amazon Biodiversity Conservation. The proposal “is utterly preposterous,” says Sizer, especially when you consider that the type of development we’ve seen so far in the Amazon is destructive by definition. Oil and gas drilling, logging, intensive agriculture—all require clearing forest.

It’s also worth noting that Brazil isn’t clearing the Amazon to feed its own people. It is the largest exporter of beef in the world, and the United States imported $263 million worth of that meat last year. U.S. consumers may also be unwittingly supporting Amazon deforestation through the supply chain for leather (used in everything from handbags to luxury vehicles) and, according to Stephanie K. Baer at BuzzFeed News, by banking with financial institutions, such as JPMorgan, Chase, and BlackRock, that underwrite the beef industry.

The Backfire

The response to this summer’s fires has been swift and fierce. In August, protesters took to the streets across Brazil, as well as outside Brazilian embassies in Switzerland, France, Cyprus, and the United Kingdom. Global leaders, including Pope Francis and the G7, commented on the fires publicly and pressured Bolsonaro to act (so far, to no avail).

Outrage has inspired action, too. At a recent U.N. summit, world leaders offered to donate $500 million to support the effort to save tropical forests, including the Amazon. And in the month of August alone, the Rainforest Alliance received around $500,000 in donations from concerned citizens all around the world. Sizer says the organization has already sent all of the new funds to conservation organizations on the front lines, including the indigenous organization COICA, an agriculture NGO called IMAFLORA, and others such as the Instituto Socioambiental and Imazon.

This puma in Bolivia escaped the flames and now awaits its release.

DIRCOM-GOB DPTAL DE SANTA CRUZ

In addition to improving the monitoring of fires and identifying future high-risk areas, Sizer says that “with the money, these groups plan to train community fire brigades in the critical crisis regions to fight small fires before they burn out of control.” Also on the priority list is supporting media reporting on the issue so the devastation doesn’t disappear from the public eye.

Right now the forest is smoldering, and the fates of the 500 jaguars are not yet known. Regardless of whether they outran the flames, their previous habitat is gone. Other Amazonian inhabitants, however, weigh even heavier on Payán’s heart.

“The indigenous peoples are the great losers here,” he says. “They’re homeless now, and these lands are probably lost forever.” Payán says that unscrupulous or simply irresponsible farmers and ranchers will soon come to colonize these lands and take them for their own. “They won’t go back to contributing to nature,” he says of the forestlands.

Donations help, of course, but over the long term, it might be a good idea for us to examine why these fires were started in the first place and how the choices we make as consumers might be acting as lighter fluid. Because next year, unless something changes, the Amazon rainforest will burn again, further jeopardizing the people, the species, and the planet it supports.

This article was originally published on onEarth, which is no longer in publication. onEarth was founded in 1979 as the Amicus Journal, an independent magazine of thought and opinion on the environment. All opinions expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the policies or positions of NRDC. This article is available for online republication by news media outlets or nonprofits under these conditions: The writer(s) must be credited with a byline; you must note prominently that the article was originally published by NRDC.org and link to the original; the article cannot be edited (beyond simple things such grammar); you can’t resell the article in any form or grant republishing rights to other outlets; you can’t republish our material wholesale or automatically—you need to select articles individually; you can’t republish the photos or graphics on our site without specific permission; you should drop us a note to let us know when you’ve used one of our articles.

The Long, Long Battle for the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge

In Planning for Climate Change, Native Americans Draw on the Past

Alaska’s Tongass National Forest Gets the Protections It Deserves