Delivering Ambition, Action, and Equity at COP28

Countries, companies, investors, and all decision-makers need to deliver several key actions at COP28 to set the world on track this decade.

Mohamed bin Rashid Solar Park, UAE

IRENA

We left the last climate summit in Egypt – COP27 – with countries showing a path forward to deliver more equity, implementation, and ambition in the global response to climate change. But we need them to act with much greater urgency.

We are off-track: The Global Stocktake

Here’s where things stand right now: implementation of countries' current nationally determined contributions (NDCs) to the Paris Agreement could result in global temperatures reaching around 2.5°C by the end of this century. However, if the world fully delivered all the commitments for net zero from countries, companies, investors, and key sectors, we could be on a trajectory to hold temperatures to 2°C—short of the 1.5°C goal, and that's only if every pledge is delivered.

As a result of this emissions gap, communities are already facing mounting impacts of climate change. That damage will only get worse if we don’t act swiftly to reduce emissions this decade. Moreover, the cost of adaptation has gone up by 50 percent from previous estimates.

In developing the Paris Agreement, the world recognized that we would need to continually strengthen action to reduce emissions, support the most vulnerable in addressing the impacts of climate change, and mobilize finance to deliver the necessary actions at scale. The agreement included a key mechanism—the Global Stocktake. This mechanism is to both look backward—to recognize that we aren’t yet on track to meeting the Paris Agreement's goals—and, most importantly, to chart a path forward to close the gaps in this decisive decade for the climate. At COP28, countries need to agree to a negotiated outcome that respond to these gaps through a set of global, national, and sectoral actions to mobilize more emissions reductions, greater support for adaptation, and scaled-up resources to meet the scope of the challenge.

Agreeing to phaseout fossil fuels and ramp-up clean energy

In responding to the Global Stocktake, countries need to commit to phase-out fossils and increase renewable energy, energy efficiency, smart transportation, and clean industry. This must materialize in a series of important commitments and actions at COP28.

Committing to a just and equitable fossil fuel phase-out. All major economies need to demonstrate their ambition to break free from fossil fuels. This is not hypothetical or some abstract goal for a far-off date. It is urgent. The dramatic ramp-up in access to renewable energy, efficiency, and storage this decade enables all countries to commit to a rapid and equitable phase-out of fossil fuels in the negotiated COP outcome. This is a matter of survival and global justice for vulnerable countries on the frontlines of the climate crisis.

The world’s wealthiest and most polluting countries need to lead in phasing out of fossil fuels first and fastest, and must pair it with immediate support for poorer countries to affordably access renewable energy, energy storage, and grid solutions to power their development. That means boosting efforts to mobilize the $1.5-2 trillion in annual energy transition investments needed for lower-income countries by the 2030s. It also means demonstrating concrete steps at COP28 to deliver that support, through, for example, stepped-up finance for the renewable energy aspirations of Africa and other regions.

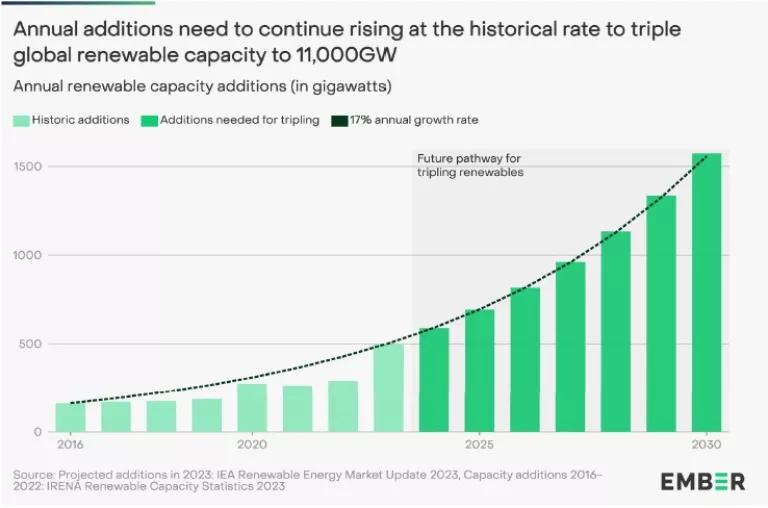

Tripling renewable energy and doubling energy efficiency. World leaders must set a global goal of at least tripling global renewable energy capacity to reach 11,000 gigawatts by 2030. According to analysis from leading experts, including IEA’s Net Zero update, IRENA’s Energy Transition Outlook and Bloomberg New Energy Finance, this renewable energy goal is achievable and necessary, although it will be a challenge (see figure). It will require “mobilizing approximately 1.5 gigawatts of new wind and solar capacity additions per year through 2030.”

Ember, https://ember-climate.org/insights/research/tracking-national-ambition-towards-a-global-tripling-of-renewables/

This expansion of renewable energy must be coupled with at least “doubling of the rate of energy efficiency improvements” by 2030 to enable a greater buildout of renewable energy and ultimately reduce the overall need for fossil fuel power plants to run. The IEA Net Zero report shows that tripling renewables and doubling energy efficiency, including a large step-up in electrification, will deliver two-thirds of the total emissions reductions needed by 2030 to put emissions on track. Rich countries must lead in demonstrating a concrete roadmap to meet these goals while supporting developing countries by mobilizing the essential financial and technical, and support building in-country renewable energy supply chains.

Addressing coal-fired power plants. The goals to triple renewable energy and double energy efficiency must be achieved in conjunction with a commitment to stop the construction of new coal-fired power plants without significant emissions controls and rapidly reducing emissions from existing coal power generation if the world is to keep the 1.5°C target alive. More specifically, coal emissions need to be phased-out in OECD countries by 2030 and non-OECD countries by 2040. At COP28, countries need to commit to ending the expansion of coal and beginning the rapid decline of coal power plant emissions this decade.

China is leading the world in the construction and utilization of renewable energy with 300 GW of new wind and solar capacity additions in 2023 alone, with its future planned investments in solar and wind setting it up for achieving the 2030 goal of tripling renewables capacity. While China leads the world in clean energy investment and utilization, it will need to combine these efforts with an accelerated shift away from coal power as the core of its power system to build a new energy system centered on renewables, and implement the goals it set in 2021 to “strictly control coal-fired power generation projects” and phase down coal consumption starting in the 15th Five Year Plan (2026-30).

In the Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) countries—South Africa, Indonesia, and Viet Nam—developed countries must help mobilize the resources necessary to unleash the early retirement of their coal fleet and the JETP countries need to stick with their commitments. At COP28, the final investment plans for Indonesia and Viet Nam will be released. These should detail the challenging but necessary path ahead to implement their coal transition commitments.

Aligning oil and gas with 1.5°C. According to the IEA’s latest update, for the oil and gas sector to align with 2050 net zero goals, the world needs to implement stringent, and efficient policies to spur clean energy deployment and cut fossil fuel demand more than 25 percent by 2030 and almost 80 percent in 2050. Under its Net Zero Scenario, the IEA expects oil demand to decline from around 100 million barrels per day (mb/d) to 77 mb/d by 2030 (a 23 percent decline). It sees fossil gas demand declining from 4,150 billion cubic metres (bcm) in 2022 to 3,400 bcm (an 18 percent decline) in 2030—and rapidly head to a 75 percent cut in emissions by 2040—under this scenario. The IEA suggests that “no new long-lead time upstream oil and gas projects” are required under this 1.5°C aligned scenario.

Developed countries must urgently stop fossil gas related infrastructure growth, reduce supply, and eliminate dependency on imports. They need to reassess their net-zero aligned energy transition plans without relying on new fossil gas power plants as a “bridge-fuel”. The U.S. as the world’s largest producer of fossil gas and exporter of liquefied natural gas (LNG), must dramatically change course. The steep emissions reductions inside the U.S.’s borders this decade could be entirely offset by increases in U.S. fossil fuel exports. It's high time for the U.S. to bring its fossil fuel policies into the 21st century. That means the Department of Energy (DOE) and Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC) overhauling their outdated guidelines for reviewing fossil gas projects, finally ending public support for all fossil fuels from U.S. Export-Import Bank and Development Finance Corporation (DFC), and supporting an OECD-wide fossil fuel finance exclusion policy during OECD Export Credit Agency negotiations.

Mobilizing for better cooling. In a warming world, one of the largest drivers of electricity demand will be cooling equipment. Accounting for about 7 percent of global greenhouse gas emissions currently, emissions from both refrigerant and energy use in cooling is expected to triple by 2050. An estimated 3 billion additional new air-conditioners will be installed globally by 2050. The air conditioners we use, the refrigerators that keep our food cold, and the way we construct our buildings is in desperate need of a revamp. In an increasingly warming world, cooling is no longer a luxury, but a tool for survival. How the world “cools” itself is a critical new challenge that is poised to receive major attention at COP28. The UAE COP Presidency has prioritized sustainable cooling as an action agenda for this COP and will be releasing a Global Cooling Pledge put together with the UNEP led Cool Coalition. The Pledge calls on governments and other stakeholders to commit to action on cooling by abiding with time bound targets. We expect that more countries and companies will commit at COP28 to mobilize stronger air conditioner appliance efficiency standards, faster adoption of climate friendly refrigerants, stronger building codes that include passive cooling strategies, and resources to help developing countries avoid a massive increase in the emissions associated with cooling and build right from the start. This COP provides the opportunity for the world to come out stronger on cooling and deliver innovative solutions on technology, finance, policies and partnerships especially for the global south.

Implementing the loss and damage fund

At last year’s COP, governments agreed to establish funding arrangements to assist vulnerable developing countries to respond to loss and damage, including creating a dedicated fund. This year, implementation will be a focus.

Approving the loss and damage fund’s governing instrument. All year, a Transitional Committee of governments representing all regions of the world have been developing recommendations on how to stand up the fund. In early November, the Committee reached consensus on a proposal for the governing instrument that would formally establish the fund. The fund would support particularly vulnerable developing countries; have a streamlined and rapid approval process; disburse funding through a variety of channels, including direct budget support to national governments; use a variety of financial instruments, including grants and highly concessional finance; and initially be hosted by the World Bank with an option to move it elsewhere at a later date.

These recommendations will be put to COP28 for consideration and adoption. The consensus text represents a delicately negotiated balance, and should be adopted in full at COP28 so the Fund can get to work supporting vulnerable countries as soon as possible.

Contributions to the loss and damage fund. Following the Transitional Committee’s consensus proposal, several rich countries have indicated that they are preparing to announce initial contributions to the Loss and Damage Fund at COP28. The EU Climate Commissioner Wopke Hoekstra announced the EU and its member states were preparing to “make a substantial financial contribution” to the fund at COP28, while U.S. Special Presidential Envoy for Climate John Kerry has said the U.S. “will put several millions of dollars into the Fund at the COP.”

These early indications of pledges are very welcome. Previous UN climate funds have taken years to begin operating, between their creation and government pledges. Such early pledges are unprecedented and indicate a desire to get the fund operating as soon as possible. A key thing to watch will be whether other rich and high-emitting countries that are significant contributors to the climate crisis and have significant capacity to provide support, such as the United Arab Emirates and Saudi Arabia, will step up and contribute.

Keep track of pledges to the loss and damage fund at NRDC’s COP28 Climate Fund Pledge Tracker.

Mobilizing the full suite of sources of loss and damage finance. Countries need to mobilize funding through a variety of mechanisms.[JS1] For example, developing countries have significant debt challenges tied to climate impacts that can be addressed through debt relief measures. The multilateral development banks (MDBs)—such as the World Bank and multilateral climate funds—must accelerate the speed of resource disbursement following a disaster. The nature of recovering from disaster is that the need for resources is immediate, not gradual. And other existing funding mechanisms must be better equipped and, if necessary, adapted to effectively address loss and damage.

Mobilizing more climate finance

To meet the Paris goals there is a need for significantly scaled up climate finance. In 2022, total global climate finance reached a record $1.4 trillion, but it needs to reach over $5 trillion per year by 2030, more than a three-fold increase. But most climate investments are taking place in major economies: China, the U.S., Europe, Brazil, Japan, and India. Developing countries are getting left behind. There are several fronts on which COP28 can advance progress for these nations.

Delivering on the $100 billion per year target. Developed countries must provide more assurances that they have finally delivered on their commitment to mobilize $100 billion a year in climate finance for developing countries. The goal was first set in 2009 and was due in 2020, but developed countries missed the deadline. The latest published data is for 2021 and shows developed countries still fell $10.4 billion short that year (see figure).

Source: Joe Thwaites/NRDC

The OECD has said that, based on preliminary but unverified data, it expects the goal will be met in 2022. Recent reporting by MDBs and the European Union show significant increases in their 2022 climate finance, which adds confidence to this projection. But given past failures, the onus remains on all developed countries to report their climate finance data transparently. This applies particularly for the United States, which is behind other developed countries in meeting its climate finance commitments. A State Department official recently indicated that in 2022 its climate finance “was nearly $6 billion, of which $2.25 billion was grant-based.” But until the U.S. and other developed countries release proper reporting, questions about the $100 billion will linger.

Developed countries committed to mobilize $100 billion a year between 2020 and 2025, so even once they meet the $100 billion, they should aim to exceed this in 2023, 2024 and 2025, to make up for the $27 billion shortfall in 2020 and 2021, and ensure their contributions across the period 2020 to 2025 average at least $100 billion a year.

Despite the emphasis developed countries have placed on the private sector to help meet climate investment needs, mobilized private climate finance has remained stagnant for the last five years, even as the amount of public finance has grown. The majority of the mobilized private finance has been going to middle income countries; the private sector is not delivering for the poorest and most vulnerable countries.

One nascent and potentially positive trend is that in 2021, the share of grant finance provided by developed countries increased, while the share of loans decreased. This may be a sign that developed countries are responding to concerns that providing climate finance as loans may exacerbate the sovereign debt crises many developing countries are struggling with.

Doubling adaptation finance. At COP26, developed countries committed to at least double their adaptation finance from 2019 levels by 2025. This would be an increase from $20 billion to $40 billion, based on OECD data. This commitment recognized that adaptation has comprised only around a quarter of developed countries’ climate finance. In 2020, developed countries’ adaptation finance jumped by $8.3 billion to $28.6 billion, 34% of all climate finance that year, raising hopes that the doubling goal might even be met ahead of time. However, two recent reports have tempered this optimism. Adaptation finance fell by $4 billion in 2021 to $24.6 billion, according to the OECD, with 27% of total climate finance from developed countries. Meanwhile, the UN Environment Program updated its estimates of adaptation finance needs to $215-387 billion per year this decade, more than 50% higher than previous estimates.

One way developed countries can help get adaptation funding back on track is to make new pledges to multilateral adaptation-focused funds such as the Adaptation Fund and Least Developed Countries Fund, as well as the Green Climate Fund, which directs half of its funding to adaptation projects. They have proven track records in rapidly delivering grant-based funding to vulnerable countries. Indeed, multilateral climate funds were the only category of institutions to see growth in their adaptation finance.

Keep track of pledges to these funds at NRDC’s COP28 Climate Fund Pledge Tracker.

Replenishing the Green Climate Fund. The Green Climate Fund (GCF) is the world’s largest multilateral fund dedicated to helping developing countries address the climate crisis. The Fund is undergoing its second replenishment this year. So far, 25 countries have pledged a total of $9.3 billion to it, short of the $10 billion committed to prior fundraising rounds in 2014 and 2019. Previous major contributors, including the United States, Sweden, Italy, Switzerland, and Australia, have yet to make pledges, but have stated they intend to. They are expected to announce contributions at COP.

If every developed country that has yet to pledge was to commit at least the same level as their previous contributions, it would bring the replenishment total to $12.5 billion. That’s not enough. Other rich, high-emitting countries, like COP28 hosts the United Arab Emirates, are under pressure to step up and pledge to the GCF. If they step up, they will be joining ten other emerging economies, including South Korea, Mexico, and Colombia, that have already contributed.

Keep track of all the GCF contribution announcements at NRDC’s Green Climate Fund Pledge Tracker.

Preparing for the post-2025 climate finance goal. During the 2015 summit that led to the Paris Agreement, governments also agreed on the need to set a new collective quantified goal for the post-2025 period. Countries agreed that the new goal will be “from a floor of $100 billion per year, taking into account the needs and priorities of developing countries.” Everything else was left up to negotiation. While a new goal is to be set at COP29 next year, countries are beginning to debate a number of questions, both technical and political. These include: the overall size of the new goal, the scope—what thematic areas and sectors should be covered, who the contributors are, the types of finance covered, how to track and account for progress, and how to ensure countries and communities can access the finance. Perhaps the thorniest question is which countries should contribute to the goal. With a growing number of other countries now having wealth and greenhouse gas emissions higher than many developed countries, a growing body of analytical work suggests that an equitable approach to climate finance goals would entail these additional countries also taking on responsibility to contribute. With only a year to go, COP28 needs to deliver a much clearer decision than COP27 managed, ideally starting to narrow options for what the final goal should look like.

Reforming the International Financial Institutions. Over the last 18 months, there has been renewed focus on how to reform international financial institutions, including the multilateral development banks, as well as the International Monetary Fund, to ensure they have the outlook and resources necessary to help countries tackle the climate crisis. At COP27, the outcome text includes several calls on multilateral development banks and their shareholders to make reforms. COP28 should build on this by setting out further action needed from MDBs and other international financial institutions. Read more about the key reforms to international financial institutions that NRDC and partners are calling for.

Protecting forests

Two years ago, at COP26, more than 140 countries signed the Glasgow Leaders' Declaration on Forests and Land Use, committing to halting and reversing worldwide deforestation and forest degradation by 2030. Unfortunately, in the nearly two years since, there have been significant warning signs that the Glasgow Declaration is not positioned to deliver on its promise, either in the tropics or in northern forests. In 2022, the loss of tropical primary forests increased, while degradation in northern forests continued essentially unabated, with devastating consequences for the climate and biodiversity. Longstanding policy inequities have allowed the Global North to call for action from tropical countries while sidestepping accountability for the significant impact of industrial logging in their own forests, which constitutes the single largest driver of tree cover loss in the world. Through carving out protections for their own industries, northern countries have hampered forest protection efforts everywhere. In August, the African Ministerial Conference on the Environment called on world leaders to adopt a Glasgow Declaration Accountability Framework (GDAF) "as a means of driving global progress and promoting greater equity between forest protection standards.” Since then, a growing contingent of policymakers, civil society organizations, and private sector leaders have supported the GDAF, which would drive transparency, facilitate policy and finance commitments, and foster alignment, positioning the international community to deliver transformative change.

Mobilizing action in northern forests. As part of the need to close accountability gaps on forest governance, developed countries need to show leadership on addressing the emissions associated with deforestation and forest degradation on their land, addressing loopholes that obfuscate the climate impact of industrial logging. A recent study estimates that logging, much of which occurs in northern forests, will contribute 3.5 to 4.2 billion metric tons of greenhouse gases to the atmosphere annually over the coming decades, an amount equivalent to approximately 10 percent of recent annual global emissions. In Canada, according to a report from NRDC and Nature Canada, the Government of Canada’s own data shows the country’s logging industry is responsible for more than 10% of Canada’s total annual greenhouse gas emissions. Each year, the logging industry clearcuts more than 550,000 hectares of forests in Canada, equivalent to six NHL hockey rink-sized areas every minute. The pace of these industrial logging operations has led Canada to lose its carbon-rich and biodiverse intact forests at a rate just behind that of Brazil. The integrity of Canada’s climate plan, as well as its commitment under the Glasgow Leaders’ Declaration on Forests and Land Use, depends on a full, accurate, and transparent accounting of all major sectors, including logging, and a strategy to reduce the logging industry’s emissions in alignment with its broader 2030 climate commitments.

Cleaning-up the commodity supply-chain. In addition to addressing their own domestic forest impacts, Global North countries need to develop standards curbing the impacts of their purchasing behavior on driving deforestation and degradation abroad. Countries should commit to eliminate their ‘imported deforestation and degradation’ by securing action from corporate leaders, using trade measures and procurement rules, and using other tools to halt global commodity-driven deforestation, degradation, and conversion while ensuring social and environmental safeguards.

Decarbonizing Industry

Reducing emissions from heavy industries such as cement, iron and steel, and aluminum is an emerging new component of the global architecture. At COP28 there will be new efforts to reduce emissions from the industrial sector.

Hydrogen. While offering a promising potential to support the energy transition by replacing fossil fuels in the hardest to electrify sectors of the economy, hydrogen also carries significant risks. If not carefully deployed and subject to rigorous guardrails, it risks hindering the clean energy transition and increasing its costs. Absent strong standards, hydrogen production can be very carbon intensive; and if hydrogen deployment is not targeted to hard-to-electrify applications, it can compete with more efficient clean energy solutions (notably, direct electrification) and stall the clean energy transition. So, enacting effective and rigorous guardrails is critical to harvest hydrogen’s best potential and minimize its risks. At COP28, it is essential that key decision-makers establish a robust global consensus for climate-aligned hydrogen deployment, and an agreement on the need for rigorous guardrails to enable this outcome. We need a race to the top for ambitious production standards across geographies including the US, EU, India and beyond, and agreement around where to prioritize hydrogen’s use to maximize rapid emissions reductions across the economy.

Delivering transformations in cement, steel, and aluminum. Industrial materials are foundational to everyday life and will be critical for the transition to a clean economy. However, the production of materials like cement, steel, and aluminum is highly emission intensive. In 2019, the industrial sector accounted for 24% of net global GHG emissions. Decarbonizing heavy industry will be key to aligning with the Paris Agreement goals. To be on a 1.5°C consistent pathway, by 2030 we need to halve the CO2 intensity of steel making and decrease the CO2 intensity of cement making by a third by 2030. Emissions reduction solutions for the industrial sector vary given the heterogeneity of industrial processes. Some decarbonization levers include: mitigation of process emissions such as reducing clinker content in cement; fuel switching and use of alternative feedstocks (such as green hydrogen); electrification of currently non-electrified industrial processes; and clean power and energy efficiency. demonstration, and deployment for transformative technology will be key to addressing these important sectors.

Critical to this work is ensuring an equitable transition that prioritizes frontline communities worldwide. While we work to reduce our global GHG emissions through industrial decarbonization, we must ensure these approaches account for local air quality impacts such as reduction in criteria air pollutants including SOx, NOx, and PM2.5. Protecting frontline communities locally, and globally, from air pollution, is paramount to an equitable transition and achieving our climate goals.

As many industrial materials are traded on global markets, global trade measures will play a large role in creating a level playing field for lower carbon technology. As one example, the US and EU continue to negotiate on a “Global Arrangement on Sustainable Steel and Aluminum (GASSA)”. Equity considerations should also be at the forefront of industrial trade agreements, with a particular focus on fairness for Least Developed Countries (LDCs). At COP28, key companies, investors, and countries should commit to coordination and action to decarbonize the cement, steel, and aluminum sectors.

More emissions cutting action

To deliver on the promise of the Paris Agreement—to pursue efforts “to limit the temperature increase to 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels”— countries, companies, investors, and decision-makers will need to deliver greater action across all key sectors of the economy.

Delivering on the Promise of Paris by 2030. At COP28, we will need to see a series of new commitments and actions to close the emissions gap by 2030. These commitments will be reflected in the negotiated Global Stocktake response, enhanced political commitments, and new coalitions. The results of various studies are clear: delivering a set of concrete actions right now can put the global of 1.5°C goal within reach.

Setting the Conditions for the 2035 NDCs. The G20 countries signaled their intent to have their 2035 climate targets—their next NDCs—be economy-wide, with all emissions. This commitment was further solidified when the US and China agreed that “both countries’ 2035 NDCs will be economy-wide, include all greenhouse gases, and reflect the reductions aligned with the Paris temperature goal…” and signaled intent to ensure that the COP28 outcome includes this economy-wide target framework for all countries. At COP28, countries should commit to have economy-wide 2035 targets by solidifying that in the Global Stocktake decision.

Climate ambition and action: The clock is ticking

Everyone meeting at COP28 in Dubai has a responsibility to deliver more ambition, accountability, and equity in the global response to climate change. Leaders can do this by:

- decisively responding to the fact that we are off track

- mobilizing additional actions that they will deliver this decade

- committing to phase-out fossil fuels in a rapid and equitable manner, enabled by a tripling of renewable energy capacity by 2030, a doubling of energy efficiency by 2030, a decline in coal, and a more rapid transition in oil and gas

- delivering stepped up finance for climate mitigation, adaptation, and loss and damage to accelerate the transition and help the poorest cope with the impacts of a crisis which they have contributed little to

- ensuring countries deliver action across the entirety of their economy and all greenhouse gases.

All of us must commit to do big things—right now—while we still can.